( New York Academy of Medicine) )

Dr. Benjamin Simon argues that hypnotism is a valid form of medical practice, but that it has been sidelined for historical reasons.

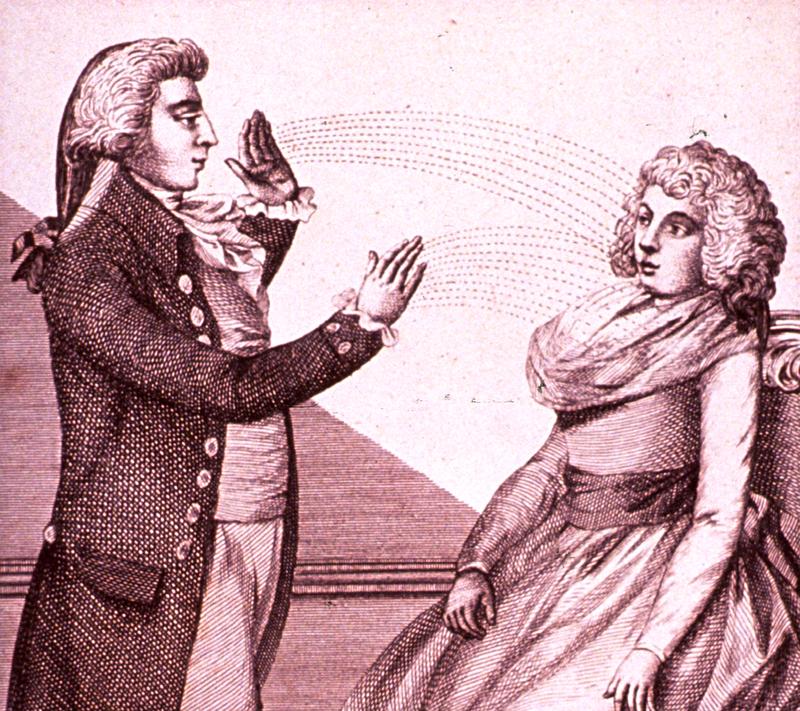

He begins his lecture with a description of the early history of hypnotism, tracing it back thousands of years to the Egyptians and to Biblical times. The lecture then shifts to 1734, and Frank Mesmer’s revival of hypnotic practice. Mesmer’s efforts were rejected by the medical institutions around him, Dr. Simon argues, partly because of the “hostility of entrenched medicine,” and partly because Mesmer, like many who followed him, converted his practice in a “cult.” He was too reliant on dramatic flourishes, like a brilliant silk robe and arrays of iron rods.

Dr. Simon goes on to describe many re-occurrences of hyponotic practice across many counties, including France, England, and India, and then debunks some myths about hypnotism. He explains, for example, that hypnotism is less about “the piercing glance of the eye,” and more about the assertion of authority. (This, he explains, is when men enjoy practicing it, and why young boys like to practice it on young women… who in turn enjoy it because it gives them a chance to be submissive.)

He discusses Charcot and eventually Freud’s explorations of hypnosis, and explains that hypnosis taps into the unconscious. Hypnotizability, he says, is not a mattery of “weak will,” but instead a matter of connecting to unconscious desires. A person can be convinced to commit a crime, but only if his hypnotizer is a prestigious figure, and only if the crime is an extension of his unconscious needs or wishes, he claims.

Dr. Simon then describes several hypnotic techniques, including the administration of drugs. “Sodium Amytal, Pentothal, used will reduce, will relax the patient, reduce their resistance, and often under such drug, hypnosis can be induced where it could not be readily induced in the waking stage,” he says.

Patients will rationalize their actions under hypnosis, he says. He gives an example of “one of his favorite suggestions.” He would hypnotize a patient and convince them to rise, give the Nazi salute, and call “Heil Hitler!” whenever he said the word “German.”

“I'd wake them up, engage them in a conversation about their war experiences and how terrible they were and how they must hate the Germans. And they would keep on. But I always used the word Jerry instead of German. And I would get them into a good discussion of how they hated the Germans and what they'd like to do to them. And then I would let slip the word German instead of Jerry. In which case, right in the middle of expressing hatred of Germans, he would rise, give the Nazis salute and yell Heil Hitler.”

Each patient then tried to explain their actions, with the exception of one Czech man, whom he could not convince to say the words “Heil Hitler,” despite repeated attempts at hypnosis.

Dr. Simon then describes his own experiences under the influence of hypnosis, before transitioning into a discussion of its benefits and limitations as a form of anesthesia, and the various legal implications of the technique.

The lecture ends with a question and answer session.

(Automatic transcript - may present inaccuracies)

>> Time is of great interest to us tonight because we're going to see a unique example of a science and art, a philosophy, a religion, which has occupied the interest of people as a mystery at first and at various other aspects for many centuries indeed. Hypnosis has actually been practiced with a known history over 3,000 years. Largely religious as I said in its earlier days. It was recognized as hypnosis under another name for the last two centuries. It has interested persons for very obscure perhaps and mysterious reasons. I think most of you, particularly the males, will recall your early childhood interests in such things as Lionel Strongfort and Charles Atlas which you could read openly in the boy's magazines Popular Mechanics and what you will and perhaps send for the literature on how to become a strong man. Later, interest in jujutsu and secrets of power over persons and people. And then most boys have surreptitiously read, and some of them had the courage to send for the information on how to hypnotize. For a boy it was a difficult thing fortunately. And most of them perhaps got the ten cent folder and then tried a few passes, particularly on the little girls, who were also interested because of their particularly feminine desire for submission and the curiosity of a similar order. The secrets of life, the mysterious magic by which one may acquire power over others, an essential aspect of development of the personality. It's interesting how this divided into the two sexual divisions. The dominance of the male, the submission of the female. And it is very interesting today that there are very few women hypnotists. We see this same psychological need exercised in the search for the elixir of life and Ponce de Leon and others, seeking for a mysterious power. Fountain of youth is still the same thing, how to be strong, powerful and forever omnipotent. Today, we are seeing a sort of renascence in the interest of hypnosis. Perhaps different from what has gone on in the past. We have seen in the history of hypnosis a continuity passing from man to man almost as a personal transference. In the last several decades, this has not been related, since the days of [inaudible] has not been related to an individual and is beginning to take its place as a focus of interest. A science if you like or an art or a religion. Today, we see this interest manifested in a good many ways. We are gathered here, and I say this with no, with no invidious sense because I think behind most of you is a feeling that I had when I was first hypnotized. A wished feeling of mystery of all at the strange thing that can happen to human beings. And a wish somehow to share at least in the power producing aspect of it. Now as I've said, hypnosis has been practiced for over 3,000 years. In Egypt, there were well-established sleep temples where one distressed with life might go and in which they would be a laying on of hands by the priests, and the patients would go into a sleep from which they would emerge refreshed and relieved. Laying on of hands is quoted of course, is stated in the Bible. In the orient, we know much about the activities of the fakirs and the holy men. We know the effect of totem in tribal rites and religions. Many produced by hypnosis, taboos rather. Hippocrates, father of medicine, said the affections suffered by the body, the soul sees quite well with shut eyes. Asclepius treated patients with deep sleep and stroking. Avicenna in the 10th century expressed the idea that there could be influence on human beings by the imagination. [Inaudible] in 1462 said somewhat the same thing. Paracelsus in the 16th century, one of the great physicians, was persecuted and driven from the city because he stated that imagination and faith could cause and remove disease. Edward the Confessor was the first to exercise the royal touch. And the power of the royal touch akin to the stroking was recognized by the church. In 1662, an Irishman, an Irish healer, Greatrakes, claimed that all disease was due to evil spirits. This is very much not only the earliest aspects of hypnosis but psychiatry in general. He commanded the spirits to depart by making passes over the patients. And many were cured. A hundred years later, an ex-monk Father Gassner, drove out evil spirits by exercising them in faultless Latin and claims to have cured and has said that he cured 10,000 patients. Then on May 23 in 1734, we began the renascence so to speak of the man-to-man succession which I mentioned. There was born then Franz [inaudible] Mesmer mentioned by Dr. Braceland. He was born in Germany. He was to be a priest and was so educated, but he gave it up because of his greater interest in physics, mathematics, and astronomy. And in those days, astrology was included. He was greatly affected by the stars, the mystery of the heavens. He went to medical school in Vienna. And in 1765 published his medical thesis, The Planetarium Influx, in which he stated that there was a magic fluid from the stars affecting the body fluids and that there were many evidence of these mysterious magical influences. He interested Father Hell, the court astrologer to Maria Theresia. Hell believed that magnets had curative powers. And he made magnets in the shape of various organs of the body. The perhaps is the first manifestation of homeopathy. Apparently these magnets were not too valuable to him because he traded some of them to Mesmer for some of Mesmer's essays on planetarium influences. And Mesmer put these magnets to use and became very successful in healing. However, he soon found that the magnets were not necessary and that he could do the same by making passes with his hands. And actually he treated Mademoiselle Paradies, a blind woman, a favorite of the Queen and cured her of her blindness. This would recognize today clearly as a hysterical blindness. Then began the other aspect of the history of hypnotism, the hostility of professional and entrenched medicine. Mesmer was severely criticized and was in dishonor with his own profession. He left Vienna and went to Paris where he immediately acquired a great number of patients. There too he suffered the opposition of medicine. Now I want to say right here that I don't propose to attack the medical profession for its opposition to progress. I think here we will see as we will see it continued throughout history, the danger of cultism. I will try to show that there is no question of value of hypnosis in the field of medicine. But it suffers from the fact that those who practice it, I won't say those, but some who practice it. And unfortunately the most articulate of those who practice it often make it a cult and make it the only form of practice. And I think in many respects, the fighting for a cause, as was mentioned by Dr. Braceland, has resulted in some opposition which would not necessarily occurred at least to the same degree. Mesmer ran into trouble in Paris. He went to Belgium but finally came back. He honestly believed, as far as I can tell, that he had this magnetic power to cure people. As Dr. Braceland suggested however, there was a tremendous amount of, well it was called charlatanism, but certainly a dramatization, he had this large room, in the center of which was a bacquet, which was a large tub containing glass, iron filings, bottles and water. These were all magnetized by Mesmer and from these, from this bacquet extended some jointed iron rods, perhaps 30 of them. Patients stood or sat around this tub, connected themselves or touched the rods, and then Mesmer would come in a brilliant robe, a brilliant silk robe. There would be [inaudible] music and then silence. He fixed his eyes on each patient in turn, passed his hands over their bodies, and then touched them with an iron wand. Two to three treatments and they were cured. The public interest in this was so great that a commission was appointed by the Academy of Sciences, a commission of about nine which included such great names as Lavoisier, the father of modern scientific methods. Guilotin, the father of what you will, and our own Benjamin Franklin. This was partly initiated by a dispute with his disciples. This commission set up what they considered controlled experiments. They magnetized a tree for example and found that a previously hypnotized boy who got within 45 feet of that tree immediately had convulsions. They did not, and became unconscious. They did permit Mesmer to perform his own experiments. They decided there was no such thing as animal magnetism, but that this was the imagination. So this commission nearly 200 years ago, said what we have learned today. That this was the imagination in the broad sense of the word. But of course, not being prepared psychologically for all the scientific aspects of imagination, they discredited Mesmer and the Royal Society of London brought out a similar report. And Mesmer left France. What Mesmer brought out was something that, Mesmer came to his peak in the wake of the great work of Parnell [phonetic] and [inaudible] in the treatment of the mentally ill, of the insane of the day. What was not recognized and wasn't recognized even then when it happened was the tremendous mass of neurotic persons in the world. And it was the great mass of these who flocked to Mesmer and to others who practiced hypnosis and were not recognized for many, many years to come. It was the acutely insane that were recognized as mentally ill. These were the persons seeking some help in getting harmony in their lives and could only find in this relief, and many did. In 1784 the Marquis de Puysegur, a disciple of Mesmer, discovered interestingly enough, that when a shepherd, a victor, fell asleep, instead of having convulsions, he went into a somnambulism state akin to sleep walking. [Inaudible] of Leon describe other phenomena like catalepsy. And so by 1825, practically all of the phenomena which we know today in hypnosis, at least in the clinical non-experimental practice of hypnosis were known. In 1819, [Inaudible] just fresh from the Far East found that if he gazed at a patient and shouted sleep, the patient would go into a trance, and he claimed that the trance was due to the patient and not to magnetism. He was considered a charlatan. The battle with the conservatism increased. And I have mentioned what I think are some of the faults in this. In 1837 Dr. John Elliotson, a respected London physician introduced at the University College Hospital for the treatment of nerves, diseases and anesthesia, hypnotism. This was banned by the counsel, by the University under the name of mesmerism. Interestingly enough, a little before this, Elliotson, the first man to use a stethoscope in England was attacked for his use of the stethoscope. And he was derided for carrying around this little piece of wood. The earliest stethoscope were a little wooden tube like the trumpet of a deaf person. So you see it wasn't just the mystery of hypnosis, it was the attack on established orthodoxy and the danger of ever deviating in any way. Another example, war. By then hypnotism had come to a stage then when it was used for anesthesia. War had amputated a leg under mesmerism. Marshall, another physician charged that the patient was an imposter, that it was probably the fact that he could suffer this amputation was probably due to the fact that he had a neurological disease which obstructed the pain organs. The pain tracts. Probably eight years later, Marshall insisted that this patient had confessed that he had felt pain. Yet this patient had undergone this amputation. We know that a hypnotic patient can feel pain, a hypnotized patient. But it has a different characteristic. Copeland argued that it was a natural and biblical law for people to suffer pain and that they should suffer. There should be no alleviation of pain. In 1845 Esdaile in India performed 300 major and several thousand minor operations by the use of mesmerism. In the meantime, La Fontaine, a Swiss magnetizer was giving exhibitions in England which were observed by James Braid, a physician of Manchester. La Fontaine incidentally, was forbidden by King Ferdinand of Italy to make the blind see or the deaf to hear. This is at the request of the church which considered the performance of such miracles a blasphemy, a blasphemous imitation of Christ. Despite the fact that Pope Pius the 9th received La Fontaine and said, well Monsieur La Fontaine, let us wish and hope that for the good of humanity, magnetism may soon be generally employed. We've seen this today too where the Pope and the church has exemplified and other aspects don't quite agree. Braid in the lecture of 1841 intended to expose La Fontaine. Instead, he saw that the trance produced were real. He studied these and came to the conclusion that it was due to eye fatigue. The interesting thing in hypnosis. Still today there's the idea that the piercing glance in the eye is the thing that does it. You can do, a blind man can do hypnosis without any difficulty. Braid fastened a cork to the forehead and had the patient try to look at the cork or he would use a bright lancet of which this little gadget I showed you is a modern development. And it was Braid who gave the practice the name hypnosis since he considered it akin to sleep, which is a thing that is endowed today. He realized that it was not sleep, but it was too late to change the terms. And so we have it. I think in the light of some of Freud's theories about the nature of hypnosis, I think the term sleep is not too far afield. Though it is not sleep in the same broad sense that we have of going to bed and going through a certain procedure. We know that certain mental activity takes place in sleep. But I will come to that I hope if I have the time later. Braid did not comprehend the idea of suggestion, though he used it. And later he used it alone. Braid got catalepsy, anesthesia without sleep. And wrote a book in 1843. I will have to hurry through this history a bit now as I see I have been taking too much time with. Braid rather messed up his work by his intense interest with phrenology. And he believed that every type of mental function was localized over a certain area of the brain and thereby projected to the skull. And by touching these areas he could produce all kinds of phenomena. At any rate, Braid's book on neuro-hypnology, the rationale of nervous sleep, probably got to Liebeault. And probably other information from Abbe Faria got to him. And we become aware in 1864 of the work of Liebeault, a practitioner in Nancy who practiced hypnosis with the addition of suggestion. He did some very excellent work, and he was least free of the charge of charlatanism because he never charged anyone for his work. Was a very kindly practitioner and well loved by his patients and others. He wrote a book Le Sommeil on sleep, which he sold one copy. Liebeault was followed by Bramble in England and then by the Great Bernheim, the professor in the School of Medicine at Nancy. Bernheim had written an article showing that Liebeault was a charlatan. But subsequently, a patient who Bernheim had treated for sciatica unsuccessfully for six years came to Liebeault and was cured. Berhheim went to the clinic to denounce Liebeault and remained to praise him. Bernheim was a practiced physician and a good scientist. He went to work on the matter. In 1884 he wrote the book De la Suggestion. In 1886 suggested therapeutics and to all of this gave great credit to Liebeault for his work. And the two of them were the Nancy School. About the same time, the great Charcot, the greatest neurologist of his time practicing at the Salpetriere, was decided to be ultra-scientific and study hypnosis as it should be studied. I can't go into details of just what he considered the scientific method. He treated three hysterical women, none of which he hypnotized himself. And he applied various methods that he used to study spinal disease. He revived the concept of magnetism which had been pretty well discredited by the Nancy School. He described lethargy, catalepsy, somnambulism and pseudoscientific terms for three stages of hypnotism. One produced by closing the eyes, the other one with the eyes opened. And the third one by touching the head. Today we would know that these are all highly suggested phenomena in which the patient acted out what he was expected to act out. They knew what Charcot wanted, and they gave it to him, as every patient under hypnosis does. He produced the phenomena by touching magnets. He could change contractions from one side of the body to the other by magnetic transference and various things like that. In 1888 he wrote Animal Magnetism in which strangely enough he was supported by another great scientist Binet. Though two years after this, Binet wrote La Suggestibilite, and later of course participated in the development of the Binet-Simon test, mental ability. There was quite a battle for time in the Nancy and the Paris schools. And in the second edition, Bernheim showed clearly that you could use a paper, pencil, a piece of cork or nothing and get the same results as one got with the magnets. And magnetism was then laid forever, except as we can buy them today in the form of magnetic belts, which you can get out of the Police Gazette and other various such magazines for a consideration of course. Bernheim's great interest was probably in the man who first proposed the concept of the irresistible impulse. A concept in which we deal today in medical legal psychiatry. And considered that this type of behavior was an automatism that the patient was on, in a state of suggested influence. Either self-suggested or otherwise akin to hypnosis. So 100 years ago we had this concept brought out. A side light to the history of hypnosis at this time lies in the story of Mary Baker Eddy, who was a hysterical born in 1821, suffering from fits and hallucinations She married a man named Garber and then a dentist named Patterson. She claimed to have spiritualistic powers. She spent after that several years in bed, paralyzed. Apparently her powers weren't able to conquer this paralysis. In 1862 she went to a mind curer, Phineas Quimby, who tried magnetism after seeing a French magnetizer operate. She was cured in a matter of days. She became devoted to Quimby, tried to adopt his practices, but was unable to do so. She failed, as will usually be the case of a very disturbed personality. She became a medium, exorcised the spirit of her dead brother. And I won't be able to go, perhaps they'll be time discussion into mediumism[M1] and its relation to hypnosis and autosuggestion. But certainly the honest mediums are clear instances of autosuggestion and the production of the commonplace hypnotic phenomena in which we know. On Quimby's death, Mary Baker Eddy got, that wasn't her name at the time, got his manuscript involving religion, spiritualism, diseases and so on. She added extracts from the Bible and then decided to write a book. She set out as a healer as I said and failed. But she became a teacher of others. And one of her pupils, Richard Kennedy, set up a healing clinic. She became jealous, which was characteristic of her life all the time. She accused him of trying to kill her by animal magnetism. And he broke with her eventually. She set up another school of healing instruction. Her pupils offered, rewrote Quimby's manuscript under the name of Science and Health, the First Edition. Later she accused a [inaudible] of malicious magnetism. So I will end the history of Mary Baker Eddy at that point. She later married Eddy and became of course the mother of Christian Science. Again, I impress you with the continuity from Mesmer, Faria, Liebeault, Bernheim, as you will go right to Coue, a transference from person to person. I haven't gone beyond Charcot. And I will shortly. In 1885, Liebeault met a druggist at Troy, Emile Coue. I think most of you who have known Coueism perhaps doesn't realize how far back he went into the history by this personal contact. Coue in 1910 established the so-called Neo-Nancy School. He had noticed the effect of waking suggestion without the deep sleep of somnambulism combined with drugs and often themselves, with drugs which were themselves ineffective. Coue established a free clinic like Liebeault's. He abandoned the trance and worked with the waking suggestion, much of which we know today as autosuggestion. Patients would be taught to recite if they had a pain in the back to focus attention on the pain in the back and say it is going 200 times if necessary as fast as it could be said. Sit down, shut the eyes, pass the hands lightly over the forehead, and this came to what you all know who saw him in the 30s here in this country, every day and every way I'm getting better and better. Effective in a great many cases. Now we make the greatest step from Charcot to Freud. In 1884, Sigmund Freud, a young neurologist, heard of Breuer's cure of a case of hysteria under hypnosis. He wanted to learn more about it. In the next year he went to Charcot in Paris. When he came back he worked with Breuer on hypnosis, and I need not go into what must be familiar to all of you, the discovery of the nature of catharsis under hypnosis. That in a hypnotic stage a person could express many things, and did express many things which were not possible for them to do in the non-hypnotized stage. Freud eventually found that there were many difficulties as I will tell you in the technique of hypnosis. And getting, and there are only a certain percentage of people who can be adequately hypnotized for that type of procedure. And Freud found that by a process of free association, similar results, even though it took longer, could be gotten in fact, probably better results. So just a word that I can't take the time to go that far into it. Now what's the history of the United States? A very interesting one. It's a very paradoxical situation. In the United States, that was a great deal of resistance from the general public to the ideas of hypnosis. It was not accepted as widely as it was in Europe. What was accepted, at least in later years in our time, in another way. In America there's a great [inaudible] for the stage hypnotist, the one who amuses the audience by his practices producing absurd behavior, which a patient is unable to control. This did a very great thing, which I think has helped hypnosis to get a stabilized position in American science. And that is it drove it into the laboratory where it could be studied as a scientific procedure. And so hypnosis has not been largely a medical practice in this country until recently, and it isn't a very widely experienced one now. But hypnosis, a tool in the hands of people like Morton Prince in his study of Sally Beauchamp and the cases of multiple personality, the production of association of the splitting in a personality. The reintegration of the personality under hypnosis where some of the phenomena took place in this country. It's interesting however that with the resistance to hypnosis as a medical practice in this country, as I said, it was widely accepted and still is today, everybody will flock, and everyone here has, most people here have seen the television shows. Everyone was probably interested, although it gave no demonstration of the fact of a hypnotist on his show last night. And they're widely watched. And you watch for the shows in the theater. In Europe, most places in Europe, these type of performances are forbidden by law. Now while there were others in America working at a clinical level, McDougall in psychology and so on. And 25 years ago some of the finest work done by Clark Hull. Some of the finest work done by Clark Hull in the laboratories of Harvard University. And other schools were started. And this has continued to this day. Now, what is hypnosis in a practical sense? You see I'm not going into the question. I'm not attempting to answer Dr. Brayson's [phonetic] statement that it's all a fake. I don't think there's any need to argue that part. The phenomena takes place. It's readily observable, and I think there could be no question of that. The fakery, if there is, is in the actual characteristic of the phenomena. And that I'll try to get to. Who can hypnotize? Well the answer is any intelligent person. That's an actual fact unfortunately. Who can be hypnotized? Again, any intelligent adult. Most children, in fact children are generally easier to hypnotize above the age of seven. Who can't be would largely be very psychotic individuals or very young children, or the mentally deficient. Will has nothing to do with it whatever. Quite the contrary, the concept that hypnotizability is a manifestation of a "weak will" is false. The factors leading to hypnotizability are the intelligence of the individual. His conscious willingness and the unconscious resistance or submissive that he may have, which is not always manifested on the surface. The question always comes up, can anyone be hypnotized against his will? I think most of us would agree yes. But not in, I can't go too far in qualifying this. For I will quote an example of Estabrooks in which he was having an at home and at home for a well-known stage hypnotist. The hypnotist, he had several graduate students there who were a bit snobbish and arrogant concerning themselves above a man of this caliber, and were somewhat discourteous. One particularly so. And this man was exceptionally discourteous to this man, quite rude. The hypnotist recognized what was going on, and finally he walked up to the man, grabbed him by the coat collar and says, you're going to sleep. And that's all there was to it. The man went to sleep. And I have done such thing. I'm sure any hypnotist who's practice has. Now this man was resistant. But what this hypnotist recognized, what I wish some psychiatrists could understand too about the unconscious. This man was fighting openly because he was submissive, very suggestible and was afraid of it. And therefore, it took place. Now where there is, and in hypnosis where there is a strong resistance to the phenomena that's being produced, the patient will be difficult to hypnotize and in hypnosis may not carry out all the commands. Which will answer the questions, can you make someone commit crime in hypnosis? Yes I guess you could. How far he could go, how far he will go will depend on many factors. The extent, degree of relationship with the operator. The consider-ability of the crime with his own unconscious needs and wishes. And actually how much he might feel he could use the operator that has the source of responsibility for. In other words, if he wanted seriously to commit this crime and could use the operator to get away with it, there's a strong possibility he might commit it. These things have never been brought to the absolute test. You're not going to give anyone a chance to commit a murder to try to prove something scientifically. But the weight of evidence seems to indicate that the question cannot be answered in an absolute yes or no. It's yes and no. Now, what are the factors that are involved in hypnotizability? Probably the most important which gives us our greatest clue to the nature of hypnosis itself, is the prestige of the operator or the hypnotist. Now the prestige may be expressed in many ways. On the stage, the stage hypnotist has the prestige of the big show, the lights, the crowd, the feeling that the crowd has toward him. The awe in which they hold him. And this is all effective and makes it easier for him to carry out his job. Prestige however in a physician involves with respect to the patient for the profession for the individual and many other factors of other similar order. Interestingly, Rosen, who has written one of our best clinical books on hypnosis claims that he hypnotized a good many of his patients against their will and without their knowledge. This I think is of great interest because of the care that people like Rosen and others use to protest the methods of the stage hypnotists who claim that he tricks the patient. Well, I don't know what it is. I use by choice the method of the stage hypnotist. And it is a method strongly dependent on prestige, authoritarian, I think it's one that can't be used by everybody. But it depends, you have to have a great deal of confidence in yourself and perhaps have a somewhat arrogant personality to be successful with it. It's not better than the other older techniques of induction of sleep by suggestion and by use of lights and flashes. It's a lot faster and is to me more positive. I think it's important to use the one that you're familiar with. I think it's wrong however to claim that one is doing, I think these arguments that you are tricking a patient. We use phenomena. The stage hypnotist uses phenomena, which Estabrooks says is keeping the patient off balance. The patient is made to clasp his hands, told to hold on and that he can't let go. And if he tries to let go you immediately suggest another thing for him to do to keep him off balance. I use the same thing, but I don't think that's keeping him off balance. I'm using a natural phenomenon. If you clasp your hands tightly, your muscles tend to go into spasm. You're automatically not going to be able to let go for a little while, not as quickly as if you hadn't been doing it. All of you have tried the stunt of standing up against a wall like this and pressing against it. Then when you step away your arm automatically rises. That's a natural overflow of muscular activity of the agonist against the antagonist. But you can use that phenomena to convince the patient that you're doing it, when you are not. And in that conviction, he begins to respect your prestige if you want. Or you can say that you're tricky. I don't say what you call it. If you're doing it for the benefit of the patient, that's the important thing. Now the question of patient staying asleep, using the term sleep [inaudible]. I think we're generally agreed that if left alone, a patient will wake up. And certainly, the vast majority of patients, by the suggestion of waking, will wake up right away. There are a few, and particularly those in medical treatment and some of the experimental procedures who get some satisfaction in the hypnotic stage who are not going to wake up and are not going to come out of their trance. They can, it can be done by proper handling the technique. Or in any case, they will wake up. Enough of that. Now, one more thing. One of the aids to hypnosis, if there is difficulty, is the use of drugs. Sodium Amytal, Pentothal, used will reduce, will relax the patient, reduce their resistance, and often under such drug, hypnosis can be induced where it could not be readily induced in the waking stage. What is the nature of hypnosis? I won't have the time to go into the stages of it. There are free, [inaudible] if you like. But 95 percent of people can be gotten into the life state of hypnosis in which you can reduce a certain amount of catalepsy to the eye lids, the inability to open them at will on suggestion. And a certain degree of suggestibility and a great deal of treatment can be done in this stage. The patient may or may not be amnesic. He may or may not remember what happened in this. Usually he will. And if he's told he won't, it may not take. In the medium stage, there is the ability to produce paralysis of, or inability to control, [inaudible] control of the larger muscles of the body which are called [inaudible] catalepsy. And in this stage, analgesic insensitivity to pain or hypersensitivity to pain, as you may want to suggest it. And in this stage, in some cases you may produce hallucinations. The individual may be made to envision and see things, a certain amount of crystal gazing and so on can take place. You may have hallucinations of touch, taste and smell. In the deep or somnambulistic sleep walking stage, anything if you like can happen. The patient will be amnesic for it unless he is told to recall it. He may have positive or negative hallucinations. He may be given post-hypnotic suggestions. Automatic writing may be produced. And the reincarnation phenomena Bridey Murphy if produced will come in that stage. In this stage you can reduce effects of the involuntary nervous system, the autonomic nervous system. Flushing, blushing or constriction of the skin, slowing of the pulse can be suggested and produced, and there is conflict among authorities, but I believe that one may actually produce blistering by suggestion of intense heat. The absurdity is, in hypnosis is an [inaudible] phenomena. The patient can do most absurd things on a suggestion and will not at all be affected by that. And to him they are quite normal things to do, quite rational. And if asked about them, he will develop all sorts of interesting rationalizations to explain these things and go far afield. I'd like to mention an interesting example of the case that I did however to show what the whole phenomenon of hypnosis is. This was a patient who was in the cataleptic stage, rather hypnotized. And in demonstrating him before my staff, I would suggest to him to show the effect of post-hypnotic suggestion. I don't have to describe that to you I'm sure. That one can suggest things in the hypnotic stage which will be carried out afterward in the so-called waking stage. Now this waking stage we do not believe is truly awake. As long as he's got that suggestion, he is in a sense hypnotized. But they carry out all normal activities until the clue or the key to this suggestion comes out, in which case he will perform it. Perhaps he goes back into a trance. Well one of my favorite suggestions in dealing with soldiers was to suggest that when I use the word German, the man would immediately rise, give the Nazis salute, and call Heil Hitler. And it's a very interesting thing because I would engage them. I'd wake them up, engage them in a conversation about their war experiences and how terrible they were and how they must hate the Germans. And they would keep on. But I always used the word Jerry instead of German. And I would get them into a good discussion of how they hated the Germans and what they'd like to do to them. And then I would let slip the word German instead of Jerry. In which case, right in the middle of expressing hatred of Germans, he would rise, give the Nazis salute and yell Heil Hitler. You asked him why he did it, he'd say well I just had the thought at that time. Or he might work out some other rationalization. But one man, this particular man, was a Czech. And he had suffered very considerable at the hands of Germans, as many of our Americans did in accept as a matter of combat relationship. And the first time I did this, he sweated. He trembled. He fidgeted. I thought he was going to wake up, but he didn't. He got up slowly, gave the Nazis salute and called Heel Hitler. I re-hypnotized him and pressed upon him that the word was Heil and this was the way it was to be pronounced. But I never could make that man say Heil Hitler. And he gave me various explanations. That's an interesting thing as to giving you a light not only on post-hypnotic suggestion, but on certain intrinsic controls that remain in the patient if you run up against a serious conflict in him. He'll do it if it isn't too much a conflict, and the hatred of Germans was more powerful than his attachment to me in the current situation. I think I'll have to begin to close. Just go into what we think today about the nature of hypnosis itself. I think I will quote White who brings out three points. He says the hypnotized person can transcend the normal limits of volitional control that we know. He believes without experience a will or intention, without the self-consciousness and without the memory, which under the circumstances one would expect. He behaves I mean to say. And that these changes occur merely because the hypnotist says so, all of which are the, either the fundamental characteristics of the hypnotic stage. The point is then that the function of the, the performance of the hypnotized person is goal directed. It has an object in itself. And I think this object I think was best described, this objective and phenomena was best described as [inaudible] by Freud in his discussion of group psychology and analysis of the ego. That the hypnotic state is a relationship between the operator, the hypnotist, and the patient. Depending as I have suggested along on many prestige factors, the operator is like the group leader. In fact the, Freud compares the stage in a hypnotic stage to that of a group of two, with the same phenomena. High suggestibility, contagiousness, the submissiveness and the need to submit to the leader. Similar to the manner in the primitives. That the process of suggestion of sleep is akin to the process of sleep as we know it. That the libido, the interest is withdrawn from the ego of the patient and his whole interest to body is restricted. Is withdrawn to itself, and there remains only that relationship with the operator. A relationship akin of that to the powerful, prestigious parent, to the child. And that there is a need felt, a compliance with the parent. And I can say that as far as I'm able to describe my own experiencing hypnosis many, many years ago, that is the way you fell. If one feels relaxed, almost amused, that this is the thing to do. He wants me to do it. I know I don't have to, but why not. The fact is that one cannot feel otherwise. But that is the relationship. Exactly as I have felt it and as has been described by many of the others. There is this tremendous thirst for obedience. I think we may say that there is no use for hypnosis except in the medical field and as practiced by a physician or someone bound by the same principles and with the same knowledge. There is danger in hypnosis, great. It is not necessarily true that a patient is weakened, but it is true that more frequently one is hypnotized, more readily one is hypnotized. Number two, the more frequently one is hypnotized, the more readily one may undertake autosuggestion. And that I think is the most dangerous part of all. This is the type of hypnosis which is taught by so-called psychologists. And this is no reflection on real psychologists who practice this type of therapeutics that we have here. And who teach people autosuggestion. And it's an easy thing to teach and an easy thing to learn, particularly if you hypnotize them once yourself. In this stage, there can be great relief from any anxieties. The relief that one may get from a narcotic, from heroin, with the same need to resort to it in situations instead of solving them. The hypnosis should never be practiced except by a capable and conscientious individual with a great regard for the sanctity of his profession and of the human being. It is not to be feared, if it is feared. Now there are many things, techniques and things that can be done. The phenomena of regression as we use it in the practice of hypnosis psychiatry you know I cannot touch on now. Interesting phenomena in the experimental field. The induction of complexes. The induction of phenomena like slips of the tongue and so on, as a part of a conflict. Most interesting, I recommend you to Erickson's readings on that. And I might later be able to do a cult one or two. But in medicine, I think there are two areas. One in the field of general medicine and surgery or use in anesthesia. There is no question that hypnosis is an excellent form of producing anesthesia. It has some serious limitations. Number one, a good anesthesia, at least for major situation, one must be able to get the somnambulistic stage. That can be produced in only 20 percent of individuals as they are. It take time and is questionable whether a surgeon will be willing or able to take that time. Obstetrics is an area in which that can be done. A woman who was being seen over a period of nine months by an obstetrician could perhaps be induced, and this is being done in the work of Reed and others, Grantly Reed and others in childbirth without pain involves certain aspects of hypnosis and not full hypnosis. And with the time to give the induction to be prepared, it can be very useful. In dentistry I have used it, and it's rather remarkable. When they pull a tooth without any pain whatever, without bleeding and have perfectly comfortable time right after it afterwards. But as I say, the readiness of anesthetics and the quick activity of them without all the long preparation will probably prevent hypnosis as it originally did. Hypnosis was just coming in as a surgical anesthetic when ether came into being. And it was the ether that prevented hypnosis from becoming more widely recognized. You see I haven't gotten to Bridey Murphy. We'll have to leave that for the discussion there. This is a form of regression. All I will say about it that all the evidence, and Bridey Murphy isn't the only case. There is a case in this book Hypnosis and You in which a man was regressed, a woman was regressed 3,000 to the time when she was a princess in Egypt. And used the Egyptian language which is confirmed by a student from Egypt. As I read the book, those were queer words to me. I'm not an Egyptologist, but they weren't Egyptian to me, and the names were not like Egyptian. And I'm just wondering. But I have serious doubts about it. The two other uses that are of tremendous experimental interest are sociological interests are those of Estabrooks who is suggesting the use of hypnosis in detection of crime. This brings up an important legal thing whether it's right to induce a state like this in an individual to get him to confess against himself and of course it will not be allowed by the law. In fact a case or two has already been adjudged. And this would not be an acceptable method. The other one of which we have seen a great example in the last two decades is the induction of crime by hypnosis by Hitler. It is not a technique. It is not a therapy. As Rosen says, and which I agree, one keeps a patient under hypnosis not by hypnosis.

[ Applause ]

>> We're sure sorry. We're sure sorry that we had canaries in the aerial there. That's an excellent picture, and it's too bad that you didn't get to see more of it. Now Dr. Masters suggests that it's gotten so late that there's hardly time for questions. I don't know what the final decision is. Why don't we have a few? There are men on the side. We get some of the more pointed and pressing questions. Had there been time I would have asked Dr. Simon whether or not this is true that the lawyers are having trouble since Bridey Murphy came out because people are changing their wills and leaving things to themselves? In other words, if you can't take it with you, there's a prospect you might come back and get some of it. Well these are getting a little bit. Alright, does it ever occur, Dr. Simon, or could it occur that the hypnotist be hypnotized by his patient? See what you can do with that one doctor.

>> Stand up straighter.

>> I've seen this happen almost to myself. He isn't really hypnotized by his patient, but in carrying out the process with a patient, he may carry out an auto suggestive process on himself and actually go into a trance. It has been reported, and I've nearly suffered it when you get too intense in the same thing.

>> Do you have many patients who were hurt by stage hypnotists?

>> No I haven't had any. As an actual fact, if these happen, they don't get into the literature which is my source of information. There are claims made, let me say on the other hand, I've heard of some stage hypnotists who've been hurt by them patients. If you call them patients. They're subjects or victims. In other words, this is an interesting thing that in the hypnotic state, the victim of the stage hypnotist finds himself unable to withstand the injunctions, particularly if they don't involve anything more serious and absurd things like running around barking like a dog. But I know of one or two instances where the stage hypnotist has carried this one to the extent where when the patient woke up he kept cracked him in the jaw for it, for making an absurdity of him.

>> How powerful is post-hypnotic suggestion? And too, what is the usual duration of effective post-hypnotic suggestion?

>> In many ways, post-hypnotic suggestion is even more powerful than the work in the trance itself. It seems to have a very compelling force, and it's interesting that you can get post-hypnotic suggestions carried out from a lighter stage of hypnosis, which the patient will obey even better than he will in the stage of hypnosis. There's no measure of just a standing except that the patient is very extremely uncomfortable if you've told him he must not smoke and then set up a conflict situation afterward as Erickson did where he's also told in the trance that he will want desperately to smoke. He will go through all kinds of machinations to smoke, and the match will break. He will drop it. Something will happen to the cigarette. It will get wet and so on and so on and so on. It's very compelling. It's like a compulsion as we know it in general psychiatry. The length it has been, I read in the literature that cases have been known to have gone for two years without revivification under post-hypnotic suggestion still carried out. The longest experience I've had by chance was I think I patient I mentioned to you who came back to the hospital two months after he had originally been hypnotized there and in which the hypnotic suggestion was that whenever I say sleep Joe, you'll immediately fall into a deep sleep and obey all of my commands. I had him in staff conference, and he had wanted to come back to the hospital, but he said he didn't want any more of that damned hypnosis. And I said look, all I ever did was say sleep Joe, and he immediately dropped to sleep facing me.

>> I think if we make them short we'll get to them.

>> Yeah, okay.

>> We're going to make them short. And I'm examining them closely so there's not a psychiatric mickey in any of these. Did I understand you to say that auto conditioning becomes a crutch? And do you use autohypnosis in the same sense as auto conditioning?

>> Well I don't know what is meant by auto conditioning. I think the terms are probably considered equivalent. I say that there is a tremendous danger, that no individual should have that type of external control over himself in an area where volition, decision, morality and everything else involved. And that it's better to be left at the mercy of your own self. If you need help, get it from someone else, from a doctor. And don't try to treat yourself. The doctor who treats himself has got a fool for a patient and another fool for a doctor.

>> We're really doing some business here. We're going to be here most of the night. Is it possible to cure severe addiction to smoking? Or to cure alcoholism by hypnosis?

>> I don't think it's possible to cure anything by hypnosis. As I mentioned, hypnosis is a background for treatment. Which makes treatment by the necessary psychotherapy perhaps easier and perhaps possible where not otherwise possible. I would never stop anyone from smoking or drinking by direct suggestion. But I would perhaps under hypnosis, treat him. And if I could keep him under treatment and know he is going to stay under a treatment as we could in the army, I might not even hesitate to take away a symptom. But to take away a symptom, not getting the underlying cause is most dangerous.

>> This seems like it's a little involved, this newspaper. We'll hold it and see. If a person to be hypnotized is only allowed a half normal sleep or four hours before, is it easier to hypnotize him in this half normal and half, you'll have to do the rest of it doctor. I can't.

>> Have normal and half trance. I don't understand what that would be. Half normal or half trance. A patient, the essential of hypnosis is relaxation. A person who is half normal asleep if I understand this, would be in a better relaxed state and might be easier to induce just as we call the state just before we fall asleep a hypnotic state where sensitivity and all is greater to certain phenomena. It might be. I don't think it matters too much whether the patient is asleep before you try it or not, if I get this question correctly. Alright.

>> Question of crime contravene, controversial. Professor Erickson says no crime can be committed against subject's character.

>> I think that's essentially what I said in my talk. That it will depend on what the potentiality of that individual is. Now, when you say no crime can be carried, forced against a subject's character, that's too often interpreted that no crime could ever be forced. I think it probably could be if the character of that individual permitted. And perhaps more readily.

>> How long does it take a person to be hypnotized who has shown resistance after five or six attempts?

>> After five or six attempts and no success at all of even getting in the first stage, I'd give up. In fact I'd give up sooner than that.

>> Is it of use in schizophrenia?

>> Very few people have been, schizophrenics have been hypnotized. Erickson is almost the only one who has worked in that area and has succeeded in hypnotizing mild schizophrenics. He did not do this for the purpose of treatment nor do I think it would be desirable where we have such a deep-seeded situation. There'd be great danger because since the hypnosis attacks the ego, there is tremendous danger of fragmentation where the ego is already so damaged as in schizophrenia. But he has used it for experimental purposes without danger to the patient and with full knowledge and precautions.

>> Now some of these we can't answer because I can't understand them unless you hypnotize me doctor. Can auto, can autohypnosis be brought to the somnambulistic state?

>> I think it can, yes.

>> That fixes that one. Is understanding the problem sufficient, or would hypnosis break the inability to proceed or an understanding?

>> I can't do much for that one.

>> Since the unfortunate fact is that we didn't get to hear the movie, it'd be fair to us to have another and louder showing.

>> May I answer that to say that there's nothing wrong with the movie. But the problem was the projection problem.

>> Now this interests me too, this question. Can hypnotism aid obese persons to lose weight doctor?

[ Inaudible Response ]

Please elaborate. Did you answer that?

>> No [inaudible]. The answer to that is the same as to many of these questions. I'm sorry. Is the same as to many of the questions. Obesity is not something in itself. It has a cause. You may have a glandular disorder. You may have any variety of disorders, to say nothing something even a pathological thing which causes a false swelling. You may have obesity from a false pregnancy, which might be helped by hypnosis for example. But obesity of a common type from overeating, compulsive eating, is not the obesity but the compulsive eating as a psychiatric disorder, an emotion disorder that needs treatment. Now whether or not hypnosis is used is to be determined by the doctor who does the treatment. However, it should not be used to just say don't eat. It'll work to say don't eat, and that patient will substitute likely for the eating a much more disastrous type of reaction. Unless the hypnosis is used to get at the cause, it should not be used at all.

>> The same thing, can hypnosis have any effect on a mentally retarded child?

>> You can't hypnotize a mentally retarded child. So it wouldn't have any effect.

>> Question of the name of a good hypnotist in New York, and what would you be put fully asleep in order to be hypnotized. I would take it that the name would come from the medical society, and the rest of it doctor would you.

>> Must you be put fully asleep in order to be hypnotized? In the lighter stages and so-called waking hypnosis, it is possible to get a mild hypnotic state without sleep. In fact no hypnotic state is sleep and it is sleep. If you understood my talk. It's, what the real point is that in the light stage of hypnosis, one can carry out forms of treatment.

>> Is there need for in medicine or dentistry for lay hypnotists and assist in preparing a patient for treatment?

>> Well I would say that in medicine and dentistry, the use of a, shall we say, hypnotic technician might be useful. Certainly not in the area of psychiatry. If there's going to be a hypnotist, it should be the man who is doing the treatment, the only person. In surgery and in dentistry, conceivably an expert who will do it only for this and under the supervision of the operator might be acceptable.

>> Please elaborate on pain sensations as under hypnosis.

>> I don't think time will permit an elaboration. I can only say that the situation in hypnosis is somewhat akin to that where you'd have a lobotomy where the patient feels pain, but doesn't bother him. The question does the patient feel pain or doesn't he under hypnosis, does he feel excessive pain? This is what he believes. He believes, he is told that he is to feel pain. As far as he's concerned he feels it. But the pathology is not taking place. Work has been done in electroencephalogy to see if there are pain impulses, actually passing through and affecting the brain waves. There's no agreement on that There are arguments on both sides. I don't, it would take much too long to try to go into the whole physiology of pain to show what hypnosis, hypnosis acts on what you think about pain, not on the phenomenology of pain. Not on the nerve endings or anything like that. If you think, you are made to feel nothing hurts, it doesn't hurt. And by the way, a mother does that when she soothes a child. The child gets hurts and momma says I'll kiss it. The laying on of lips instead of hands, and I'll make it well. That's a little mild form of hypnosis, and the transference relationship is the same. The child has implicit confidence and [inaudible] the mother. The pain goes away. Now what has she done? Just what the hypnotist does.

>> Can a patient be hypnotized out of arthritis? I imagine that's the same as the other.

>> It's one of the 27 on the list. Arthritis is a disease of the joints. Pains in the joints is something else. One may have pain in the joints but not disease. Maybe an emotional situation. The same thing applies as I've said about all emotional disorders. If that is true, there's an underlying cause which requires the patient to use the joints as a focus for his distress. You've got to get at that cause. Telling him his joints don't hurt will work for a time. It's easy enough to stop it from hurting, but the price may be infinitely greater.

>> Now doctor, despite what you said, as I used to say on the radio, I have a lady in the gallery who says is not hypnosis essentially a surrender of the will and hence undesirable particularly if repeated?

>> Well we're going to get into the semantics of will and all of that. Yes in terms of what I said about ego, it is a submission and a surrender to recognize and respected, revered, all feared, higher power, the hypnotist. I see no serious difference between and going to the doctor of your choice. You surrender yourself to his ministrations if you've got any sense. Or leave him and get somebody else. So whether this is a technique that can be used to help, then use it. Why fear this threat of will. I think too much is made of this kind of thing. Provided of course, this person is a professional person with the integrity that belongs with it.

>> Now here's a child of seven that has temper fits and tantrums. Should the parents do the best they can and wait for him to grow out of it? Or shall they seek the advice of a psychiatrist? If so, where can poor people turn to? Over please. Can an ugly disposition in an individual be cured by hypnosis? The first one, the child of seven.

>> To the last one, the answer is still the same. Why the ugly disposition. Let's find out why that is. And for the child of seven, with temper tantrums [inaudible] in this extraordinarily general sense, why the problem is obvious. That is to seek the help where he can get it and where it belongs. And I would suppose a psychiatrist at a child guidance clinic or family counselor at least to begin with would help. Where can poor people get this in New York? I am unable to answer. It's hard for rich people to get it today, as well as poor. There is a shortage of psychiatrists. There are outpatients, there are clinics. Child guidance centers and so on. I think again as Dr. Brayson said, if you ask the Academy here, they will probably be able to help you.

>> The Academy or the County Medical Society, and I am sure you can get a list of them. I'm sorry you didn't answer that second question about an ugly disposition. My wife would have been, she would have been interested. How is waking suggestion connected with autosuggestion?

>> Well, the waking suggestion, the process that Coue advocated was without putting the patient in a trance, to repeat a suggestion so frequently that it took, which can be the case. And it can be done by yourself, and there for it's autosuggestion when it's done that way. It may be done by someone else.

>> Please give the most helpful current bibliography on medical hypnosis. That will take a while. It will be published I take it, the bibliography along with the articles?

>> Well I can add a bibliography to it if [inaudible].

>> Have you anything to say about the phenomenon of so-called clairvoyants under hypnosis?

>> Well clairvoyants, I'm not sure what you mean. I suppose you're getting at telepathy, transference of thought. Insight into the past, the future. All of those things however, come under the phenomenon of mediumism, to which I alluded and to which there is a self-hypnosis by the medium. And a heightening of perceptions and so on to the extent of being able to use under this intensely concentrated state, all the facilities, the capabilities that they have. All the senses are definitely sharpened up. They're not [inaudible] beyond capability. Now as to whether telepathy transfer of thought takes place, I don't believe. You've got to understand that in a hypnotic state, the patient is extremely susceptible to everything. One patient I recall was reading cards in a clairvoyant state in a sort of phenomenon that Ryan, as most of you read about, done by J.B. Ryan. And was selecting cards almost without failure. And it was discovered that the cords were being reflected into the cornea of the hypnotist, a tiny little thing, and that patient would see them and read them in the hypnotist's eyes.

>> Well doctor on that delightful note, we will thank you very much. We've been wigwagged, and we've gone too late. Our appreciating to you, thank you.

>> May I make an announcement? Don't forget that instead of February 6th, February 13th, Dr. William H. Sebel [phonetic] will talk on food and civilization. I want to thank you very much for your patience. And I want to tell Dr. Simon that the hypnotist can help an ugly disposition. I think we all felt pretty ugly in terms of that movie. But with the short snappy answers we're in a better frame of mind. [M1]