The Brian Lehrer Show

The Brian Lehrer Show

The History Behind the New Movie 'Oppenheimer'

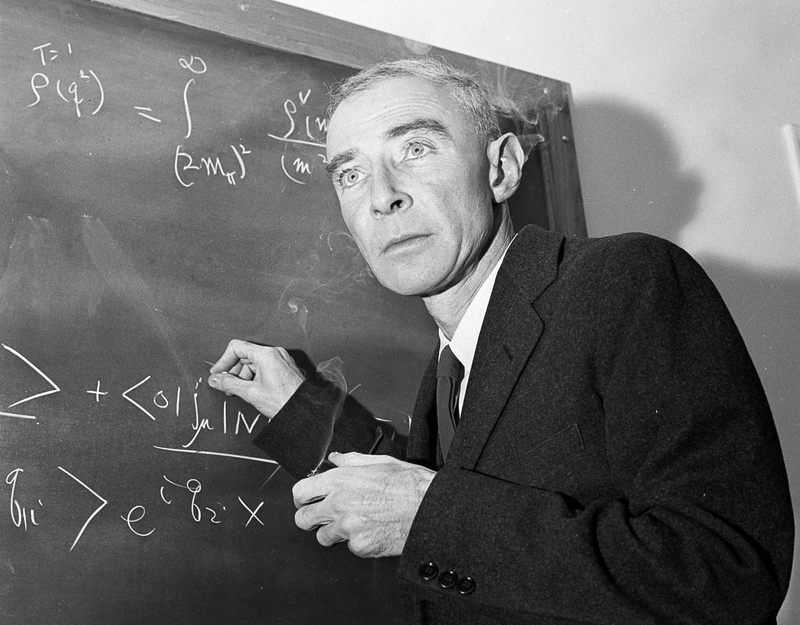

( John Rooney / AP Photo )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone. Now, a very informed take on the history behind the movie, Oppenheimer. Fred Kaplan, military affairs columnist for Slate, has written two books on the subject, The Wizards of Armageddon, which came out in the '80s, and his much more recent 2021 book, The Bomb: Presidents, Generals, and the Secret History of Nuclear War, for which he was on the show for a book interview.

Now, he's also written a kind of historical fact-check article/movie review about Oppenheimer on Slate. Spoiler alert. He says most of it, including some parts that might seem unreal, are real. By the way, Fred also has a much shorter piece about the geopolitical implications of the Barbie movie, believe it or not, so we'll touch on that too. Fred, always good to have you on. Welcome back to WNYC.

Fred Kaplan: Anytime.

Brian Lehrer: You write, the film, Oppenheimer, is a mind-blower both for director Christopher Nolan's artistic innovations and also because of the story itself. Can you actually start just briefly for people like me who haven't seen it yet by saying what you mean by artistic innovations? What's new visually in this film to your eye?

Fred Kaplan: Well, this film, above all, it's an immersive exploration of what it's like to be Robert Oppenheimer. He's thinking about completely new concepts in physics and their implications in the real world. There are these visual flashes that illustrate this. Surprisingly, it's convincing. There's a scene toward the end of the film where he's giving a speech to his fellow scientists after the Hiroshima bomb congratulating everybody for succeeding, and yet things are zapping through his head horrible images that illustrate his ambivalence about the bomb.

Now, I don't know, nobody knows whether he was feeling ambivalent at that moment, but we do know that both before, during, and after, he had tremendous ambivalence about the bomb. I think this was just a brilliant visualization of this psychological phenomenon. That's what I mean. I think it was really, given all that's packed into this film-- and I've seen it twice. The first time, I spent too much time worrying about whether people who weren't familiar with this history are really going to be following any of this, but I think he actually got away with it. I think it's, in a narrative and artistic sense, a pretty brilliant feat.

Brian Lehrer: On it as an immersive, visual experience of being Robert Oppenheimer as you describe it, there's all this talk now, "Should I see it in an IMAX, see it in 70mm?" I see the tickets at those kinds of theaters are being sold out way in advance of regular screens. Locally, what kind of screen did you see it on?

Fred Kaplan: The first time I saw it was at a screening with a panel. It was in a movie theater in a hotel and it was in digital cinema projection. It was just high-definition. It was okay. Then the second time I saw it was at a screening at the IMAX 70mm theater on the Upper West Side. The picture was much better. One thing, the sound-- and I don't know if it was at that theater or just where we were sitting, but the dialogue was sometimes hard to make out.

I've been to some other Nolan film on an IMAX screen where the bass was turned up way too high. Apparently, his direction. I don't know. I've heard other people who had no problems at that theater hearing anything. I would say at least see it in 70mm if not in 70mm IMAX. 70mm film is such a wonderful medium. There are so few theaters that even have the capability and there are a few in New York. I think it's even worth the wait to see it at least in 70mm or 70mm IMAX.

Brian Lehrer: There you go. You're right that the film is mostly a faithful portrait, especially perhaps in the scenes that some might assume are made up or exaggerated. Can you give us an example of one of those?

Fred Kaplan: Well, for example, it starts out with Oppenheimer as a grad student in England, where he's going crazy. At one point, he gets really angry at his professor, who is very notable physicist named PMS Blackett, and injects poison into his apple. He takes it away before the professor has a chance to eat it. Certainly, that has to be exaggerated. Well, no, apparently, there are a few sources indicating that that really did happen. That's the one that I know when I told people they were most surprised that it was true. It's also true in one scene. He's about to give a lecture on physics, the new physics to an audience in the Netherlands and starts speaking in quite fluent Dutch.

Apparently, he really did teach himself Dutch over a period of a few weeks before giving this lecture. He was almost outer-space spooky, brilliant about-- He's talking with a communist at one point who's correcting whether Marx talked about property or ownership. Oppenheimer says, "Oh, well, I read it. All three volumes of capital in the original German." He was quite fluent and well-studied in literature, philosophy, and history, in English, French, German. He was teaching himself Sanskrit, which is where that phrase, "I am become death, destroyer of worlds," comes from.

Brian Lehrer: Explain that. That's a quote from the Bhagavad Gita, right?

Fred Kaplan: Well, he said later that when the bomb went off, he thought of a phrase from the Bhagavad Gita, "I am become death, destroyer of worlds," which sounds pretentious, and I guess it is. Other reports say that basically when it happened, he said, "It works." [chuckles] He was teaching himself how to read Sanskrit and apparently had read the Bhagavad Gita. The actor who plays him, it's a remarkable portrayal.

If you look at photographs or film footage of the time of Oppenheimer, he was bone thin, had this lanky demeanor and this off-centered gait, and had these spectral, wide blue eyes. He really does look and act quite a lot like him. It's remarkable. Apparently, Kai Bird, who wrote the biography, was on the set. When the actor came over to him to introduce himself, Kai said, "It's good to meet you, Dr. Oppenheimer. I've been waiting to talk with you for decades."

Brian Lehrer: [laughs] All praise to the art of acting as well as the art of being a nuclear physicist. Yes, of course, the movie is based on that book. Listeners, your questions for Fred Kaplan, author of books about the history of nuclear war on the historical accuracy of the movie, Oppenheimer, or the artistic immersion experience of it. 213-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692.

Your calls or texts. Yes, we will get to a short Barbie addendum in the geopolitical context that Fred also wrote about at the end of the segment. You portray Oppenheimer as insistent on his independence as a scientist with all that brilliance, but also pliant in his role as a mere adviser to authority as you put it. Can you give us an example of how those attitudes came into conflict for him?

Fred Kaplan: Well, this was a very new thing, a team of hundreds of mainly theoretical physicists doing a project for the US military, building a bomb. Isidor Rabi, who was a good friend of Oppenheimer, and Oppenheimer asked him to join the project, and Rabi didn't want to do it. He saw the point, but he says, "I don't want the climax of 300 years of physics to be the destruction of a bomb that can kill hundreds of thousands of people."

At the time when the Manhattan Project was set up, which was what they called was the codename for this project to build an atomic bomb, there were reports that the Germans were working on a bomb. They had brilliant physicists. It was thought that, "Well, if the Germans beat us to the bomb, they're going to use it, and we're going to lose World War II." The initial impetus was that was the motive.

Then in 1945, the Germans surrender. There were many people, including some scientists, who said, "Well, look, the Japanese don't have-- They're not working on a bomb. We're done. We shouldn't use this as a weapon." Oppenheimer's position at the time and after was, "Look, this is not our decision to make as scientists. Besides, what do you guys know about Japan?" There was some intelligence, and this is still a matter of some dispute among historians, that the Japanese were never going to surrender.

The high command of the Japanese military, and especially their junior officers, they were willing to fight to the last man. We were planning an invasion in November and tens of thousands of Americans would be killed. If you're the president or anybody else at the time and you're thinking, "Well, here, I have this huge weapon, which actually might end the war. If I don't use it and if 50,000 Americans are killed invading the mainland, this is not going to be good."

Oppenheimer bought onto that argument. He also thought that this weapon might be so destructive that it might deter people from fighting the wars in the future, but you have to use it to show people how horrifying it is and so we didn't use it. The next war certainly would use the weapons. Because people didn't know how powerful it was, they could sleepwalk into total armageddon.

Brian Lehrer: Even further to that point, you in your article have Oppenheimer in conflict with another nuclear scientist on whether to drop the bomb first on somewhere unpopulated to show the Japanese leadership its power and hope they surrender just based on that, but no, Oppenheimer wanted to just go ahead and bomb Hiroshima. Why?

Fred Kaplan: Well, it was Leo Szilard, who had been one of the scientists, along with Albert Einstein, to write a letter to President Roosevelt in 1939, warning about the Germans working on a bomb. Szilard organized this petition, saying, "Look, let's not drop this on a city. Let's have the Japanese witness a demonstration, say, on an unpopulated island or something."

Oppenheimer's point, and this was other people's point too, was like, "Look, viewed from a distance, it might not look that horrible. Second, what if it's a dud? What if it doesn't go off? Then it's going to be worse than nothing because then you blow up a city and the Japanese might think, 'Well, that one worked, but the first one didn't, so we'll hold out longer,' and then you might have to use three or four or more." Two bombs were dropped.

One thing about the decision to drop the bomb, and this is important, and the film doesn't quite bring this out, there was never really any controversy in the higher councils of government whether to drop this bomb on Japan. The bomb became ready, then it was dropped. A second bomb was ready and it was dropped. A third bomb was going to be ready a few weeks later, but Japan surrendered. If they had not surrendered by that time, it would have been dropped. It was, by this point, an automatic process.

If you think about it, to many people, we didn't know a lot about it. Nobody knew anything about this weapon at the time. It was a top-secret project. Truman didn't know about it until 10 days after he became president when he was finally briefed about it. You think, "Okay, we have this powerful weapon. We've been in this horrible war, this savage war, the war into the Pacific especially, just a savage war. Here's this new weapon. It might end it. What is the argument against using this?" I'm saying this from the point of view at the time.

Brian Lehrer: Right.

Fred Kaplan: There was never really a decision to drop the bomb.

Brian Lehrer: What about after they bombed Hiroshima and saw the unbelievable human toll? They still went ahead and dropped the second bomb on Nagasaki.

Fred Kaplan: Well, again, it was ready three days later. There's still tremendous controversy over whether that was necessary. I think a case can be made that it might not have been. Three days had passed. The Japanese probably hadn't even had time to contemplate the consequences. There's a cliché, "Well, we needed to drop the first bomb to show that it worked. We needed to drop the second bomb to show that we had more than one." Well, maybe, but that's not proved. Again, it was a weapon. We were in a war. Here, we dropped the one when it was ready. We dropped the second one when it was ready.

Brian Lehrer: You also write in your article about the movie that it's accurate as shown in the film that President Truman, after dropping the two bombs on Japan, called Oppenheimer a crybaby for feeling bad about it. What was the context of that?

Fred Kaplan: Well, Oppenheimer comes in for a meeting with Truman. Truman wants to congratulate him. This was after Hiroshima and Nagasaki. What Oppenheimer wants to talk about is the need to establish arms control talks, that Russia is definitely going to get this bomb too, and we need to put it under some control. Truman says, "I don't think the Russians will ever get this bomb." That's true. He did say that. Then at one point, Oppenheimer says, "I feel I have blood on my hands," which was probably not the wisest thing for someone in his position to say.

The report is that Truman takes a handkerchief out of his pocket. There are two versions of this story. One is he takes a handkerchief out of his pocket and hands it to Oppenheimer. The other, he says, "Look, if anybody, I have blood on my hands. Leave it to me." In the movie, he just takes out a handkerchief. Then Oppenheimer, as he's leaving the room, you hear Truman say, "I don't want that crybaby in here ever again." Well, he did say that later. He didn't say it with an earshot of Oppenheimer, but he did say that to, I think, Secretary of State Byrnes after the meeting.

Brian Lehrer: We're going to take some phone calls now for Fred Kaplan, who has written two books about nuclear war and nuclear weapons, The Wizards of Armageddon, and The Bomb: Presidents, Generals, and the Secret History of Nuclear War. We're getting his take with that background that he has on the movie, Oppenheimer. By the way, Fred, I never told you this, but I read The Wizards of Armageddon about five years before I came to work here. That's the kind of geek I am. When I first met Brooke Gladstone here at WNYC and learned you are her spouse, I thought, "She knows Fred Kaplan from The Wizards of Armageddon?"

Fred Kaplan: Now, people say, "You know Brooke Gladstone?"

Brian Lehrer: Exactly, but that's how much of a geek I was even before starting this geeky job. Okay, let's take a phone call. Mia, a professor at The New School in New Jersey, you're on WNYC. Hi, Mia.

Mia: Hi, Brian. Love your show. Hello, Mr. Kaplan. I guess my comment is this whole, just incredible society-wide adoration of Oppenheimer now with this film. It's really rubbing me the wrong way. Yes, I'm Black and Korean, so I'm aware of the violence of this period on the Japanese people, but it just seems like a giant moral failing. It seems like this sycophantic adoration of Oppenheimer. Yes, he was smart. There are plenty of smart people who do incredibly evil things. Yes, they're brilliant, they're genius, but should they really be celebrated? Mr. Kaplan a minute ago said, he said it's not the wisest thing to say regarding blood on his hands. What do you mean? [chuckles]

Fred Kaplan: Quite influence--

Mia: That's not the wisest thing. It's a moral failure to even say something like that. Imagine the grandchildren-

Fred Kaplan: Let me ask you. Have you seen the film?

Mia: -of those people are listening to this show right now. Imagine the casual disregard they would experience.

Fred Kaplan: Have you seen the film?

Mia: No, I haven't seen the film. I'm not planning on seeing--

Fred Kaplan: Well, I think if you did--

Brian Lehrer: Hang on, hang on. One at a time. Mia, go ahead.

Mia: I've seen clips of the film. I've read a zillion reviews of the film. I've listened to way too many clips like this. It's this adoration of the single brilliant white dude instead of the incredible violence that was wrought. This is real intergenerational harm that is being celebrated.

Fred Kaplan: I think if you saw the film, you would see that it is not an adoration of Oppenheimer. It's a portrait--

Mia: Really? Are the victims of this violence centered in this story or are they just anecdotally mentioned?

Fred Kaplan: No, there's one scene. Some people have said, "Gee, they should have shown some footage of Japanese," but there is--

Brian Lehrer: Well, they're not centered, right? That would be a fact, right? They're not centered.

Fred Kaplan: That would be a different film.

Brian Lehrer: Yes.

Fred Kaplan: There are two things--

Mia: I think if we have some moral-

Fred Kaplan: No, excuse me. Excuse me.

Mia: -responsibilities in the year 2023--

Brian Lehrer: Go ahead, Mia. Finish your thought.

Fred Kaplan: I think [unintelligible 00:19:55] this film are aware of the horrors of the nuclear bomb. This film also shows Oppenheimer. It's not a kind of film where there is anything like spoilers. He is talking with Einstein about the possibility that by unleashing this thing, they have created a situation where someday, the world might be destroyed. There is one scene where Oppenheimer is watching film footage of Hiroshima. I think this was actually a more dramatically potent way to handle it. Oppenheimer is looking away. He can't look at the film. He doesn't want to face the consequences of his actions.

Actually, one thing that actually surprised me, it is not hagiography. It is, as I said, a portrait of a tormented, deeply ambivalent, and tragic figure. While it's true and people have complained about this, it doesn't talk about the radioactive fallout from the nuclear test in New Mexico, except for a couple of very fast flashes. It doesn't portray the damage of Hiroshima. It certainly does portray layout dramatically, although mainly in people talking about it, the horrifying consequences of this. It's not the kind of film you want and that's a legitimate position, but it certainly does not minimize or sweep away the angle that you're talking about.

Brian Lehrer: Mia, thank you for-- I'm sorry. Go ahead.

Fred Kaplan: Nor does it paint Oppenheimer as some kind of hero. It's a very complex story. If it had portrayed the things that you wanted portrayed explicitly, and I completely understand your position, it would've been a very different film. For the points that you wanted to make, I think it makes the most points in other equally dramatic ways.

Brian Lehrer: Mia, thank you very much for raising that important question. I'm going to go next to another caller who has a personal connection to some of this history, I think. Larry in Forest Hills, you're on WNYC. Hi, Larry.

Larry: Hi, Brian. Hi, this is my third call in here. This one, my father fought in the Philippines. After the bomb was dropped in Nagasaki about a month later, they sent occupation forces, at least the one my father was in. There were hundreds of thousands of people running around into Japan. My father sat in the dirt, ate the food, drank the water. I have a million pictures.

He was dead at 36 from lung cancer. I've been sick my whole life. My sister was born with a hole in her heart and she had Bell's palsy at 18 months, which doesn't happen. I'm active in groups, Children of Atomic Vets, the National Association of Atomic Vets. There's a bunch of different people whose parents were radiated during the war and, of course, atomic testing. Mostly atomic testing because the people from the war generally all died.

The government said, "No, we're sorry. We didn't do that." My mother was able to collect Social Security but not war benefits as a war death. As I said, my father was dead at 36. They were not allowed to tell anybody, including their doctors during testing, et cetera. I have not seen the film. I may go see the film. I read about this stuff every day because I'm involved with-- This is generational.

This gets handed down. I have kids. Hopefully, one day, I'll have grandkids. My kids may suffer from this. I understand why he made the film. I understand talking about this guy. He was brilliant, et cetera. People in my atomic vets [unintelligible 00:24:26], some have gone to see the film with a rather large photo of their departed loved ones due to the bomb. That's all I have to say.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you.

Fred Kaplan: I think that's a proper protest. Also, I will say this. Quite apart from issues about this film is that the US government has engaged in rather appalling minimization of the damage from radiation and radioactive fallout from the beginning. Now, before the bombs were dropped, there was no idea how far the extent of radioactive fallout would linger or how long its effects would last once soil was affected.

It certainly was known soon after partly from the teams that the caller's father and other people went on. They covered it up. Now, this affects not only the damage done by people like the caller's father and perhaps her own children but also in analyzing the effects of nuclear weapons. For example, in coming up with calculations of how many weapons you need to do certain amounts of damage in a war, they have only looked at blasts.

There's blast, there's fire, there's radiation, there's radioactive fallout. Fire, smoke, and radioactive fallout have vaster damage than blasts. They have only calculated blast. They say, "Well, the other effects, it depends on the wind, it depends on the weather, it depends on the height of burst of the bomb, and so forth, whereas blast has pretty precise effects." What this does, it has led to an overestimate of how many weapons you need to do certain kinds of damage.

In many ways, both in terms of human and in terms of policy, the coverup of radiation, and now things like nuclear winter whereby some calculations of 80 nuclear bombs went off in a particular place, it might mean the end of life on Earth. Most war plans call for a lot more than using 80 weapons. Should this film be condemned for not going into all of this? Well, I don't know.

It would've been a completely different film. Maybe one might hope. Nobody has talked about nuclear weapons much lately. Maybe this will lead to a revival of interest. I know that Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin's book, American Prometheus, that this movie is based on, it came out in 2004. It was never a bestseller. It is now number three on the paperback bestseller list.

Brian Lehrer: Huh, so people are reading about--

Fred Kaplan: People are going back and looking at this. Maybe the film will revive interest in precisely the kinds of issues that both of the callers have been raising and I hope that that's the case.

Brian Lehrer: I was thinking about how this isn't the kind of topic we might think would generate the blockbuster buzz and ticket sales to put it alongside something like a Barbie, this kind of serious historical film about one of the most serious things in human history. Why do you think it is? Do you think it's mostly because it's Christopher Nolan, who people associate with the Batman movies and things like that, and it's that simple?

Fred Kaplan: I don't know. I do think that the PR people who dreamed up this whole Barbie-Heimer thing-- I don't know, Brian. If you ever want to publicize something, find out who came up with that and hire that person no matter what it costs. The idea that people are actually going to double features of Barbie and Oppenheimer because everybody's doing it, it's just mind-blowing. I think it will be studied by business departments all over for years or decades to come.

Brian Lehrer: That leads us to the Barbie addendum to this Oppenheimer conversation that I told everybody was coming. You have a much shorter article on Slate about the Barbie movie in which you inform us, for example, that the film is banned in Vietnam. I thought, "Which of these movies would I have guessed that Vietnam banned? The one about the US government that bombed the hell out of their country or the one about a toy?" It's the one about a toy. Tell us why.

Fred Kaplan: Well, there is a scene in Barbie. I haven't seen the movie yet. I plan to, but I've seen the still photo that this is referring to. It lasts a matter of seconds. Barbie is looking at a map of the world and it's not a real map of the world. In the middle of this map, in the middle of an ocean are some dashed lines. People in Asia looked at that and said, "Oh, my God, that is the nine-dash line."

The nine-dash line is a line that the People's Republic of China has drawn in its official maps of the South China Sea demarking what they see as China's actual border. This border is disputed by almost every other country. There have been little wars with Vietnam over the location of this line. Vietnam took this as an acceptance, an acknowledgment of the Chinese border.

Ted Cruz called the movie a piece of Chinese communist propaganda. Well, Warner Bros. said, "Look, this is nuts. This is an imaginary map. China really isn't even on the map. There are eight dashes, not nine anyway." As some person told me, he goes, "Look, it's a little disingenuous." There's a big China market for Hollywood. There are not very many films made in the last 20 years where China is the bad guy or there is a war with China, and that's to protect the China market.

Warner Bros. is having it both ways. Somebody told me and put it, "Well, why put little dashed lines on a map anyway?" It's clearly somewhat, obliquely, a reference to satisfy China to make it look like there's the nine-dash line, but there's also a way of covering their butts by saying, "There's no real China on this map anyway and it's only eight lines." Again, this has caused a crazy, big storm that is, in part, ludicrous and, in part, an illustration of the extent to which Hollywood still relies a lot on China for its business.

Brian Lehrer: There we leave it with Fred Kaplan, military affairs columnist for Slate, who has written two books on the subject of nuclear war, nuclear weapons. The Wizards of Armageddon, which came out in the '80s, and his 2021 book, The Bomb: Presidents, Generals, and the Secret History of Nuclear War. Fred, thanks so much for coming on and sharing your impressions of Oppenheimer and taking calls.

Fred Kaplan: All right, thank you.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.