Candidates running for office are not usually across the ocean weeks before the election. But WNYC caught up with Rachel Freier, the Democratic nominee for civil court in southwest Brooklyn’s 5th Municipal District, by phone ... in Israel.

"I have a passion for law and fairness and standing up for what’s right, and I felt that that combination would really be ideal for a civil court judge," she said.

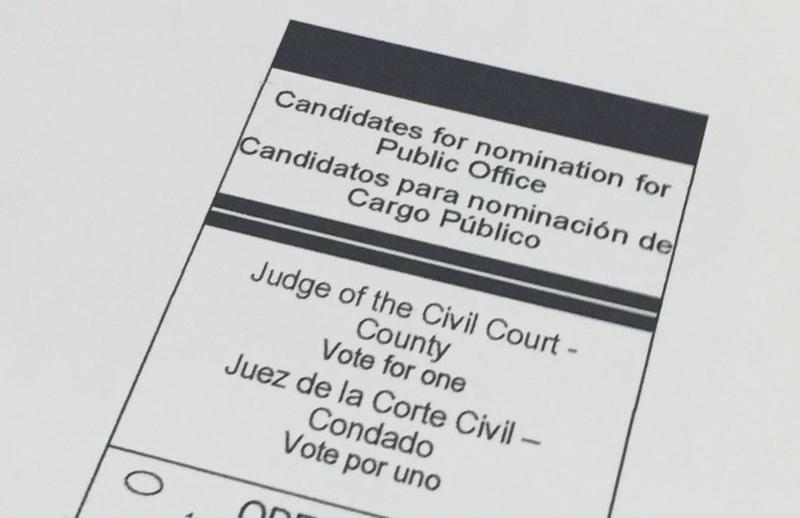

That Freier was abroad so close to the vote sums up the competition — or lack of it — in New York City’s judicial races. Most candidates are running unopposed. There are 46 judicial seats open, and just five of those races are contested.

Freier did have opponents in the primary: Jill Epstein, a law clerk, and Morton Avigdor, who, like Freier, is a Hasidic lawyer from Borough Park. A few weeks before the primary, the New York Daily News ran a story alleging Avigdor had failed to repay nearly half a million dollars from a client’s estate. He lost by a wide margin. But Avigdor was cross-endorsed by the Conservative and Independence parties, and he will appear on the ballot on those lines next week.

Freier is not worried.

"I was told for the past 100-plus years, it had always been a Democratic candidate that has won this seat. So basically for more than a century if you win the Democratic primary you basically won the election," she said.

That trend will continue. Avigdor told WNYC his presence on the ballot is a holdover from the cross-endorsements in the primary, and he wishes Freier the best. It’s competition in name only.

That’s true for most of New York City. The real battle happens behind the scenes, before the primaries, when political power brokers pick the judicial candidates. In the general election, voters often see just one name.

There are two main ways to create more contested judicial races. State legislators could reform the laws on judicial elections. Or, New Yorkers could overhaul the state constitution.

In 2017, a ballot measure will be put to New York voters, about whether or not to hold a constitutional convention. It's a chance to enact changes that can’t typically get through the legislature.

"All too often public opinion is not reflected in the legislative action in Albany," Governor Andrew Cuomo said in January's State of the State address. "A constitutional convention that is properly held — with independent, non-elected official delegates — could make real change and re-engage the public."

Everything would be on the table. The convention could reform election law, restructure the courts and streamline arcane legal codes. And, it could also open the door for things like fracking, pension reform and changes to state education spending. Groups from all sides of the political spectrum would wade into the fray.

That's if voters choose to hold a convention. But Barbara Bartoletti of the League of Women Voters of New York said the structure of the convention can turn off the electorate.

The last time New York had a constitutional convention was 50 years ago. Most of the delegates were members of the legislature or judges, Bartoletti said.

"As it is set up currently, it would be literally an insider’s game," she said.

The system could be opened up, making it easier for regular people to become delegates. But that, too, requires action from Albany.

"That’s the catch-22," Bartoletti said.

For most New Yorkers, the convention isn’t on the radar yet. But voters can expect to hear a lot more about it, as soon as the presidential — and judicial — races are over.