For New Jersey Jails, Suicides and Overdoses, but Little Oversight

By one count, New Jersey's county jails have the highest rate of deaths in custody of the 30 largest systems in the nation.

David Acosta was at home on a Sunday morning in January when he got the call from a friend, a corrections officer at the Hudson County Correctional Facility, who told him that something bad had happened to his sister.

“I said, ‘I know, she’s locked up,’ ” Acosta remembered. “He said, ‘No, it’s a little worse.’ ”

Guards found Cynthia Acosta, 34, hanging from torn bed sheets tied to an overturned bunk. She was the third of six deaths that occured at the Kearny facility between June 2017 and March 2018, and one of dozens of suicides that occurred over the last several years at the state’s county jails.

The exact number of deaths at New Jersey jails are difficult to count. An examination of public records found wide disparities in the statistics that counties maintain and what they provide to the state and federal governments. In some counties, the month-by-month death numbers listed in annual state inspection reports do not add up to the yearly totals in those very same reports.

There are jails in 20 of New Jersey's 21 counties. They operate with little oversight from the state Department of Corrections, which has a patchwork system of rules and no consistent system for investigating deaths. In Hudson County, 17 deaths were recorded at the jail since 2013, but officials could only locate incident reports on six.

What is clear is that, according to the latest figures available from the U.S. Department of Justice, New Jersey jails have the highest per-capita death rate among the 30 states with the largest jail populations. And suicides committed by those suffering from untreated drug addiction and mental illness are a big driver of that number.

The rate of suicide in New Jersey jails rose an average of fifty-five percent each year between 2012 and 2016, according to documents provided by officials in the 15 counties who responded to our records request.

Suicides make up as much as a third of all jail deaths. But with the exception of Hudson County, where officials recently increased spending on mental health and stepped up screenings as part of the intake process for prisoners, these deaths have garnered little attention from the state.

A Death in Hudson County

Cynthia Acosta had a history of drug abuse, but in the weeks leading up to her arrest and suicide she was getting help. She admitted herself to an inpatient mental health program at Christ Hospital in Jersey City, where she was diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. A prescription for psychiatric medication helped to stabilize her.

“I noticed her changing throughout those days when she was taking the medication,” said David Acosta, who was putting his sister up at his home at the time.

At this point she was feeling ready to find her own place, but to qualify for housing assistance she needed a copy of her identification records. So she drove to a government office in Hoboken, despite having a suspended driver’s license. North Bergen police officers pulled her over and arrested her for past traffic violations. She was booked at the Hudson County Correctional Facility and housed in the women’s combined medical and mental health unit — a small, windowless, triangle-shaped room bordered by three cells, a shower and a nurses’ station.

David Acosta said his sister’s new medication was left in her vehicle when she was arrested. Three days later, she was dead.

Cynthia Acosta was the youngest of five. “She just brought life to everybody,” her brother said. “That’s who she was.”

He blames his sister’s death on poor monitoring in the Hudson County jail medical unit. “This could have been prevented,” he said.

Hudson County Correctional Facility Director Ronald Edwards, the third director of the jail in two years, acknowledged that the jail’s nurses didn’t have enough training and resources to deal with mental health issues. But he said inmates were appropriately monitored.

“Those six deaths, they all have my name attached. That’s a heavy weight,” he said. “It was my facility and my community and these people’s relatives that had brought this crisis to the forefront.“

After the string of deaths, cells at the jails were reconfigured to prevent hangings. Hudson County is also building new multimillion-dollar health units with one of the most progressive medical and mental health programs in the state.

Seventy-two percent of the people in the Hudson County jail are dealing with mental illness, drug addiction or, like Acosta, both, according to jail officials. New Jersey, like most other states, spent decades moving mentally ill people out of decrepit institutions. But, also like most other states, New Jersey never replaced them with other service options. So jails became the de facto mental health care providers.

Health Care Faulted

While incomplete and inconsistent record keeping makes it hard to pinpoint the causes behind all of the jail deaths, experts point to problems with jail health care as a common denominator. Of the 10 jails with the highest death rates in New Jersey, eight contract out their medical services to one for-profit provider, CFG Health Systems, based in Burlington County.

CFG doesn’t release information on specific cases. A company spokeswoman said it consistently gives inmates a high level of care.

But a nurse practitioner who used to work in New Jersey jails and is familiar with CFG’s practices said the system rewards companies that provide less care. Since the medical contractor gets a flat rate per jail, she said, increased services means the less profit for the company.

“The more patients I saw, then the more orders for medications there were, the more referrals to psychology there were. So it’s more work for everybody,” said the nurse, who asked not to be identified because she still works in the corrections field and feared retribution. She said she flagged one prisoner who later committed suicide for mental health problems, but her colleagues failed to follow up.

The contracts for health care at jails are awarded by the elected county officials. Since 2001, CFG and its executives have given more than $400,000 to New Jersey politicians. About $100,000 of that went to party organizations and officials in Camden County, where CFG operates a medical unit at the local jail.

Daniel Valdez, who struggled with addiction, was 33 when he killed himself there in 2016. He was one of 11 people who died under authority of the Camden County Department of Corrections that year. Two died in the jail, and nine people who were on probation.

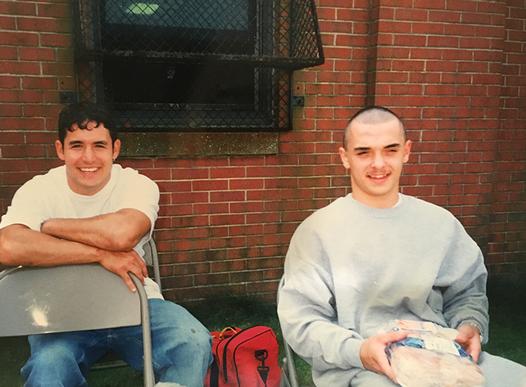

Valdez’s friend, Mike Sorrentino, also struggled with addiction. He was actually at the jail on a possession charge the night Valdez came in for the last time, and he shared a cell in the intake area with his friend.

Over the next four days, Sorrentino said he kept watch as Valdez went through the withdrawal routine: Visits to the nurse’s station at the start and end of each day. On the first morning, Valdez took a regimen of withdrawal meds — vitamins, and librium to calm him down. But he vomited the pills.

“[The nurse] said ‘Oh well, that would have helped him.’ Oh well, they can’t do nothing about it,” Sorrentino said. “Now at this point he looked like a good wind could have picked him up and took him away.”

On the third morning, Valdez fainted and knocked his head against a brick wall. Sorrentino said the nurse alleged that Valdez was faking his injury. On the fourth day, Valdez fainted again while the nurse took his blood pressure.

“She looked me right in the eye and said ‘If he's not bleeding or he's not dead, there's nothing we can do for him,’” Sorrentino said. Later that night, Sorrentino went to Valdez’s cell to give him a Snickers bar. He found Valdez hanging from a bedsheet tied to the upper bunk.

A Camden County spokesman, Dan Keashen, said nurses did do their job, and that Valdez got the right medication and monitoring. He said an internal investigation found that Valdez’s other cellmate didn’t corroborate Sorrentino’s allegations. Keashen also said the county contracts with a monitor who oversees CFG’s performance.

Gaps in Oversight

But Jeanne LoCicero, the legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union of New Jersey, which is seeking documents from jails to try to hold officials accountable, said there’s little incentive for stricter monitoring of CFG’s performance. She points to online photo galleries of CFG executives throwing fundraisers for the New Jersey County Jails Wardens Association.

“Once the counties enter these contracts, we don't know if they're auditing the contracts and making sure that they're getting what they asked the provider to do,” she said. “When different places have different numbers of something so critical and so certain as a death, it seems that that we know we have a broken oversight system.”

Camden County jail director David Owens said his jail administrators regularly meet with CFG Health Systems to discuss standards of care. About 60 percent of his jail’s population have drug and alcohol problems, he said.

“I'm sensitive to the complaints,” he said. “We are responsive as we possibly can be to them. And we are concerned that the individuals committed to this facility have the best medical care possible.”

The state Department of Corrections conducts annual inspections at the jails, checking off about 800 different standards. Over the last five years, 80 to 90 percent of the jails were listed as being in full compliance, records show — even if they failed to accurately report death totals.

“The state inspections are a joke,” said Robert Murie, who spent 28 years as a corrections officer at the Atlantic County Jail before he retired last year.

Murie said jail officials have ways of getting around state rules like the requirement that each inmate gets “25 square feet of unencumbered floor space.” In 2014, a state inspector marked Atlantic County as noncompliant for squeezing three inmates into two-person cells. So the next year, Murie said, the warden moved the overflow into a mental health holding area before state inspectors visited.

“State came,” Murie said. “They saw that the counts were correct. They left.” And right away, jail officials moved the inmates back to the crowded cells, he alleged.

Murie also said that jail officials fudged death totals by discharging inmates at risk of death to a hospital, so they wouldn’t be on the jail’s record.

Atlantic County officials denied all of Murie’s allegations.

But in Camden County, records show how a sick inmate was released just before he died, and another dying inmate received his discharge papers at the hospital. Those cases were not counted as jail deaths.

The state of New Jersey doesn’t publish summary statistics on county jail deaths. But a WNYC analysis of 80 recent death reports, obtained from the seven deadliest jails through public records requests, found that half of all inmate deaths, regardless of cause, happened within the first two weeks of admission. Female inmates were overrepresented in cases of suicide.

Marcus Hicks, the acting Commissioner of the state Department of Corrections, refused numerous requests for an interview. An agency spokeswoman said county jail deaths are a county issue. “Our role is to establish the standards,” said the spokeswoman, Alexandra Altman. “And it’s the role of the county to meet those standards.”

In contrast to New Jersey, New York’s Commission on Corrections is an independent body that investigates every death in local jails, with the power to interview employees, inmates and family members.

At the end of 2017, the New Jersey Department of Corrections announced they will keep more formal records of all jail deaths. But so far this year, the state has records on less than two-thirds of confirmed deaths in county jails.

Correction: This story has been updated to reflect that nine out of the 11 people who died under the authority of the Camden County Jail in 2016 were on probation, not parole.

For transcripts, see individual segment pages.