The Brian Lehrer Show

The Brian Lehrer Show

Imani Perry's Journey Across the American South

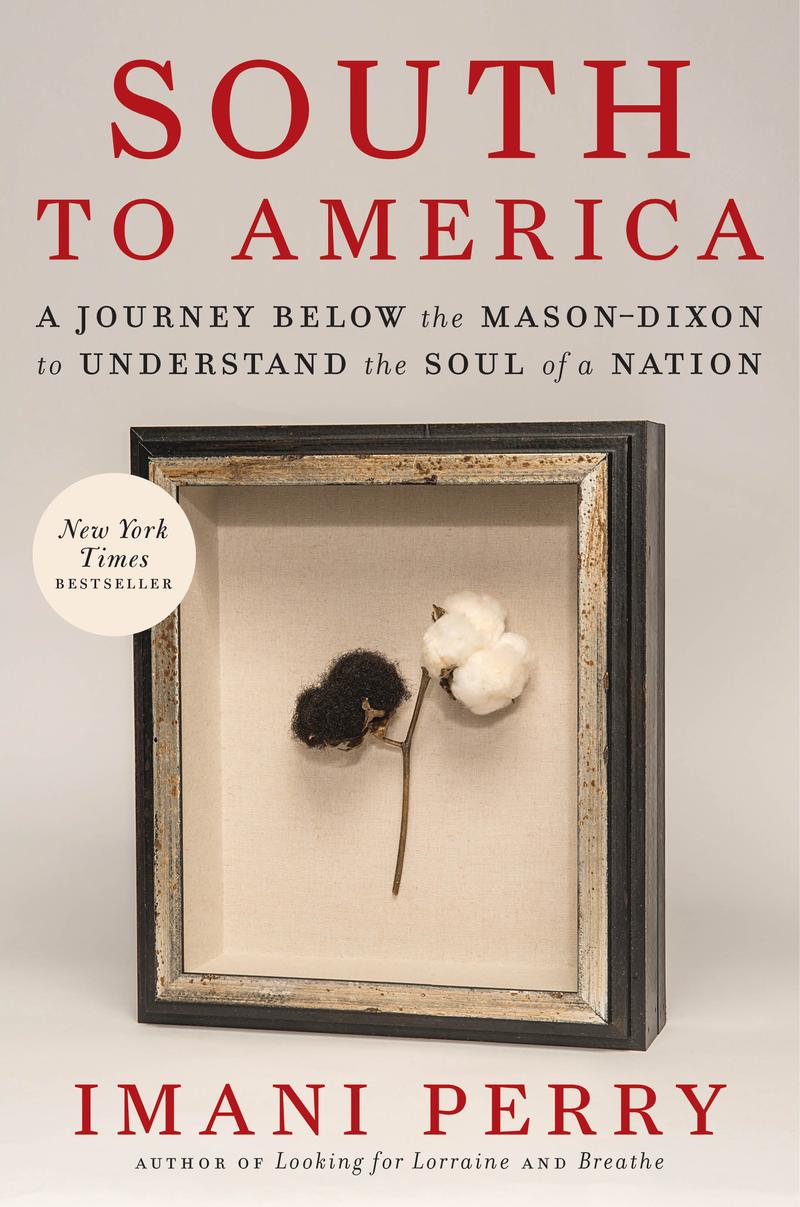

( Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers / Courtesy of the publisher )

Imani Perry, professor of African American Studies at Princeton University and the author of South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon to Understand the Soul of a Nation (Ecco, 2022), shares the insights she gleaned about U.S. history and culture from her travels in the South.

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone. Mayor Adams is coming up around 11:30. Right now, the American story is also resoundingly the story of the South. So much of the making of this country took place below the Mason-Dixon line where our nation's capital, don't forget, the symbol of which was built on the backs of enslaved people, remains. Now we'll talk about the South's message to America and what we can learn about the country's history from a closer look at the experiences of Black Americans who call the South home.

Joining us in just a minute will be Imani Perry, professor of African American Studies at Princeton. Her new book is called South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon line to Understand the Soul of a Nation, its history, and its contemporary realities. We want to open up the phones for some of your stories, 212-433-WNYC. If you're a listener with ties to the South, what's your relationship to the South and to the history of the South? 212-433-WNYC. Particularly, if you're a Black American who calls the South home or whose familial routes lie down there, well, what is your relationship to the South historically or today? 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692, or you can Tweet @BrianLehrer.

What a tortured history people who live in the North feel that the country has with the South, the Confederacy, obviously, and then even today. That's where the lines of the culture war are also drawn in significant terms. Not entirely, I mean, there's South New York City, Staten Island, which voted even in a higher percentage for Donald Trump than Texas did, but the Mason-Dixon line in a certain respect means something even in 2022. Give us a call and talk about your family's relationship to that historically and today. 212-433-WNYC. 212-433-9692. Again, Professor Imani Perry from Princeton has her new book called South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon line to Understand the Soul of a Nation. Professor Perry, thanks so much for joining us. Welcome to WNYC today.

Imani Perry: Thank you for having me.

Brian Lehrer: You included a disclaimer that said, "Please remember, while this book is not a history, it's a true story." How do you distinguish between a true story and a history for the purposes of this work?

Imani Perry: Sure. History, it's a form. It has a very particular method that's disciplinary that goes and tells a coherent storyline. A story, I think, in this respect, is much more invitation to walk with me. I'm asking readers to be present with me in these places, to understand them as places that have layered meaning, that are ambiguous, that are complicated. I'm not telling readers what to think or even making a particular argument, but rather, it's an invitation. It's an exposé of sorts. It's wanting to encourage a discussion about the centrality of this place in our history and in our culture.

Brian Lehrer: Some of this I see is personal for you. Do you want to tell the listeners anything about your own family routes in the South and how it related to the bigger picture?

Imani Perry: Yes. I was born in Birmingham, Alabama. I locate myself nine years after the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, three miles away was where I was born. Most of my family has always lived in the South and continues to. I migrated North as a small child but went back and forth my entire life.

I also travel to other parts of the South regularly in addition to preparations for this book. It is home, but a home in which I describe myself, in some sense, as an exile from. I have seen it both from the inside and been very aware of the way people in other regions, especially in the Northeast, see the South. It's that insider-outsider perspective that I bring to bear on the book.

Brian Lehrer: You open with a story of a man named Shields Green, who is known as the Emperor of New York. Who was Shields Green and why did you start a book about the South with him?

Imani Perry: I started the book in West Virginia, and particularly in Harpers Ferry, and he was a member of John Brown's group that sought to emancipate Black people from slavery and initiate what would be a Civil War. They failed ultimately, but John Brown's raid was an important event as a precursor to the Civil War. I wanted to talk about someone like him because West Virginia is this interesting place that was seceded from Virginia in the context of the Civil War, ultimately, because it was anti-slavery and then becomes associated with a Neo-Confederacy later.

Here we have this figure who is from South Carolina but is referred to as the Emperor of New York and is a member of John Brown's raid and didn't leave records because he was not literate and is this story figure in history. I just wanted people to begin in a place of the ambiguity about the story of the country, where it begins, what regions were pro and anti-slavery, because I wanted a kind of disorientation, in a sense. I want people to encounter it a fresh way because we operate with all of these stereotypes, particularly at the South of all the regions. It was meaningful to me to put us in places and with people who we don't ordinarily think about.

Brian Lehrer: Let's take a phone call and hear a story from Sharon in Harlem. Sharon, you're on WNYC with Princeton's Imani Perry. Hi, Sharon.

Sharon: Good morning. Good morning to you, guest, and good morning, Brian. Second-time caller. My connection is very close to the South. My father grew up in a segregated Alabama, Mobile, Alabama, Greenville. There were his grandfather-- He wanted to be like his grandfather, who had 11 children, so he had 11 children. I'm number 10. My father often talked about the experiences growing up in the segregated South. He told of a particular experience where he was a child and the Ku Klux Klan were marching through the streets, through the town.

As a child, being curious, he leaned over to get a better peek, but his foot slipped off the curb and he fell into the passes of the protestors, the folks marching, and a white man slapped him. That was his experience that he'd never forgot and one of the things he vowed that he wanted a better life for himself, that he could not live in this segregated South, but he had family and aunties and all that, so he'd go back and forth, he'd let some of my brothers and sisters to go down to visit. I'd never got the chance to, unfortunately, but I know the stories.

I have a tintype of my grandmother who-- I could see all the ways we related, but even just the whole thing about family, that deep connection. That is what we took from the South. That is what we carry even now with my own children, with my own grandchildren. We can tell stories, tell the stories of our grandparents, and tell the story of his grandmother. He was a free-born slave. His father was a free-born slave. I didn't understand, I saw it in the books, but that 13th, 14th, and 15th child were free-born slaves. My father always says-- he says, "I'm a child of a free-born slave." That's my connection to the South. Thank you so much for letting me share that story.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you. Please call a third time, Sharon. Wow. Free-born slave is probably a term that a lot of people have never heard.

Imani Perry: Yes. Also, I think there's something that the caller said that is so resonant, which is the significance of family, which is in part and particularly for Black Southerners because of how vulnerable the structure of family was historically. If you could not claim possession of your children and you did not, you weren't sure whether or not your children would be sold away or treated violently or the like. There is a culture that holds very tightly to family.

I also think this point is interesting, which is about what the South means for migrants because so often for the South, for people who are from Great Migration families, the South that they think about is that one from multiple generations ago, but for people like me, and really, the majority of African Americans who still live in the South, there has never been a moment in history and of this country where the majority of Black people were anywhere but the south. [chuckles]

There's this past vantage point and then there's the present South. There's also the truth that many migrants who left the South, either for work or as a result of violence encountered incredibly violent Northern cities, particularly in the Midwest, suddenly it's called the north everything. It's not the south for all the different regions, but there's a lot of racial violence. I think that's the other thing too that's really important to keep in mind.

Brian Lehrer: Let's take another call. Sam in Kew Gardens in Queens, you are on WNYC with Imani Perry from Princeton. Hi, Sam.

Sam: Hi. Is that me?

Brian Lehrer: Yes. That's you.

Imani Perry: Hi.

Sam: [laughs] Good morning, I'm Sam. This is my second time calling, Brian. The first time I called was when you had the emergency room doctor offering an explanation as to why African Americans avoided the COVID vaccine because of suspicions of doctors. I had 30 seconds at the end of the show.

Brian Lehrer: Well, I'm glad you're getting a second shot. You can have more than 30 seconds today.

Sam: Well, I mentioned to the screener that it wasn't really clear to me what you were looking for, except that I grew up in South Carolina. I have lived a year in West Virginia and 10 or more years in Alabama before coming to the Northeast for grad school. I've been in New York City since May of '93, but I still have ties to the south. I still go there as often as I can. I mentioned to the caller that I could tell the story about having a white lady come to my rescue when I fell off a bike as a child if that was of any interest or whatever.

Brian Lehrer: You've mentioned to my screener, if I got the screener message right, that you've gotten into many arguments with people who presume to know the South without ever being there. What's an example of such an argument if I have that right?

Sam: It wasn't many, but it was a couple of doozies. One was in San Francisco and one was here in New York. Basically, I've had people who freely admit to never having been to the South or except for maybe Florida or having spent any significant time there, who nevertheless will argue with me, a Black person who grew up in the South, about what it was like to be a Black person in the South. These were neither Black people nor had they been to the South, yet they presumed to argue with me about what it was like to be a Black person in the South without apparently realizing how insulting it is that they think that they know better what my experience is than I do.

Brian Lehrer: What was it about your experience or one thing about your experience in the South that you think people didn't hear easily?

Sam: Well, they think there are strong prejudices about the South, about what it's like, what it's like for Black people in the South. One thing that I would say to people is that in my experience, and in the experience of my family, class was maybe more of an important thing than race and that we were, I guess, near the bottom of the middle class. I'd never considered us poor, but if we were middle class, we were lower-middle class. Both my parents worked outside of the home in factory jobs. We had enough money to get by. They had enough money to build and buy a new house and all of that. We never wanted for anything. As a child, I never considered us as anywhere approaching being needy. Although I did know people who were needy.

Brian Lehrer: Sam, I'm going to leave it there and get some thoughts from Professor Perry. Thank you, and please call us again. Some interesting things.

Imani Perry: This is such a great set of things that Sam just said. One, absolutely there are all of these stereotypes where people presume to know the south. This is part of why I quote a man in Appalachia saying it's important to be humble. That don't act as though everything. He mentioned being helped by a white woman when he fell off his bike as a kid, there's so much intimacy across racial lines in the South that it's relatively rare in Northern cities that I think people often miss. There is both intimacy and racism simultaneously. There's closeness. People live in much less segregated communities on average.

Brian Lehrer: Jimmy Carter has talked about that.

Imani Perry: Yes. Oh no, it's absolutely true. I think also a really important point about the significance of class and not just the racial logics. Similarly, we came North for my mother to go to graduate school, and so that is a distinct perspective, in part, because there's not-- I think people think that Black people were all trying to escape this out. [chuckles] That's just not true. People often traveled for work or for opportunity, but still, feel as though that home and actually have either preference or deep emotional ties for the south. I think that's an important corrective because the projection of racism on the south allows for other regions of the country to feel as though they are absolved of the inequality that exists everywhere.

Brian Lehrer: Bringing this even more toward the present, it's been 50 years already, I think it would be accurate to say, since after the great migration of Black people from the South to the North in the United States. There's been a reverse great migration or reverse some level of migration that's seen many Black Americans leave the north for Southern cities and Southern suburbs.

Imani Perry: Absolutely. I think part of that is because of a lower cost of living, a perception that there's a higher quality of life in Southern cities, that it's this easier pace of living. It's also important to note that as an addition to the great migration story, the great migration story is also a story about the great migration of White Southerners who were also seeking labor opportunities. As people have found themselves precariously situated, it's always the case that people move when they are looking for more stable living. This is the history of the movement, I think, is the history of the country at large and notably more White Southerners proportionately migrated in the great migration than Black Southerners did.

Brian Lehrer: Do you think that the South, and I guess by that I mean the White South, has dealt more directly and more effectively with racism than maybe the White North, because the White North while having lots of racism in it comforted itself with the fact that Jim Crowe didn't officially exist here and slavery didn't officially exist here?

Imani Perry: Right. It did but it was abolished earlier, and not legal Jim Crow, but certainly enforced segregation and practice in so many places.

Brian Lehrer: That's the distinction.

Imani Perry: Yes. Right. I don't know. I don't think it's fair to make a overarching assessment. I will say that the larger social and civic and legal impact of the civil rights movement is very apparent. For example, schools in Southern cities are much less segregated than in New York, and rates of high school graduation are greater for Black people in Southern cities than they are in New York, for example. I do think that-- and at the same time, there is a distancing from those legacies in the sense of what is the accountability that is required.

I would want to go back to something you said earlier about the political landscape because the confusion that's created by the red state blue state map thing, and you mentioned [chuckles] Staten Island, there's this perception that certain places are Democrats and certain places are Republican and relatively conservative. The whole country is purple and there are so many blue counties in the south and cities and towns, and so one of the ways that we don't deal with the complexity of our political landscape is we focus on the color of the states on the map, as opposed to the landscape, and who votes in which way and why and how are they moved about politically? The south has this cultural power because of Southern elite politicians, but their message resonates far beyond the region, and that is important to attend to.

Brian Lehrer: There we will leave it for today as I think we have the mayor standing by now. With Imani Perry, professor of African American studies at Princeton University, her new book is South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon Line to Understand the Soul of a nation. Great conversation. We look forward to having you back.

Imani Perry: Thank you so much.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.