Henry Cowell Talks Modern Music on the Masterwork Hour

We don't hear the pieces themselves but do get Cowell's illuminating and very personal descriptions of each work. He starts off talking about his own Hymning and Fuguing Tunes Nos. 2 & 5, describing a period in Boston in the late 18th century when hymn and anthem writers, cut off from England, came up with their own, uniquely American idiom that was "considered crude but had a tremendous strength and vitality." His extension of these forms asks the question, "What if America had adopted this style rather than that of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven?"

Then he introduces a Sinfonietta by Dane Rudhyer, describing the ex-student of Debussy's interest in Oriental philosophy. "It should all sound like one giant gong," he reports the composer saying. Henry Brant's Saxophone Concerto is next. Brant has "a Puck-like imagination and humor" when it comes to instrumentation. He is also "the world's best player on the tin whistle." Peggy Glanville-Hicks' Three Gymnopedies show her "well-tailored simplicity" which is not to be confused with naiveté. Though Australian, she is "a citizen of the world," as the very French-sounding piece illustrates. Finally, Cowell describes his own Symphony No. 11, in which each movement reflects "a use that is involved in music," a lullaby, a work song, etc. Cowell was a relentless advocate of modern music These generous and informative introductions attest to that.

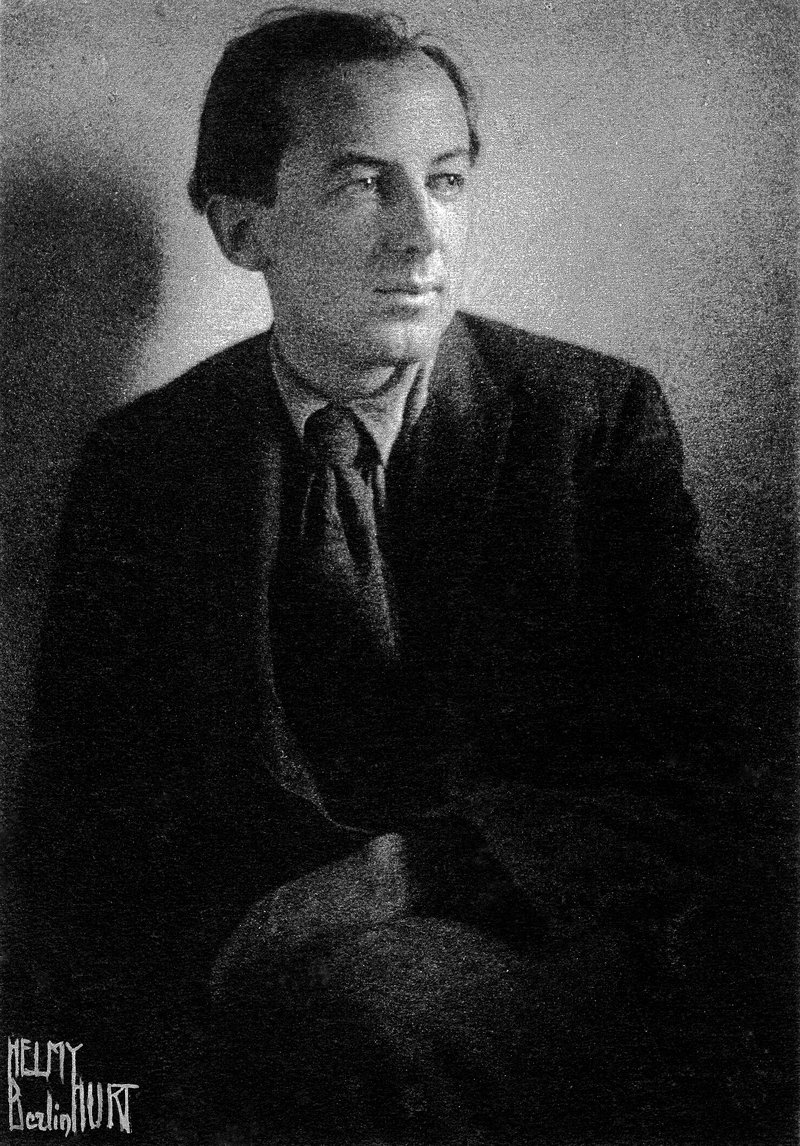

Henry Cowell (1897-1965) did not take the normal route to a career in composition. Born poor and on the West Coast, his musical upbringing exposed him to influences most musicians of the time never encountered. The Wall Street Journal tells how:

Living in San Francisco, the young Cowell and his mother couldn't afford to attend European operas, so they sat outside the city's Chinese-opera houses and listened to music few Westerners knew. Cowell regarded non-Western music as equally worthy of attention as European classical music, then a radical philosophy for an American musician, and in the 1920s staged some of the first concerts of non-Western music by non-Western performers on both coasts.

But Cowell's work was more than just an exercise in assimilating exotic traditions. He was one of those true, stubbornly self-taught American "primitives," unwilling to accept the conventional musical givens of the day. The Encyclopedia Britannica notes how:

…seeking new sonorities, he developed “tone clusters,” chords that on the piano are produced by simultaneously depressing several adjacent keys (e.g., with the forearm). Later he called these sonorities secondal harmonies—i.e., harmonies based on the interval of a second in contrast to the traditional basis of a third. These secondal harmonies appear in his early piano pieces, such as The Tides of Manaunaun (1912); in his Piano Concerto (1930); and in his Synchrony (1931) for orchestra and trumpet solo. Some of his other piano compositions, such as Aeolian Harp (1923) and The Banshee (1925), are played directly on the piano strings, which are rubbed, plucked, struck, or otherwise sounded by the hands or by an object. Cowell’s Mosaic Quartet (1935) was an experiment with musical form; the performers are given blocks of music to arrange in any desired order. With the Russian engineer Leon Theremin, Cowell built the Rhythmicon, an electronic instrument that could produce 16 different simultaneous rhythms, and he composed Rhythmicana (1931; first performed 1971), a work specifically written for the instrument.

Cowell has a separate place in history as a victim of the harsh penalties given to people engaging in homosexual activities. Convicted in 1936 of having consensual sex with a 17-year-old male, Cowell was sentenced to fifteen years in prison. He served four years at San Quentin, where he taught inmates, started a prison band, and wrote over sixty compositions before being pardoned. His musical output after being released is more conservative, based on historical and folk antecedents rather than the more avant-garde explorations described above. Whether or not that is a result of his incarceration is a subject of debate. Cowell's life, full of incident, of highs and lows, of astounding artistic production and radical innovation, still fascinates. The Juilliard Journal tries to sum him up:

Musical pioneer. Prolific composer. Piano virtuoso. Tireless proponent of new music. Globe-trotter. World-music advocate. Convicted felon. As Juilliard faculty member Joel Sachs said in a recent interview… “The problem with Henry Cowell is that if you had invented his life, no one would believe it.”

Audio courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives WNYC Collection.

WNYC archives id: 150168

Municipal archives id: LT6770