The Brian Lehrer Show

The Brian Lehrer Show

Rikers in Crisis: A Rare Visit From the Mayor, What Role Judges Play

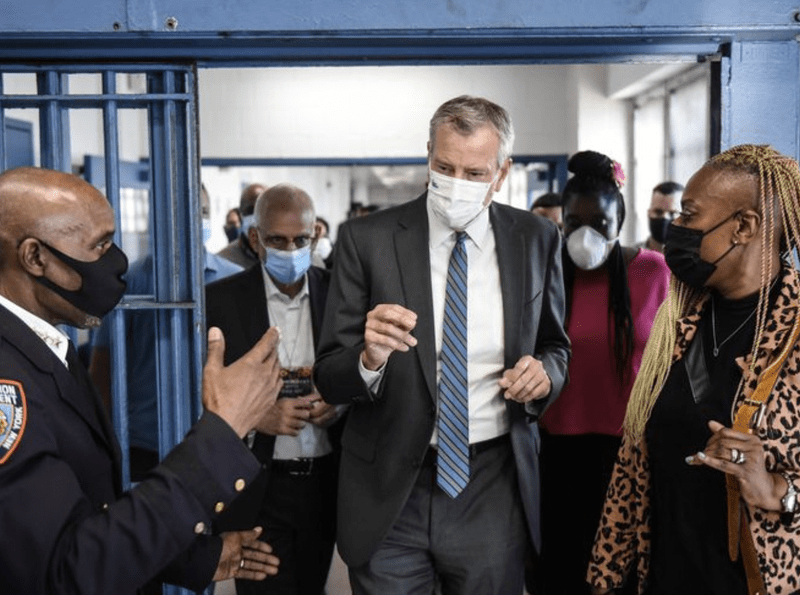

Mayor de Blasio visited Rikers Island Monday in his first trip since 2017. Jake Offenhartz, Gothamist/WNYC reporter, was there, and reports on what the mayor saw and said about the ongoing crisis.

Then, while Governor Hochul has signed legislation to release a couple of hundred detainees on Rikers Island amid the escalating crisis, New York City judges continue to set bail and send more people to jail. George Joseph, reporter with WNYC’s Race and Justice Unit and Akash Mehta, editor-in-chief of New York Focus, talk about their investigation into what criteria judges use to set bail, and which judges do it the most.

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, everyone. If Mayor de Blasio saw anything disturbing on his visit to Rikers Island yesterday, he doesn't seem to want us to know what it was. We'll play some clips in just a second but remember the context. After 12 deaths this year at the jail complex, and with so many correction officers pretending to be sick and not showing up for work, and after the court-appointed federal monitor saw a guard not intervening when someone was trying to hang himself. After 42-year-old Isaabdul Karim caught COVID from overcrowded conditions, not the usual spacing between inmates in pandemic times, and he died from it last week.

After a records check by New York Focus found inmates not being able to keep thousands of medical appointments. After all the Democrats in New York City's congressional delegation wrote a letter to President Biden last week basically asking for the feds to run the place for a while because the city apparently can't. After members of the state legislature visited the jail, and after three DAs and the state attorney general visited last week and described what they saw, and after de Blasio ally, Eric Adams, likely next mayor, added his voice to the cause for de Blasio to visit, the mayor finally went to see something there for himself for the first time in four years. That was yesterday.

The thing is, though, when he took questions from reporters afterwards and when he made a statement, he wouldn't say what it was he saw. Let's take another step back. The mayor had been resisting calls to visit the island himself saying he could learn everything he needed to know about it by getting reports from his deputies. On this program last Friday, when I asked him about Eric Adams now also said he should go, the mayor was ready to make an announcement.

Mayor de Blasio: Next week, I'll go visit. I think it's time because we've been able to address a number of issues and I want to see if these solutions are working or whatever other things we have to do.

Brian Lehrer: Not to see how bad things were, but to see how things were getting better. That was Friday. Yesterday, he went. Afterwards, a reporter asked if he was upset by what he saw, and the mayor said.

Mayor de Blasio: I was upset when I took office. I was upset four years ago. I remain upset. This is a place that should have been shut down a long, long time ago.

Brian Lehrer: That's very general. A reporter followed up asking, what was the most specific upsetting thing that he saw? Is it a place where you would have your own child?

Reporter: What was the most upsetting thing you saw today and [unintelligible 00:02:49] your own child be here? Is this a place where you would have your own child be [unintelligible 00:02:54]?

Mayor de Blasio: Look, every parent does not want to see their child end up in incarceration to begin with, obviously.

Brian Lehrer: Obviously, but no specifics about what he saw. That was different from Brooklyn DA, Eric Gonzalez, for example, who came on the show last week after his tour and described things that upset him. For example.

Eric Gonzalez: We were in a men's prison. We saw a lot of men who were put into very crowded cells when they were waiting for intake onto the island, meaning the process of getting them screened and put onto the island. They're waiting there and they're being quarantined in place under conditions that are heartbreaking.

Brian Lehrer: Brooklyn DA, Eric Gonzalez here last week. With us now, WNYC and Gothamist reporter, Jake Offenhartz, who covered the mayor's trip to Rikers yesterday. Hi, Jake.

Jake Offenhartz: Hi, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: What was the scene around this visit yesterday and who was with the mayor?

Jake Offenhartz: The mayor had some of his top aides with him. Vincent Schiraldi, the corrections commissioner with him. He gathered all of us on the island in the commissioner's office, which I believe is a former church in this very tiny room on pretty short notice, and watched into this very euphemistic avoided public statement. I think you just summarized it.

He went on this tour that so many officials have done this procession of, Democrats and Republicans have done as things have spiraled in recent weeks. They all reported nightmarish conditions, just awful, really harrowing things. The mayor comes out here and he says Rikers is broken, he wants the jail closed in five years, but he also refuses to say that anything he saw was upsetting to him and he doesn't want to go into detail. He says his mission is to talk about things that are going well.

At the same time, his correction commissioner, Vin Schiraldi is acknowledging that things are not going well. He's a little blunter than the mayor. It set up this very strange public-facing statement that I think reporters were pretty surprised by. I imagined the public was too. I think the other thing to note here is that the mayor did not talk to anyone detained at Rikers. He did not talk to any rank and file correction officers. He said that that was not part of his mission yesterday.

Brian Lehrer: You upstaged me. Let me back up one step and play a clip, one more clip of the mayor that I was going to play. Let's go a little deeper into what you just said because the mayor was asked why he didn't take any journalists on the tour to observe conditions with him or see whether he was being shown the real stuff or if the Rikers' leadership was trying to whitewash anything. Here's why he said no journalists.

Mayor de Blasio: Because this was an opportunity to go and see exactly what work was being done. Look, I respect the role that journalists have to play. This was an official tour to see the work and have the conversations with the people doing the work.

Brian Lehrer: Have the conversations with the people doing the work, but you just told me he didn't speak with any correction officers. He didn't?

Jake Offenhartz: No. I think he may have spoken with a healthcare worker, maybe more than one healthcare worker. He really just didn't go into detail here. We do know that he visited two facilities, the Eric Taylor Center and the Otis Bantum Correctional Center. Otis has been one of the more notorious facilities in recent years, saw the death of 25-year-old Brandan Rodriguez last month. The mayor also visited an intake center, another site with a lot of controversy and scrutiny where a different man who you mentioned, Isaabdul Karim, he was incarcerated on a technical parole violation. He died after being held there for 10 days without access to food or medication according to his lawyers.

We are told by the mayor that those problems have been solved. He brought in more personnel and there's more space. His critics are saying no, actually, they just cleared it out for the mayor's visit. The paint was still fresh according to the head of the corrections guard union. The implication here is that the mayor got a sugarcoated tour. He was walking around as if he was blindfolded almost without talking to the people most affected.

Brian Lehrer: Do you know who gave him the tour?

Jake Offenhartz: I guess it was Schiraldi, is my sense. Again, it's hard to know exactly what he saw.

Brian Lehrer: Vin Schiraldi, the correction commissioner. He has a history as an activist in this before de Blasio appointed him earlier this year as the new correction commissioner. The reviews on Schiraldi I think have been good and he doesn't seem like somebody who would want to whitewash conditions as opposed to show the mayor, "Look, look at this, look at this," or am I wrong?

Jake Offenhartz: I think that's a good question. I do think that he absolutely has a reputation as a reformer. During this press conference after, I think was actually a little bit more straightforward about the problems than the mayor was. He acknowledged that these triple shifts, this big point of contention with the union, that correction guards are working are not over, they are going to be gradually reduced. Currently, people detained at Rikers can't have outside recreation, because there's not enough staff, but they have some in-unit programming.

He was the one who was, I think, willing to say this is absolutely not where we want to be where the mayor's focus was very much we are addressing these problems, things are improving, there's a real impact of our recent measures. The context for that is that he is fending off threats of federal intervention here. That's something he doesn't want as he said on the show last Friday.

Brian Lehrer: Just one more thing before you go to give some credit if credit is due, the headline of your article on Gothamist about the visit says de Blasio defends real impact of the city's crisis intervention and the issue that DA Gonzalez cited in the clip that we played. We think that's how Isaabdul Karim caught his fatal case of COVID days spent in the overcrowded intake area. That seemed better?

Jake Offenhartz: We were told that was better by the mayor. Other people say that they cleared it out ahead of his visit. I think we will need to be in touch with both correction officers and public defenders in the coming days just to see how much this sticks.

Brian Lehrer: Did the mayor say what he'll do next about Rikers now that he's seen something whatever it was for himself.

Jake Offenhartz: He's presented this plan that involves pressuring the union to stop the rampant absenteeism and address intake and address healthcare problems. It was very much, "Stay the course. I've confirmed that the plan that I put in place last week is on track and we are going to stay the course," basically.

Brian Lehrer: WNYC and Gothamist reporter, Jake Offenhartz, who accompanied the mayor as a reporter on the mayor's visit to Rikers Island yesterday. Jake, thanks a lot.

Jake Offenhartz: Thanks, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: Now WNYC's George Joseph from our Race and Justice unit and Akash Mehta from the investigative news site, New York Focus, on one of the reasons Rikers went from being almost empty to dangerously overcrowded during the last year. Their article together is called Crisis At Rikers: How NYC Judges Fueled An Increase In The City's Jail Population. Hi, George and Akash. Thanks for coming on WNYC again today. Good morning.

George Joseph: Good morning, Brian.

Akash Mehta: Good morning. Thanks so much for having us.

Brian Lehrer: George, I see a lot of this is about how much bail judges are setting for people being arrested and accused of crimes. Are judges doing something different from in the past?

George Joseph: That's a complicated question, Brian. Judges have long been under New York state laws that regulate how they can impose bail. Those laws, as of course you remember, changed when the legislature in 2019 passed bail reform laws. What that reform did was take away a bundle of charges that judges could no longer set bail for, but it allowed judges to set bail for a variety of violent felony allegations and a few others after the reforms were tweaked.

That being said, those types of decisions were supposed to be premised on the notion that a defendant was a flight risk, meaning they're likely to skip out on court. What our reporting showed though is that very often judges have been setting bail even for people who do not pose a high risk of flight, and because so many of these people are fairly low income, they're not able to post such fails and end up staying in jail.

Brian Lehrer: I want to open up the phones here for this portion of the Rikers conversation. Listeners, we would love to hear from anyone with recent experience in the court system on how bail is set right now and the role of judges in expanding the Rikers' population. Help us and help New York Focus report this story, 646-435-7280, 646-435-7280. Are you someone who's being held right now because you couldn't make bail? 646-435-7280. Are you a criminal defense attorney or a prosecutor involved in cases like these? 646-435-7280. Are you a judge, hello, judges, hello, your honor, who would like to explain how you make bail decisions?

Seriously, judges, some of you have called in before. We would love to hear from you on this, as well as the people who come before you, 646-435-7280. If you're at any place in the bail or not bail or how much bail pipeline, we invite you to call and give us your experience and how it relates to the dangerous conditions at Rikers. 646-435-7280, 646-435-7280, or tweet @BrianLehrer. Akash, most of the complaints we hear about bail in the media are from the mayor and police commissioner and more conservative politicians saying the recent bail reform law in New York state is allowing too many dangerous people not to have any bail after their arrests. How do the judges even have this much discretion?

Akash Mehta: Sure. As George mentioned, the 2019 bail reform did remove a lot of discretion from judges on certain charges, but on many charges, judges still have the discretion to keep people in jail or to set bail on them, which usually means that they stay in jail. Yet they are only supposed to do that in order to avoid defendants skipping out on trial. Yet, what our reporting shows is that about 75% of violent felony defendants are recommended by the city's own algorithm to be released without conditions based on their likelihood of returning to court and yet judges are only releasing 26% of them without conditions. What this effectively indicates is that by and large judges just aren't following this law.

Brian Lehrer: George, if you want to add to that, go ahead but if judges aren't following the law, if that's your allegation in the article, what's the recourse for that?

George Joseph: Just to explain that a little bit further, Brian, there's a lot of confusion about what bail is for officially versus what it's used in practice for. In New York, unlike in other states across the country, judges are not allowed to use the idea of a defendant's perceived danger to the community in making their bail decisions. They often do anyway because they're afraid of if they let someone out pretrial and they go commit some offense, they'll be on the cover of the tabloids.

In criminal court, we see this game constantly being played where judges are imposing bail, claiming it's about flight risk even though the city's algorithm says there's basically no flight risk here, but really what we're talking about is a public safety concern. That's why there is so much of a disregard for the law but because everyone understands the dynamic, it just goes on.

Brian Lehrer: How much bail are we talking about? Akash, for what kinds of alleged crimes? I think most of the listeners who have no connection to the system themselves have no idea how much bail is for.

Akash Mehta: We're talking mostly about violent felonies. In about 98% of cases, we're talking about at least $1,000 in New York City. For the vast majority of defendants, that's not money that they have to post. That's why you see two-thirds of defendants still in jail a week after bail is set because they can't pay it. Most of them are there for months. One thing I think is really important to pay attention to when we're talking about these fears of violent crime especially over the last year where we've seen some increases in some types of crime is that there's a lot of research on the effects of pretrial detention, so the effects of keeping someone in jail before they've been convicted of a crime on overall crime rates.

What this research shows is that, yes, in the short term when you lock someone up for a few months, clearly they're less likely to commit a crime, but in the long term, you actually drive up the rates of recidivism because you're tearing people away from their jobs, from their housing, from their government benefits, from their communities. A lot of research shows that over the next few years, they become significantly more likely to commit crimes.

Brian Lehrer: George, that's a tough one, though, for a lot of people in the public to swallow that long term potential gain of rehabilitation and reintegration versus if somebody's getting bail because they committed a violent crime and are deemed by a judge to be a potential immediate threat to public safety to keep them behind bars at the moment.

George Joseph: Yes. I will say, Brian, that research has found that a very, very small percentage of defendants even those accused of violent felonies who are let out go on to be rearrested for any sort of crime. That's what the data shows. However, there are situations where judges have that exact fear that you're talking about. We reported on one in our story. There was a man named Segundo Guallpa who was accused of a pretty violent domestic violence incident against his wife. For years, he had been suffering from alcoholism in part because of a work injury that left him unemployed in which two of his fingers were cut off in a construction accident.

Then later because of a brutal robbery that he himself endured, he fell more and more into alcoholism and eventually became more and more of a violent presence at his home. After one incident with his wife in August, she had her family call 911, and he was arrested, she wanted him to get treatment, she wanted him to get rehabilitation and she also wanted to be safe and separate from him.

At the arraignment court hearing, that variety of options and resources that would be necessary to help someone like that weren't on the table. The judge was deciding on a protective order, which he granted and on bail which he set even though the city's risk algorithm said he should definitely be released, he has very low risk of skipping out on court. The judge ended up setting a bail which this man's family says he could not afford. 11 days later, he takes his own life at Rikers because that's how bad the situation is there.

Brian Lehrer: Let's take a phone call from Rikers Island. This is Nathaniel on Rikers, you're on WNYC. Nathaniel, thank you for calling in.

Nathaniel: Good morning. I just like to say I've been incarcerated since January of this year and my bail was set at $10,000 which I can't afford. At the same time, while I'm in here, we had two times out of nine months linen change to change our seats and blankets. At the same time, the condition when the mayor did come over here yesterday, he didn't come to the park where we live at. He just came in the part where they start [unintelligible 00:21:06].

[horn]

Nathaniel: That's the part he came in. He came in the part where they were just painting and trying to make it look good for the camera. Excuse me.

Brian Lehrer: Why was your bail set at $10,000? Can you take us behind the scenes on how that worked in your case a little bit?

Nathaniel: Okay. My bail is set at $10,000. I fleed from an off-duty officer and he hurt his self and they charged me with a common assault on an officer. He hurt his self. I didn't know he was an officer. You know what I'm saying? It was four o'clock in the morning. I didn't know, somebody pulled out a gun and I ran. Whereas I'm running and when they did catch up with me, the officer said he hurt his self and now I get charged with a common assault. I've been down for a common assault and they was just trying to push one out of three to me. That's it. You take this one out of three or go to trial.

Brian Lehrer: I'm going to come back to bail in a minute which is the topic of this segment. Did you say there's a COVID lockdown again?

Nathaniel: Yes, we've been locked down in this house three times on COVID.

Brian Lehrer: What's the situation today and is it new?

Nathaniel: No, it's like they keep bringing people in who got COVID or somehow got COVID but you can't get to the clinic because you got to get on the phone to call the clinic and all they want to do is tell you you got your sick call. I ain't been a sick call in a month.

Brian Lehrer: In other words, you can't get an actual medical appointment?

Nathaniel: No, the only way you get a medical is you laying on the floor and they going to come to stretch and get you and they take their time to come get you on a stretcher.

Brian Lehrer: Nathaniel, thank you very much for checking in with us. We really appreciate hearing your story. Good luck to you.

Nathaniel: Thank you.

Brian Lehrer: As we continue with WNYC's George Joseph and from the news organization New York Focus, Akash Mehta, their article together is called Crisis At Rikers: How NYC Judges Fueled An Increase In The City's Jail Population. Of course, we know that that increase, the overcrowding is contributing to the rate of COVID now being above the general population and to the 12 deaths at Rikers this year, an unusually high number.

George, as I was listening to Nathaniel's call and thinking about his bail, $10,000. If I was arrested and they said $10,000 bail, I could pay it and I would be out while I was awaiting trial. He can't. We could have been arrested on the same exact charge for the same exact alleged crime, and one person would be behind bars at Rikers for inability to pay and one person wouldn't. How does that make sense?

George Joseph: Brian, that has been one of the rallying cries against the idea of cash bail in general. People who are accused of the same crime just solely based on their wealth are going to go to jail or be able to fight their cases pre-trial on the outside of jail. It's purely a class-based system.

Research has shown that people who are incarcerated in jail pre-trial before they've been found guilty of anything, in addition to potentially losing their housing, their jobs, their family ties, have a much higher likelihood of pleading guilty or getting a worse deal when they plead guilty because they're not able to fight their case, stay in their case, and go out and find information that could help bolster their side of an argument in a criminal case. Not only is it subjecting a certain class of people to detention, and given the situation at Rikers right now, we know that those conditions can be deadly, it's also creating adverse impacts in the long run for people's criminal history based on their wealth.

Brian Lehrer: Akash, from your understanding, to continue down this hypothetical, if I was arrested on the same charges as Nathaniel and considered the same potential risk to public safety, would the judge look at my finances and say, "Oh, he can afford $10,000 bail, so we're going to set it at $50,000 or whatever." Does that happen?

Akash Mehta: Yes. I think that does in some cases happen like in some white-collar crime that-- Again, the purpose of bail is to assure your return to court. If $10,000 wouldn't be enough for you and there would still be a risk of you fleeing trial, then potentially the judge could include that.

Brian Lehrer: They could take finances into account.

George Joseph: Brian, could I jump in on that point?

Brian Lehrer: Yes, George.

George Joseph: If you've ever been to arraignment hearings, you'll see they're very fast. Judges are processing people quickly, quickly setting bail, and having huge impacts on people's lives. In that hearing, a defense attorney and a prosecutor may get a little bit of a word in on what the defendant's job status is, how much they're maybe willing to afford, but this is often after just five-minute conversations.

Judges really have little data about how much someone actually could be able to afford and often are using their own presumptions which may be based on their own backgrounds about what is a reasonable bail. This system that we have right now does not provide the data for the courts if they even wanted to accurately impose bail.

Brian Lehrer: Let's take another phone call. I see that Tina Luongo from the Legal Aid Society is calling in. Let's see what Tina Luongo has to say. Hi, Tina. You've been a guest on the show. Now you're a caller. Thank you for calling in.

Tina Luongo: Yes. Hi, Brian. How are you? Thanks to the panel for raising some really critical points. Look, I think the first thing to the question you posed, Brian, the difference between you and let's say somebody who we represent, while it's class, let's also call it out, it's also race. By and large, if we were talking about a group of white people, there would have been a lot more action stopping the inhumanity of Rikers long before and the mayor would have gone, and he would have talked to people. Let's talk about that, but really let's talk about the judges and the information that they have.

While it is true that things move very fast, there are services right in the courtroom that the judge can lean on to release somebody, even somebody who may be charged with allegations of a serious crime. That's the supervised release program. That data shows is incredibly, incredibly positive means for people to be released in the community and come back to court. The city funds that. Yesterday, I sat in Manhattan where someone, a young woman was charged with the allegation of a violent crime. Clearly, just from our own observations, was in need of mental health intervention.

On supervised release, that caseworker was in the court and told the judge that they were willing to take this person into their program and work with this person in community to connect them to services. The judge set $25,000 bail and that person went in. At the time in which we are talking right now where the statistics that were just proven and shown is that hundreds of people aren't getting their medical treatment or their mental health treatment. What good did we just do? More importantly, that judge, what harm did he do?

The fact is that what you said earlier about the political reality of when the mayor goes on the record and says, "Our city is unsafe, roll back bail." When the commissioner goes on record to say, "Roll back bail, our city not safe," when by the way the data shows that is not true. What happens is DA's feel the pressure, judges feel the pressure, and they start to set higher bails and they don't start using those resources, and they put their heads in the sand right now as we are facing this crisis. That's what's going on.

Judges have to bear witness. I'd like the chief judge to go see what is happening at Rikers. I would like line district attorneys, not just the DAs but the people who are asking for bail, to go to see what is happening at Rikers. Unlike the mayor, I would like them to talk to the people like Nathaniel who just called in who say, "I'm being silenced and no one is hearing me." That's what we need. We need intervention to decarcerate and we need the political will to recognize the crisis and stop putting heads in the sand.

Brian Lehrer: Why in your opinion, Tina, would judges be remanding people with bail if they don't have to during the crisis?

Tina Luongo: They're afraid of their name being on the front page of perhaps the one time that maybe something will go wrong. That is a reality that if a judge makes a decision, and some judges do have the humanity to see the person in front of them and to connect them to services. We have had very successful mental health courts in all of our boroughs, and particularly Brooklyn, where those judges are actually investing in the resources to bring people to community because they know the harms of incarceration.

By and large, the judges like the 10 judges that are on that list, I believe are motivated by their fear of having their name associated. The reality is that's about our need to invest in treatment and not jails. Our city investing in housing to re-enter people like the Exodus program that we have been using during COVID, which are hotels with mental health and treatment attached to them so that we can stabilize somebody through reentry and get them to services.

We need judges to realize that by and large their decisions to release somebody to community not only follows the law but is successful in a large number and stop being afraid that their name is going to be on the front page and be motivated by that. They need to put their eyes on the problem and not be in denial. We have been bringing all the affidavits to court and judges are basically saying, "I'm hearing the problem is solved," and clearly it's not.

Brian Lehrer: The Rikers problem. Tina Luongo from the Legal Aid Society, thank you for calling in.

Tina Luongo: Thank you.

Brian Lehrer: We just heard from a legal aid lawyer. Here's a former prosecutor calling in. Don in Brooklyn. Don, you're on WNYC. Thank you for calling.

Don: Hey, good morning. I got to say the characterization of this issue by Akash and even by the gentlewoman from Legal Aid Society is a bit preposterous. This state implemented rule changes for everything from bail to discovery a couple of years ago. In spirit, they were great, but in reality, what's happening now is you have people that create content and you have people that are heading organizations that are making the issues seem worse than it is. If we're talking about overcrowding in the jail system during COVID, that's one thing, and that is something that absolutely needs to be addressed.

To mischaracterize the issue on bail as an issue of flight risk and et cetera, et cetera, is just not true. The bigger issue is that New York state and Alabama have completely different laws. The New York state system and the federal have completely different rules and laws and they treat everyone differently. Now we're hearing about studies about how bail impacts X, Y, and Z. A lot of these things are significant. If you're looking at New York City what's even more significant than that is Manhattan is its own island. Staten Island is its own island literally and figuratively in that they do whatever they want to do. Meanwhile, in Brooklyn where I used to work, and in the Bronx, things are very different.

While bail can be imposed when a defendant is at flight of risk, the state also carved out certain rules for violent crimes and that sort of thing. Yes, a judge can impose bail even when someone isn't a flight of risk when someone who's being accused of murder or robbery or choking a domestic partner or something like that. Those are completely different things. What Akash is not talking about is how judges can't use risk to the community as a consideration for setting bail.

These are the kinds of things that we're dealing with, but more importantly, folks like Akash, folks like Legal Aid Society are making the situation seem worse than it actually is when people do have access to mental health services, people do have access to supervised release. Any time bail is even a consideration, judges have authority where they say, "I have to impose the least restrictive method to ensure this defendant's return to court, including supervised release." If defendants are, generally speaking, of course, there's going to be certain instances that slip through the cracks. These things are happening and change takes time.

Meanwhile, while things are changing and while it's not completely perfect, the same voices are just going on and on and on about how the system is broken without any actual attempt at fixing. It's starting to sound a lot like Mothers Against Drunk Driving where the head of that organization actually quit the organization when every state just kept on trying to impose more, more, and more and more restrictive laws against drunk driving when she was like, "Whoa, whoa, whoa, wait a second, our goal was to keep drunk drivers off the road, not to make a whole sub criminal system of going after people for just drinking one or two beers and getting in the car."

Brian Lehrer: Don, let me leave it there because you put a lot on the table and we're up against the end of the segment. Thank you for all of that. Akash, he was mentioning you but I should remind everybody that this story was jointly reported by Akash Mehta from the news organization, New York Focus, and WNYC and Gothamist reporter, George Joseph. I'll let you each reply and then we're going to be out of time. Obviously, we will continue to follow the situation at Rikers Island. Akash, what were you thinking?

Akash Mehta: Great. I just want to clarify one thing, which is that the reason we're focusing on flight risk is not because George and I think that. That's not an opinion of mine and George, that's the law. That's the only permissible reason for judges to set bail including on violent felonies. It's true that there are differences between different boroughs. On bail eligible cases in Manhattan, it's about 56% of the time that judges set it, whereas in Brooklyn it's about 47%. What we're seeing across the city is that judges are setting bail at far, far, far higher rates than the data shows that people are likely to actually return to court, which shows that they are violating the law.

The last thing I'll add is that prosecutors are also requesting bail in cases which are not flight risks. One thing that was interesting is that three times in the last two weeks, we have seen prosecutors or court spokespeople on record, press spokespeople, saying that the severity of the charges or the risk to the public is the reason that they're requesting or setting bail, including the Bronx DA said this to my colleague, Sam Mellins when he reported on prosecutors last week. The Brooklyn DA, Eric Gonzalez, had said this. Of course, spokesman said this to me and George. What this shows is that they are brazenly-- The press spokespeople are admitting to violating the law, which just shows how little this law is understood.

Brian Lehrer: George, 30 seconds. Last thought.

George Joseph: Brian, I would say that even for very violent crimes such as murder and that sort of thing, there can be, in the city's assessment, flight risk associated with that. It's not like if you were to follow the law as it stands, there would be no more pretrial detention. There seems to be continually a conflation between the flight risk issue and the public safety issue. If advocates like the caller want to change the law to account for public safety like in other states, they should push for that, but we can only report on what the law actually says versus how it's being followed, not on how someone would want the law to theoretically be followed.

Brian Lehrer: George Joseph from WNYC and Gothamist, Akash Mehta from the news organization, New York Focus. Their joint article which you can read on Gothamist is called Crisis At Rikers: How NYC Judges Fueled An Increase In The City's Jail Population. Thanks to both of you and callers from the various points of view and the various aspects of this system, thank you all for calling in. George and Akash, thanks.

Akash Mehta: Thank you.

George Joseph: Thank you, Brian. We missed you at softball season this year.

Brian Lehrer: [chuckles] Next year.

George Joseph: [chuckles] Okay.

Brian Lehrer: Spring training. Brian Lehrer on WNYC. More to come.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.