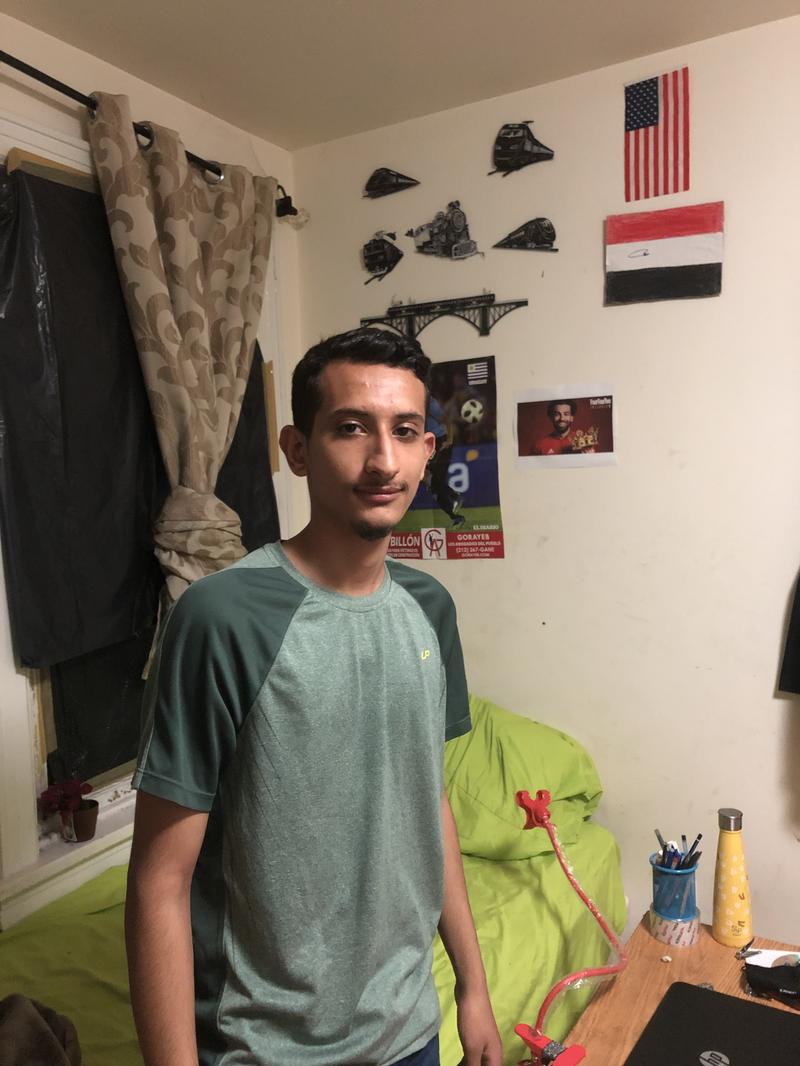

Hisham Alamari fled the civil war in Yemen in 2015 as a teenager and, after two years as a refugee, reunited with his father in the Bronx. His new school has offered support but he struggles to focus. With his mother and two of his siblings in legal limbo, stranded in East Africa as a result of the U.S. travel ban, his mind and his heart are often elsewhere.

He is one of an estimated 3,300 Yemeni-born children living in New York, many of them separated from loved ones. Of all the nationalities included in the travel ban, Yemenis account for the majority of family separations. The ban has kept out more than 5,000 Yemeni spouses, fiances, or children of U.S. citizens, according to a Cato Institute report.

“He said the mother is everything. He can't say no more,” explained Hisham’s father, Rashad Alamari. “It's like the air for life.”

And that’s where International Community High School in the Bronx comes into the picture. It enrolls dozens of students from Yemen, including Alamari. Its staff members work to help fill the void left by these absent relatives, especially the women as the men in the family came to the United States first for work.

"With this travel ban...we've experienced situations with our boys where they're completely disconnected from the women in their families," said Principal Berena Cabarcas. "And that for us is incredibly detrimental."

Someone that Alamari is particularly close to at school is an Arabic-speaking aide named Nassira Hamdi. A petite woman with a soft, warm voice, Hamdi was born in Morocco and speaks four languages -- English, French, Arabic and Berber. When Alamari attended English class this past school year, Hamdi often sat by his side, translating what the teacher said.

"Hisham, when he came here first, he doesn't even know the alphabet," she said. He’s made a lot of progress since then, but she has to work hard to encourage him to focus on his education instead of his worries.

"His mom not being with him is a big gap in his life," Hamdi said. "Kids they are talking about their mom, they're going home, but he feels, where is home?"

Alamari's home is in the Pelham Bay neighborhood of the Bronx. He lives there with his brother and his father, Rashad, who is gone working at a grocery story almost all day. He comes back at 10 pm, feet sore and body exhausted.

For decades Rashad Alamari traveled back and forth between the U.S. and Yemen, earning a living to send to his family. He even became a U.S. citizen.

"This is my home, it's where I make my money, it's my home," he said. "It's like I love this country too much."

And that’s why he’s fighting to get his wife, Arwa Anam, and their two younger children to New York. When the elder two sons came over from Djibouti in October of 2017, Anam got a visa to join them. She was waiting only for it to be printed. Then the Supreme Court ruled that Trump's travel ban could go into effect while litigation continued. In 2018, the court upheld the ban completely.

The family is part of a lawsuit that the Center for Constitutional Rights is about to file on behalf of dozens of Yemenis who are both related to American citizens and had their visas approved before the ban went into effect.

Dialas Shamas, an attorney at the Center's headquarters in New York City, said that when she visited Djibouti, the only thing worse than the intense heat was the waiting.

"I think one of the things that's most striking is this sort of state of limbo and how it's so palpable and frustrating, for lack of a better word, for these families," said Shamas. "I mean, so many people we met with were the for over a year, just waiting."

Alamari credited his high school, and especially Hamdi, with encouraging him to do something with his life besides endlessly waiting. His father agreed that she was more of a family friend than a teaching assistant at this point.

"He feels like she's his mom," he said of his son.

Hamdi was hired in 2008 to be a para-professional at the high school. Most paras get their salaries from special education funding and are there to help only one or two students, but the school uses money from its regular budget to pay Hamdi so she can work with many students.

She's with them in class, in counseling sessions, and on the phone with their families. She’s also with kids when they first enroll in the school.

"For me, it's the equivalent of imprinting on someone," Cabarcas said.

During enrollment, Hamdi interviews the students to find out if they have any gaps in their education -- which many do, because of struggles related to immigration. Hisham missed out on two years of school when he fled the war in Yemen.

With the help of CUNY, the school developed an intensive curriculum called Bridges that’s designed specifically to help students who are not only learning English, but academically behind even in their home language. Administrators credit Bridges as one of the reasons that the school’s four-year graduation rate rose from 59 percent to 81 percent in eight years.

But staff said they were concerned about feelings of hopelessness and despondency among their students. Principal Cabarcas said she's seen a rise in the number of her students expressing suicidal thoughts.

The school has hired more counselors and two more Arabic-speaking paraprofessionals. They're also trying to learn how to be more sensitive to Yemeni cultural norms. She said she and her teachers have learned it's not appropriate to hug a Yemeni student, something that's hard for Cabarcas when she sees a student in pain.

"We as staff members, really can't hug them or just give them the kind of affection that they really are starving for," she said.

Hamdi said she can sense how much Hisham misses his mom, even if he acts stoic.

"He doesn’t talk that much, but I can feel him, I can see," she said. "He’s always sad in the classroom. You can feel that something’s going on with him even though he doesn’t talk."

For his final English project this past school year, Hisham wrote about a character in the novel The Color of My Words who gets her power from writing. When asked what gave him power, he immediately said, “Ms. Nassira.” Hamdi, who was translating the conversation, laughed in embarrassment.

Then she asked him: what is his power?

"Sabr," he answered in Arabic. "Patience," Nassira translated. "Patience is his power."

This story was produced by the Teacher Project, an education reporting fellowship at Columbia Journalism School.