NYPR Archives & Preservation

NYPR Archives & Preservation

The 'King of the Twelve-String Guitar' is a WNYC Regular Through the 1940s

George Harrison once remarked, "No Lead Belly, No Beatles,". This was not hyperbole. Inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame (1986) and the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame (1988), he's influenced generations of musicians and WNYC can proudly claim it gave him a seat in front of our microphone.

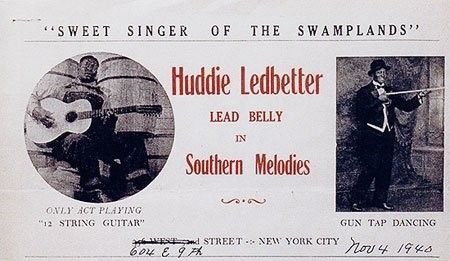

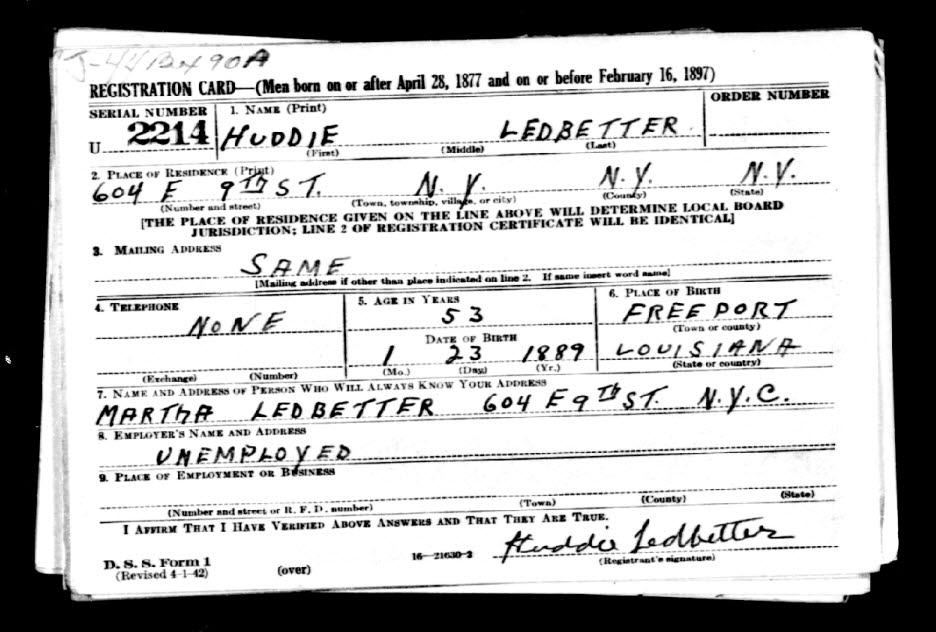

Huddie Ledbetter, better known as 'Leadbelly,' and 'Lead Belly'[1], was a virtuoso of the twelve-string guitar and renowned folksinger and bluesman who had no less than four weekly programs on WNYC between 1940 and 1948. I suspect that none of the shows ran for more than five months at a time because of the demands for gigs outside of the station and ongoing record studio sessions. The folk and blues legend also appeared frequently in the WNYC studios performing for other station programs like Folk Songs for the Seven Million, the annual February WNYC American Music Festival folk, jazz, and swing segments, the Metropolitan Revue with Ralph Berton and later, Art Hodes, as well as Oscar Brand's Folksong Festival.

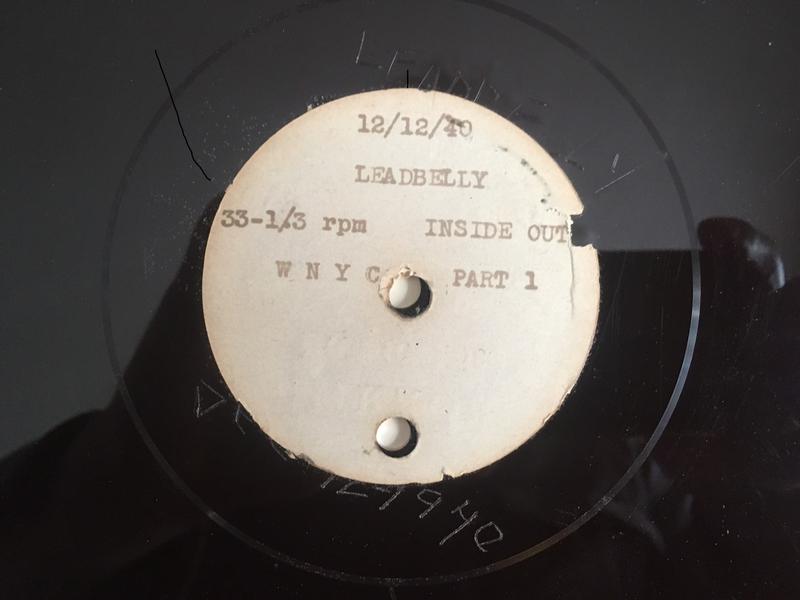

The earliest recording we have of Lead Belly is from the Metropolitan Revue with Ralph Berton, broadcast on November 7, 1940. On the segment, from Moe Asch's off-air recordings of WNYC[2], he performed How Long Blues; Red River Blues, and Wrote Me a Letter Blues.

According to the Masterwork Bulletin, WNYC's program guide, November 7th was also to be the premier of his first show, Folk Songs of America (November 1940-March 1941). In a station oral history interview, Lead Belly's original producer, ethnomusicologist Henrietta Yurchenco, described the program as largely improvised by a consummate performer who was totally sure of himself musically and always positive.

I could set my clock by the time. He always arrived on time. And he was always so immaculately dressed. There he was in this double-breasted gray suit, his white [shirt], this black bow tie, carrying his 12-string guitar. So, we would sit in the studio and in my little office and write out a skeleton script. And, of course, Huddie would just continue. I mean, what he had to say was about his own life and it was colorful and it was magnificent. And after all, he is still considered one of the great blues singers of all time.[3]

Listeners seeking lyrics to the songs were always encouraged to write in and according to Henrietta Yurchenco, Lead Belly would respond on his stationery.

The following shows are listed in the station program guide: November 14 with Woody Guthrie - Railroad Songs; November 21 - Workhouse Songs; November 28 - Wheat and Ax Chopping Songs; and December 5th - River Songs. It's likely Lead Belly and his producer Henrietta Yurchenco did not always stick to the program guide listings so it's difficult to pinpoint the date of the following program of work songs, although I suspect it aired sometime in the fall of 1940.

It features Lead Belly with the Oleander Quartet, consisting of tenors George Boyd and Cecil Murray, baritone Harold Scott, and basso George Hall. "The WNYC show attempted to simulate recordings Lead Belly had made in June 1940 for RCA/Victor, when he was paired with the popular and polished gospel group, the Golden Gate Quartet," according to the Smithsonian's Jeff Place.[4] Performed are Yellow Gal, Cotton Fields, Cotton Needs Pickin Bad, Grey Goose, Pick a Bale of Cotton, and Irene.

In her memoirs, published in 2002, Henrietta Yurchenco wrote:

Once on the air, Leadbelly would ad lib commentaries about his life, his youth on Fanning Street, a red light district, his experiences with cocaine, back breaking field work, his sexual exploits and disappointments, and his years on prison farms. He would recall the time spent as the "eyes" of the great bluesman Blind Lemon Jefferson, leading him through southern streets to play for nickels and dimes. After each broadcast Leadbelly would ask me, "Did you understand everything I said? Folks up north don't understand southern talk and I want them to know what I'm talking about." But he really had no cause to worry; the meaning of his songs was never in question.[5]

The program also came about in no small measure with the assistance of Woody Guthrie, who appeared on many of the shows.

As the Ledbetters had sheltered Guthrie, the Oklahoman returned their loyalty that summer and fall. He worked with Leadbelly to shape a program for WNYC --Guthrie to serve as the unpaid host-announcer. He appeared with Leadbelly at the audition, then repeatedly pressed the station's managers to give the black songster his own show. Only after the programmers relented and the sympathetic Yurchenco became the producer of the Wednesday evening show did Guthrie back away. Guthrie's musical judgment and faith in his friend were validated.[6]

Lead Belly's December 12, 1940 program with Woody Guthrie features ballads. Guthrie sings his classics about Tom Joad, John Hardy, and Jesse James.

The program guide listings continue: December 20 - Teamskinner's Songs; December 26 - Woody Guthrie, Square Dance Songs. The following five programs for Thursday afternoons at 1:30 pm in January 1941 are all listed as "Huddie 'Leadbelly' Ledbetter and Woody Guthrie."

The February 6, 1941 program was listed as Lead Belly and Guthrie but what the legendary record producer Moe Asch recorded off-the-air that day was Lead Belly performing with the Oleander Quartet. Lead Belly opens the show with Chicken Crowing for Midnight and Blues in My Kitchen - Blues in My Dining Room. The Oleander Quartet then joined Lead Belly with I Went Up on the Mountain and Looked at the Rising Sun. The veteran bluesman performs solo, Good Morning Blues. The quartet returns with Lead Belly on Don't You Love Your Daddy No More. The show closes with Lead Belly performing TB Blues and theme, Goodnight Irene.

Another show with The Oleander Quartet from Moe Asch's collection of off-air WNYC recordings is dated 'December 3, 1941.' However, I suspect this program, and a second labeled 'December 31, 1941,' listed in the Lead Belly discography[7] occurred much earlier in 1941 and are mislabeled for two reasons. The first is because producer Henrietta Yurchenco had left the station for Mexico for an extended period by June 1941 even though she is identified with a producer credit for the the show labeled December 31. The second is because there are neither program guide nor newspaper listings for anything resembling the show after March 1941.

In the 'December 3rd' program, announcer Amnon Balber refers to a previous show with the group singing the cotton picking song which they lead with. The rest of the program is a particularly spiritual-oriented show with Meeting in the Building, We Shall Walk Through the Valley in Peace, Look Away in the Heaven, and See the Sign of the Judgement. Lead Belly then preaches a phantasmagorical sermon about finding molasses, honey, butter, biscuits, and pancakes in heaven. He closes the program with Ain't You Glad the Blood Done Signed Your Name.

The program labeled 'December 31, 1941' reflects on both blues and spirituals, where mortals seek relief from pain. Lead Belly opens the show by accompanying his guest singer, the little-known Anne Graham, who delivers a soulful Look Down that Lonesome Road. She follows with her own spiritual, What Kind of Soul Hath Man. From heavens back to earth Lead Belly continues with a blues piece called Shorty George. It's about a weekly train that ran through the prison farm bringing the women to their men folk. He follows this with When You Lay Down to Sleep, Don't Sleep Too Long ('cause you can't never tell what's going on.') Lead Belly concludes with Packin' Trunk Blues, a piece about love.

February 13 is listed as pre-empted due to the American Music Festival. However, Lead Belly performed a day earlier on the same program with jazz, boogie-woogie, and jump blues pianist Sam Price at the festival. He plays The Axe Chopping Song and TB Blues. (audio courtesy of the Municipal Archives WNYC collection). Ralph Berton is the host. February 12, 1941:

Moe Asch's collection contains a half-hour program from February 18, 1941, for the 35th program of the WNYC American Music Festival series America Tells Its Stories. The Oleander Quartet and Anne Graham join Lead Belly for the segment called Folksongs of the Negro. Performed in the first half are: I Woke Up This Morning, I Went Up on the Mountain, Whoa Back Buck, If It Wasn't for Dickey, I Declare This World's a Bad Condition, You Better Be Ready, and Ain't It a Shame.

In the second half of the program, Anne Graham reprises her performance of What Kind of Soul Hath Man. She continues with What You Gonna Do When the World's on Fire, a spiritual she says was given to her in a vision and Rock Me. Lead Belly returns to give us another rendition of his whimsical 'pancake sermon' along with Blood Done Signed Your Name, Gallis (Gallows) Pole, a "sukey jump" party song for children, and Leaving Blues.

The program guide continues with February 20, indicating a pre-emption due to the American Music Festival; and a final program in the WNYC Masterwork Bulletin series is February 27, 1941, with Lead Belly and Guthrie.

However, the newspaper radio listings in The New York Times continued into March for the early Thursday afternoon program following the Missing Persons report and Moe Asch continued to record these WNYC broadcasts.

March 13, 1941: Lead Belly performs solo the following songs: Grey Goose, Boll Weevil, Yellow Gal, Ha Ha This A-Way, and Leaving Blues.

March 20, 1941: Lead Belly and Anne Graham perform: Take This Hammer, Ham and Eggs, Bring Me a Little Water, Sylvie, Stewball, Pick a Bale of Cotton, and There's a Man Going Round Taking Names. Lead Belly closes with his theme song, Goodnight Irene.

I believe the March 27, 1941 program, for which we have no readily identified copy, was the last Folk Songs of America.

World War II

In the Fall of 1942 during World War II Lead Belly was again a guest on Metropolitan Revue, the jazz program now hosted by musician and educator Art Hodes. The show opened with Lead Belly doing his theme song Goodnight Irene from Folksongs of America. He followed it with Don't You Love Your Daddy No More, Christmas is Coming, and Fannin Street (Mr. Tom Hughes Town). Then stepping up to the mic was Gene Hall with a wonderful rendition of Pinetop Smith's Boogie Woogie. He followed that with a portion of his own Gene Hall Blues before the Moe Asch aircheck cuts out.

In 1943 and 1944 the folksinger and bluesman had a close personal relationship with Elaine Lambert Lewis, host of Brooklyn Public Library's WNYC program Folksongs for the Seven Million. Along with being a guest on Lewis' program, she was the person he called for help when his wife Martha became ill and was ignored at Bellevue Hospital. Outraged, Lewis readily came to the balladeer's aid, forcefully asking staffers if they had any idea who this sick woman was. She described Lead Belly as a great musician, and warned, "Do you want it known that this man's wife died of neglect in your care?"[8]

Lead Belly returned to a regular 15-minute Monday evening slot on November 1, 1943, through the end of the year. On December 20th he was joined by Josh White for a program of 'Children's Play Party Songs.' Beginning with the new year, Lead Belly moved to Saturday evenings through the end of February 1944, according to the WNYC program guides. Following this series of shows, he continued recording for Moe Asch and left for Los Angeles to record sessions for Capitol Records by summer.

In this last program, in which the announcer Herb Stone says Lead Belly is headed for Hollywood, (February 26, 1944), he performs, Don't Sleep Too Long, How Come You DO Me Like You Do, Easy Mr. Tom (instrumental), and Four Way Blues. He closes with I'm Going to Buy You a Brand New Ford with verses dedicated to his wife Martha Promise and record producer Moe Asch.

Also on February 14th Lead Belly appeared with his friend and advocate Alan Lomax as part of the WNYC American Music Festival's Songs the People Sing segment. The first half of the program has survived. Lead Belly opens with Three-way Blues. Lomax sings a traditional tune about the dog Ol' Blue. He then gets contemporary with a Woody Guthrie song that Lead Belly joins in with, Sally Don't You Grieve After Me. Together they sing about a racehorse called Stewball, a famous 18th-century racehorse. (Audio courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives WNYC Collection).

POSTWAR

Lead Belly would again be in the line-up at the American Music Festival on February 18, 1946 with Mule Driving Blues, a medley of gospel verses, Three Day Furlough Blues, Where Did You Sleep Last Night, and Hollywood and Vine. (Courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives - note the original lacquer disc was in pretty rough shape.)

On June 4, 1946, WNYC broadcast a Carnegie Hall "pop" concert that included a performance by the American Folk Music Group for the event's American Folk Music Session, the third part of the show. The Carnegie program listed Mary Lou Williams on piano, with vocalists Lead Belly, Susan Reed, Tom Scott, and the Golden Gate Quartet. Unfortunately, there is no known copy of the event.

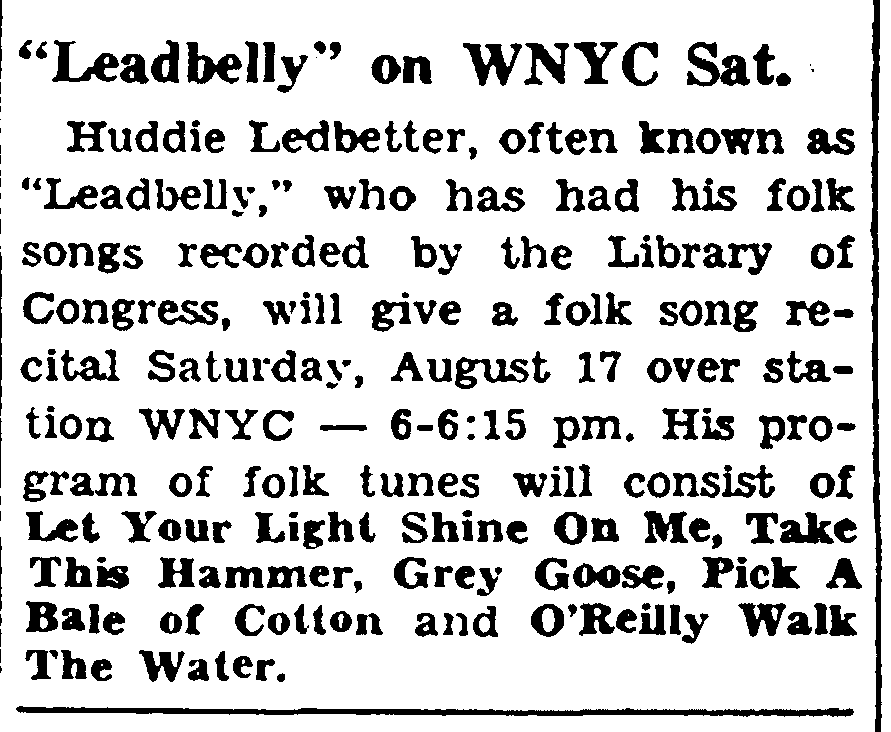

Later that year Lead Belly had yet another limited weekly series at WNYC. Newspaper radio listings indicate this one was on Saturday evenings at 6:00 pm and was called Folk Songs of the Nation for August 1946. Unfortunately, it appears there are no extant recordings. He is also on the roster of performers for WNYC 8th Annual American Music Festival in February 1947 as noted in the station's annual report.

Lead Belly's last regular program on WNYC was on Sunday evenings from August through October 1948. It was called The Story of Folklore. Here are the first and third programs. (Audio courtesy of Cary Ginell and the Origin Jazz Library).

August 1, 1948

August 15, 1948

and October 2, 1948 (Audio courtesy of the Smithsonian's Moe Asch Collection).

Lead Belly's last performance over WNYC appears to be the American Jazz Concert at the 10th annual American Music Festival on February 19, 1949. He is introduced by WNYC's Bernard Buck and jazz author and educator Rudi Blesh. He performed Good Morning Blues, Ain't Gonna Let You Worry My Life No More, and Pretty Papa (Audio courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives).

On this program, it was noted that Lead Belly was planning a series of concerts in France. He spent most of May in Paris doing just that. It was there that he began to have trouble walking and was diagnosed with Lou Gehrig's disease. Upon his return to the States, there were a handful of engagements but by July the disease was getting worse and landed him in Bellevue Hospital. Lead Belly died at the facility on December 6, 1949.[9]

I've attempted to account for the extant Lead Belly appearances on our air. No doubt, there may be some revision as more information comes to light in the coming years.

As mentioned, the Lead Belly influence and legacy are, without question, massive. Many genres of contemporary music have strong links back to this man and we owe him a debt that will never be covered. We can be grateful, however, that WNYC was able to play a significant role in getting his artistry, voice, and name out into the airwaves of New York throughout the 1940s.

_________________________________________________

[1] I have opted to use 'Lead Belly' since this was what he used on his stationary, it is on his tombstone, is reportedly how he signed his name and is used by the Lead Belly Foundation. It should be noted, however, that the primary Library of Congress name authority list has him as Leadbelly, 1885-1949.

[2] Moe Asch, the founder of Folkways Records, made a significant number off-air recordings from WNYC broadcasts in the 1940s and we are extremely grateful to archivist Jeff Place, with the Smithsonian-Folkways collection, for making them available to us. (Frederic Ramsey audio recordings, Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections, Smithsonian Institution.)

[3] Yurchenco, Henrietta, WNYC oral history interview from April 27, 2001. Unpublished.

Henrietta Yurchenco spoke at length with Leonard Lopate on January 17, 2000, about Lead Belly and Woody Guthrie at WNYC 1940-1941.

[4] Place, Jeff, Lead Belly: The Smithsonian Folkways Collection, Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, 2015, pg. 97.

[5] Yurchenco, Henrietta, Around the World in 80 Years, A Memoir, MRI Press, Port Richmond, California, 2002, pgs. 48-49.

[6] Cray, Ed, Ramb'lin Man: The Life and Times of Woody Guthrie, 2004 W.W. Norton pgs 194-195.

[7] Wolfe, Charles, and Kip Lornell, The Life and Legend of Leadbelly, Da Capo Press, New York, 1999, pg. 305.

[8] O'Beirne-Ranelagh, Bawn, (daughter of Elaine Lambert Lewis) email correspondence April 2020. Martha Promise survived Lead Belly by 19 years.

[9] Ibid., Wolfe, Charles, pgs. 254-255.