By Clarissa Sosin and Kate Ryan

Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers have made 150 arrests in and around New York state courthouses since President Trump took office, their targets ranging from a traffic court in upstate Onondoga County to a family court in Brooklyn, according to records compiled by immigrant advocates.

The vast bulk of these arrests have occurred in New York City, where federal agents have repeatedly clashed with public defense lawyers who have argued that seizure of their clients both disrupts due process and threatens public safety.

The public defenders have held protests in Brooklyn and Queens this week, drawing criticism from court administrators for causing disruptions of their own. But Scott Hechinger, a lawyer for Brooklyn defenders, says the aggressive activity by ICE demands a response.

“It's just been more brazen,” said Hechinger, prior to this week’s protests. “We're on edge as public defenders, as advocates, and I think our clients and their communities are as well.”

Of ICE’s arrests in the city, the records show, almost half have taken place in Brooklyn, where a walkout by defense attorneys last fall was followed by a mass protest on the steps of Borough Hall.

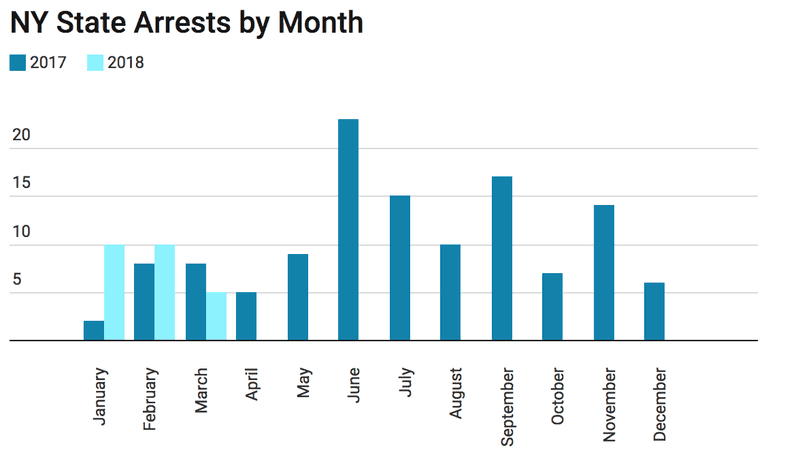

Despite those confrontations, the federal agency shows no signs of slowing down. Records given to the non-profit Immigrant Defense Project by lawyers and family members of detained individuals show that ICE officers made 20 arrests in January and February this year at courthouses in New York state, nine of them in Brooklyn. That is double the pace of arrests reported to IDP for the same two months last year. In 2016, IDP reported 11 arrests for the entire year. These reported arrests occurred inside the courthouse, just outside, or within a few blocks, said Lee Wang a senior staff attorney for IDP.

“I think it's important for people to understand that even when an arrest happens outside of a courthouse, ICE agents are still going inside the courthouse to find and identify the people they're going after,” said Wang who focuses on the criminal justice system’s effect on immigrant families for IDP.

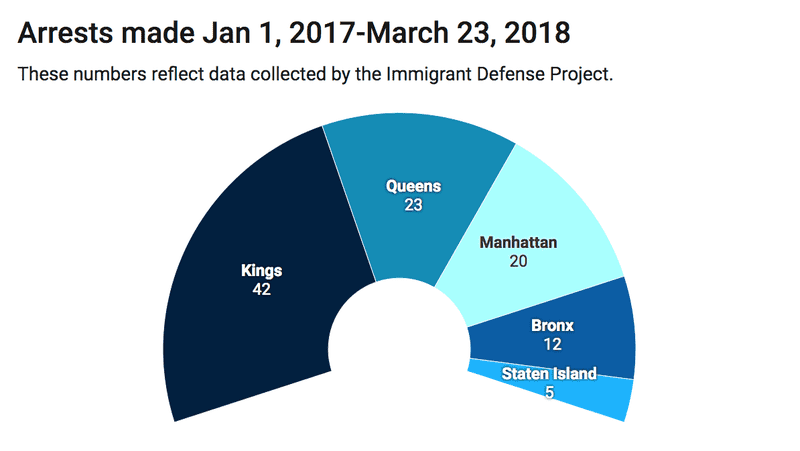

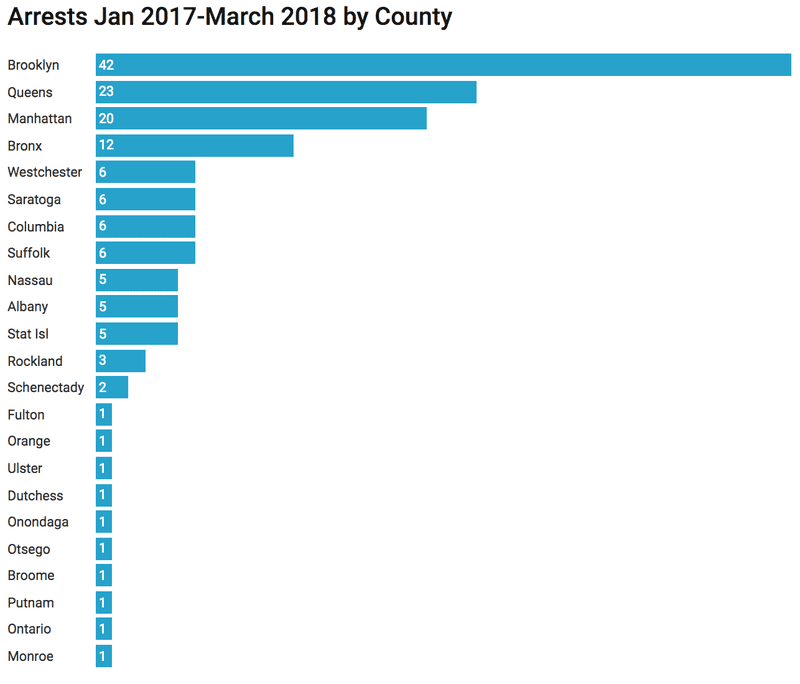

The data shows that between January 2017, when Trump took office, and March 2018, ICE made 42 arrests in and just outside Brooklyn’s courts. The courthouse with the second highest number was Queens, where agents arrested 23 people, followed by Manhattan with 20 and the Bronx with 12. Just five arrests have been carried out in Staten Island.

Outside the city, the most arrests have been in Suffolk, Westchester, Columbia, and Saratoga counties, where authorities have made six arrests in and around a courthouse in each county over the past 15 months.

Records also show that the arrests spiked in June, when 23 people were detained at the state’s courthouses.

ICE officials declined to comment on IDP’s data. When asked for their own records of courthouse arrests, an ICE representative said, “We don't keep stats to that detail.”

In January, ICE published its policies and procedures regarding arrests in courthouses.

Officials cited the refusal of “some law enforcement agencies” to “honor detainers or limit ICE’s access to their detention facilities” as a reason for making arrests at courthouses. They added that courthouse security ensures “safety risks” are “substantially diminished.”

Wang said the agency’s use of courthouse arrests even in more cooperative upstate counties indicates that ICE prefers the tactic.

“This is not a place of last resort for them,” said Wang. “This is a place of first resort.”

The January policy memo says agents enter courthouses to make arrests when they have “information that leads them to believe the targeted aliens are present at that specific location.”

It says the agency targets “aliens with criminal convictions, gang members, national security or public safety threats” as well as those “who have been ordered removed from the United States but have failed to depart.”

ICE officials declined further comment on their methodology for tracking “targets” to the courthouse.

Shawn Blumberg, another attorney with Brooklyn Defenders, said that most individuals were arrested by ICE in criminal court, where they were facing misdemeanor charges and minor violations. Arrests have also taken place in family and traffic court, and even a court in Queens that handles human trafficking cases.

“It’s low hanging fruit,” said Blumberg. “They clearly have a blank check and they clearly are going after anyone and anybody that they can.”

Blumberg and other advocates and defense attorneys say there is little information about the strategies ICE uses to determine when non-citizens are present in courthouses.

One piece of the puzzle emerged from a study published in September 2017 by the National Immigration Law Center which identified the various databases that allow for cross referencing an individual’s civil, immigration, and criminal records between state, local, and federal agencies.

One such database is Secure Communities, a program run by the Department of Homeland Security that was revived by President Trump just four days after taking office.

The “Secure Communities” program transfers data collected at the point of an arrest, including fingerprints and criminal records, to an FBI database. Those records are then forwarded to the Department of Homeland Security where, if a match is spotted with an individual, a red flag goes up.

“All of that data-mining is practically instantaneous,” said Wang, of the Immigrant Defense Project. “It’s a lot easier than doing a pre-dawn raid on someone’s house.”

In April 2017, the Office of Court Administration, which oversees New York’s courts, updated its policies about courthouse arrests. The policies state that any federal agent who enters a courthouse without a warrant with the intent to arrest an individual, must report their presence to a uniformed court official. That information must then be relayed to the judge presiding over the case involving the defendant. Notification of a defense attorney about ICE’s presence in the court is at the judge’s discretion.

ICE officials said that agents can make arrests with both administrative and criminal arrest warrants, but both defense attorneys and court officers have said that ICE agents usually don’t show up with a warrant.

Defense lawyers say the OCA’s policy does not go far enough. They say it deprives them of the chance to notify their clients of their rights or inform their family of a possible arrest.

Thanks to ICE’s active presence in Brooklyn’s courts, tensions have also flared between defense lawyers and court officers who maintain security in the courts.

“We’ve heard instances of court officers helping ICE to identify individuals, point them out, delaying the calling of their cases to make sure ICE could be there to pick someone up,” said Wang. “In some cases we’ve heard of court officers physically assisting in arrests, physically preventing defense attorneys from reaching their clients.”

Wang said there were a number of instances in which court officers allowed ICE agents access to restricted areas of Brooklyn courts.

Dennis Quirk, the president of the NYS Court Officers’ Union, said court officers are caught between pressure from ICE to make sure arrests happen in an orderly manner and pressure from attorneys who say their clients’ rights to due process are being obstructed.

Quirk adamantly denied that officers were alerting the federal agents to cases involving undocumented residents.

“We’re not tipping ICE off, and there’s nothing in it for us,” said Quirk.

The union leader said that ICE officers appear to know exactly which courtroom they are going to once they enter the building. If they ask for assistance, he said, the agents are directed to the clerk’s office for directions.

“There have been some times when they come to the courthouse and they’re just looking,” said Quirk. “They’re looking to see if somebody looks to them like they’re an illegal, and then they grab them.”

He said that any law enforcement officer, be it out-of-state police, NYPD or ICE, can make an arrest in the courthouse.

“If they’re there looking for somebody, it’s a public building,” said Quirk. “We can control actions inside a courtroom, but what happens in the hallways of the building or the lobby of the building, it’s a public building. We have no control over that.”

Quirk added that court officers only intervene if there is a physical altercation.

“When you start with these little confrontations in the hallway, there’s always the possibility someone’s going to get smacked or pushed and hit their head on the marble floor and get a serious injury,” he said. Quirk said his officers have received injuries in altercations that began when lawyers in Brooklyn advised their clients to flee.

Attorneys from Legal Aid, the city’s largest public defense provider, denied the claim.

Anthony Posada, the supervising attorney of Legal Aid’s Community Justice Unit, said lawyers who attempt to hide clients or prevent ICE from arresting them can be legally charged for harboring a fugitive.

“All we’re looking to do is protect our clients, and we ourselves are beholden to the law, said Posada.

Casey Dalporto, a Legal Aid attorney in the Bronx, where attorneys have staged several walkouts, said it is an uneven contest.

“At the end of the day they are the muscle, they have the guns and they take the client,” she said.

Part of NYC/45: Tracking the Trump Effect in New York. A team of students at the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism investigate the impact of President Trump’s policies on his home state and town.