I'll admit, I was late coming to Kim Gordon. Sonic Youth, the noise-punk band she started with her husband, guitarist Thurston Moore, wasn’t the soundtrack to my youth. And Gordon didn’t directly influence my personal development in the same way that Bikini Kill’s Kathleen Hanna or Madonna have. I can’t even remember the first time I heard Sonic Youth, and yet, somehow the band's music slowly -- almost secretly -- crept into my life. Eventually, I became an intensely loyal fan.

So, when Gordon and Moore separated in 2011, and the band soon crumbled along with them, I, like many, grappled with the fracture. Together, these were people that I had grown to respect so much: they enjoyed art, they travelled the world, they were “cool.” And, perhaps most importantly to my sentimental self, their artistic and marital relationship seemed so stable from the outside. After the split, I observed each of them carefully, like a sad kid tracking errant and unpredictable adults. Intentionally or not, I suppose I was choosing sides, or at least trying to understand exactly what had happened.

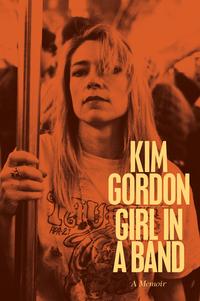

Now, in her new memoir, Girl In A Band, Gordon tells her side of the story, plus much much more about her life and career in music. And she wastes no time filling in the gaps in often uncomfortably transparent detail. The book starts right at Sonic Youth's end -- its last-ever tour in 2011 -- a moment that also marked the end of her marriage. Within ten pages, I was sucked in, and on the verge of tears on my frigid morning commute as I read the words “I don’t think I had ever felt so alone in my whole life.” The way she so freely offers up intimate thoughts and finds no shame in exposing her broken heart, all of that typical artifice and rock-star distance quickly strips away.

Girl In A Band isn’t only a melancholy tour of regrets. It's also a thoughtful window into a dynamic artist’s life, from her early experiences in underground music and culture, to her 30 years spent with Sonic Youth, and as an influential woman and feminist in the music industry, to the array of projects she's working on now. And just like the music she creates, sometimes the narrative doesn't play nice. For better or worse, Gordon also includes some pretty cringe-inducing critiques of well-known names, turning the same boldly penetrating reflective gaze back onto to her peers.

But, like Patti Smith’s Just Kids, and Viv Albertine’s Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys -- or Bjork's recently-released "complete heartbreak album," Vulnicura, for that matter -- Girl In A Band takes its place on a small but expanding shelf of music memoirs not only written by women, but established and previously private artists redrawing their public perception, asserting their flawed humanity, in the face of an awful lot of reverence and cumulative mystique.

I recently had an opportunity to talk with Gordon about the process of writing Girl In A Band, and her thoughts on women in music right now. Plus she describes her relationship to fashion and body image, and her current experimental music project Body/Head.

Rachel Neel: What compelled you to write this book?

Kim Gordon: Money? Truthfully, I had to actually find other source of income, and I was terrified about getting a 9 to 5 job. [laughs] I just wanted to clear the air. I like writing and people started asking me if I was interested in doing a memoir because I think that memoirs are the new rock record -- or something. In the end, it’s just a book, it’s a story. I tried to make it a story about my whole life; the break-up is certainly part of the story and it helps create this arc and it lands me where I am. I just never really thought of myself as being that interesting. As you see there are no sex, drugs, rock 'n' roll in the book.

RN: The book which is emotionally open and I was wondering what inspired that? Were there other writers that inspired your approach?

KG: Well, I like Joan Didion a lot --- her essays. I wasn’t really reading any memoirs while I was writing it. I didn’t want to be influenced and, I’d never really done anything as conventional as this. So I was worried about that. Actually, I was reading that book Flamethrowers, Rachel Kushner's book, and I liked the the sense of space it had and she talked about her character first coming to New York and feeling like an outsider. I definitely related to that.

RN: Where did the title Girl In A Band come from? And specifically, why use the word "girl?"

KG: It was something that was thrown out as a working title. I didn’t come up with it. I thought that I would come up with something better, but I just didn’t. Everything else was too heavy or had too much other meaning. I like the irony of it, and it’s what all female musicians hate being asked. It’s like "What’s it like being a woman in radio?" And it’s a legitimate interest -- but I just feel like always there is another question, like "What is it like being a man in rock 'n’ roll?" or "What is it like being a performer in rock 'n’ roll?"

RN: You played in Sonic Youth for close to 30 years, and continue to make music now with Body/Head. What is it about music that’s kept you enthralled throughout the years -- as opposed to painting and writing? What do you like about the band dynamic?

KG: Bands are kind of like machines. They start up and they keep going until they break up. But you can’t just collaborate with anyone, and I think that’s what makes bands so special. There is a certain chemistry or dynamic that works -- kind of a dysfunctional family. You know you do things for certain reasons, but you don’t really know why you do it this way as opposed to that way.

RN: Throughout the book, I felt like I was learning about people that I’ve watched and people in the industry, and it’s not always positive. What was your feeling about publishing negative critique about people?

KG: I wasn’t trying to write negative critique about people. [laughs] I was just actually just trying to tell the truth, which am I not supposed to do that? I mean, I thought I actually handled them with kid gloves. I was trying to explain certain sociological conditions that were going on at the time in indie rock or just kind of give a little meaningful context to all the just meaningless information that flies around on the Internet and other media. When you write a memoir, it actually makes you have to really face yourself. And just instead of everything being kind of blurry, it makes [you say] "Okay, this is my life – this happened, I met this person. All of these people are in my life." The other thing about writing the book is that I knew almost nothing about my mother, like her inner thoughts. So for better or for worse, Coco, my daughter, will know a lot about me. [laughs]

RN: I really loved those moments in the book when you write about Jane Birkin and Francoise Hardy. Now that you are that woman, now that you’re the Francoise Hardy, you’re just grown and you’re somebody I look at… Who do you look to? Who are your fashion icons at this point?

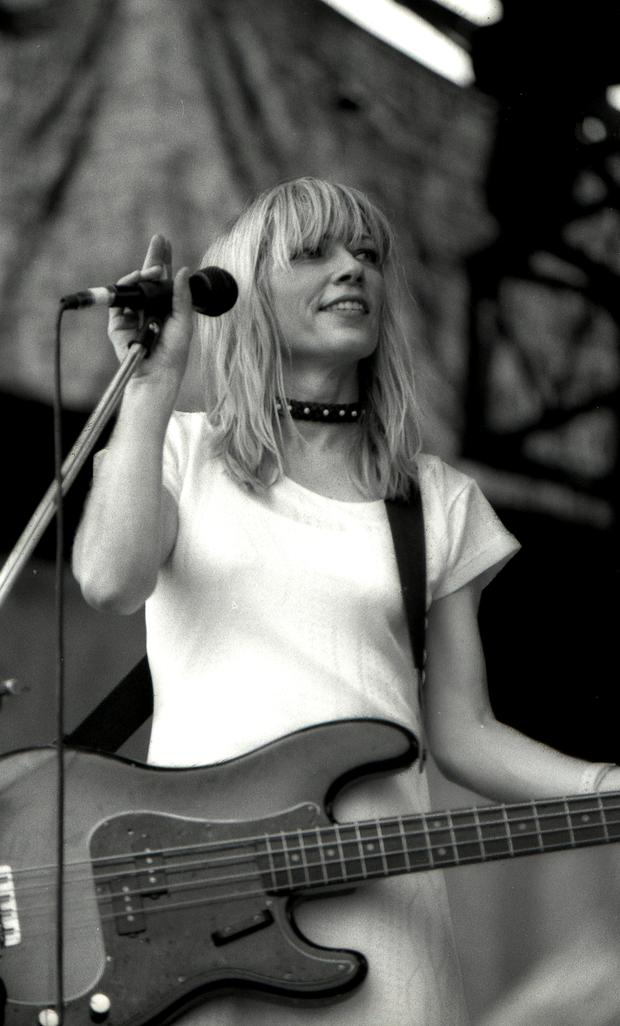

KG: Not that I try to dress like them or anything, but I think true fashion icons are Chloë Sevigny or Lizzi Bougatsos from Gang Gang Dance. My daughter: I like the way she dresses. I just feel like it becomes harder to feel your own identity and not look ridiculous. You know, unless you're Parisian; I think that older Parisian women can get away with wearing like orange patent leather Chanel sneakers I would feel like a crazy woman. I got into contrasting -- "what’s not rock?" -- the opposite of what you're supposed to dress like if you’re rock 'n' roll. But, I’ve got my St. Laurent leather pants, too, which more and more I rely on because it’s easy. But I feel like I’ve never been that intentional and my idea of fashion evolved in such a like spazzy janky way.

RN: When did you start to feel comfortable with how you dress?

KG: I don’t. I really still don’t feel comfortable. I mean when I look back and I go "Okay, the oversized t-shirt with the choker and the boots really worked," But at the time I wasn’t so sure. [laughs] I would wear a choker, but, I don’t like my neck now – my aged neck. [laughs]

RN: You talk very honestly throughout the book about your own motivation. At one point you say, ”Be inside of that male dynamic… looking out…” Has that perspective shifted for you at all? Have you dismantled that feeling of "outsiderness?"

KG: Yeah, for sure. [laughs] I’m done with that.

RN: Does that question not exist for you?

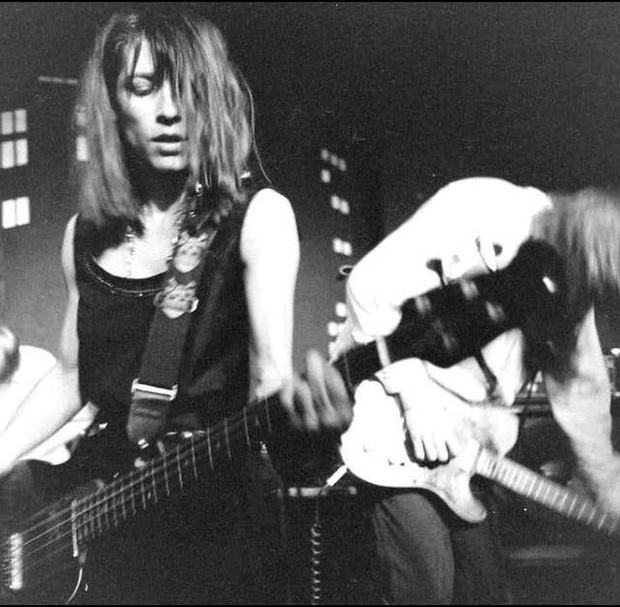

KG: No, I mean, I think that maybe it’s the older brother syndrome or wanting to find a better brotherly relationship with someone. I like electricity; it's exciting performing. That’s what I’ve taken away from that experience: people like electricity. It’s exciting and it’s sexy and it's the movement of playing with an electric guitar. And I’ve explored that a little with art performances and dancers and that’s what I’ve taken away from that.

RN: Do you think that the music industry’s relationship to women has evolved at all, changed?

KG: Well, I think that there are more women playing music on all levels. Mostly, the interesting thing to me is that there are more women playing experimental music -- rock, trip-hop, noise… whatever. So, you know I don’t think that’s a question anymore. It’s more that people are interested in the fluidity of gender. [Some] women in the mainstream... use sexuality more interestingly than others, but there are different ways to also be sexy. You know, I don't think, I think that pornography is more infiltrated in the world now, so people are desensitized to actually sex as a selling point or something.

RN: You’ve always worked with both music and visual art. Do you identify with one or the other, or does each satisfy a different creative itch?

KG: I’ve always seen myself as a visual artist, basically. That’s pretty much how I identify. Which is why I feel that the experimental duo with Bill Nace (Body/Head) feels comfortable to me. It’s less conventional than Sonic Youth was. Sonic Youth became more conventional (with) better songwriting, but I also felt.. I became a better singer or was better at finding songs that fit my style better. But I felt always a little bit like I should be doing something else.

At some point I was like, "Time’s going by. I need to get back to back to what’s most important and how I locate where I am in the world." And that’s not to say that I’m not super proud of Sonic Youth and everything I was part of and grateful.

I had no intention of playing music at all. I was really more making art -- it’s just that Bill and I came up with this name and I thought, "Man that’s really good, we should really make a band." How did you come up with that name Body/Head? You know, we thought, I just really thought I’m gonna make music, you know there’s really no money to be made in the music world – I’m gonna make music that I don’t have to promote. I can just play it – I don’t’ have to worry anything about it. It can just be purely fun and free and that’s how we started playing.

RN: Do you keep up with new music? What are you listening to lately?

KG: I've been traveling a lot, so I just listen to stuff on my computer: Nas, WuTang, Kurt Vile, Fleetwood Mac. Don't [look] to me for musical inspiration right now. I don't know, I don't really hear that much new music that I like. I'm kind of rediscovering older music and occasionally I'll hear older stuff that I like that someone will turn me on to. I'm new to Fleetwood Mac in last four or five years.

RN: Really? What's your favorite record?

KG: Oh, god. Uh, Tusk.