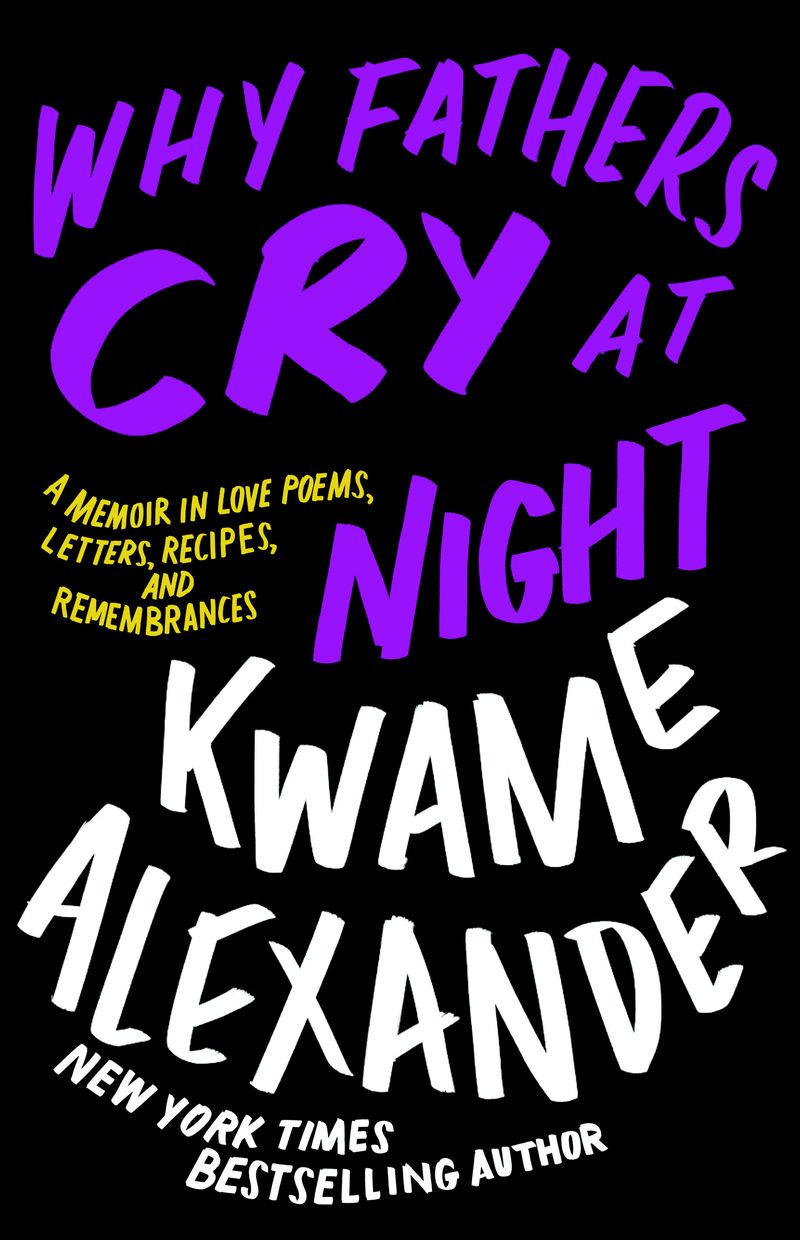

( Courtesy of Hachette Book Group )

Newbery-winning author and poet Kwame Alexander is a beloved children's book author, but now he is sharing more of his life and story with adult readers. Alexander joins us to discuss his new memoir, Why Fathers Cry at Night: A Memoir in Love Poems, Letters, Recipes, and Remembrances, which tells the story of his parents, and his own journey as a father.

EVENT: Alexander will be in conversation with Christine Platt at 92NY tomorrow at 6:30.

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart, live from the WNYC studios in Soho, so happy that you're joining us today. Want to let you know about the show for the rest of the week. On tomorrow's show, we're going to be joined by Dr. Orna Guralnik, the host of the Showtime series Couples Therapy. Then we'll delve into the authors of a new book. We'll talk to the authors of a new book about Steely Dan called Quantum Criminals. Then later in the week, the star of Parade, Tony nominee Ben Platt will be with us. That is all coming up but let's get this hour started with Kwame Alexander.

[music]

You know author and poet Kwame Alexander as the best selling author of The Undefeated an American story, and The Crossover, which has just been made into a TV series. Now Alexander has written a multifaceted memoir. Rather than a linear story, he uses poetry, intimate letters to family members, and recipes, including his mom's famous brown paper bag fried chicken, to invite us into his personal history. Alexander writes about the book, "This is a window into the darkness of doubt and the unbearable lightness of being in love. Remembrances of a poet grappling with loss and longing, questions he's been too afraid to answer. This is putting back together a carrying on, a boy selling his familial cracks, repairing romance, building a monument of love with the only tool he has." His words.

The book is called Why Fathers Cry at Night: A Memoir in Love Poems, Letters, Recipes, and Remembrances. It's out today and on pub day. Kwame Alexander is in our studio. Nice to see you.

Kwame Alexander: Good to see you, Alison.

Alison Stewart: Kwame will also be at the 92nd Street Y tomorrow in conversation with Christine Platt, that's happening at 6:30. What are the outline of this memoir look like? The very, very first stages.

Kwame Alexander: Well, first of all, let me say I can't wait to read that Steely Dan book, because Peg, Deacon Blues, those are the love songs of my childhood. What did the outline look like? There was no outline. This book started as a collection of love poems. I was writing love poems that I hoped would impact readers, and they would enjoy them, laugh, think about their love. As I started writing them, I realized I was telling some sort of story. My editor said, "Kwame, you might want to give some context to some of these poems by including some prose pieces." That led to including some conversations and some letters and recipes. It morphed into what it is now, this memoir, this hybrid memoir. There was no outline. I was just sharing my thoughts on romantic love and familial love and self love.

Alison Stewart: What you describe sounds like a collage.

Kwame Alexander: Exactly.

Alison Stewart: The layers started coming in and then this was dovetailing with this and intersecting with that.

Kwame Alexander: I love the the art metaphor, because I was talking to an interviewer, I feel like I forget who it was, but she said, "Kwame, do you think it was fair for you to write this book and talk about some of your family members?" I said, "This book was a self portrait. This was me talking about me if I were trying--." There are other people in the background of my painting, but if I were to try to do a self portrait of them, that wouldn't have been fair. It's definitely my portrait.

Alison Stewart: Why fathers Cry at Night. Would you read that section of the book and then we'll talk about the title?

Kwame Alexander: I have two daughters, and my oldest daughter when she was 15, she came home one day and she said, "Dad, I want to go out on a date." I was like, "No, you cannot date maybe when you're 30." My wife said, "Kwame, you're really--

Alison Stewart: You're such a dad.

Kwame Alexander: My wife said, "Kwame, you're going to have to deal with this, do the thing you do to get over this, to remember." I wrote a poem to be able to understand what it was like, what my kid was going through. 10 Reasons Why Fathers Cry at Night. One, because 15-year-olds don't like park swings or long walks anymore unless you're in the mall. Two, because holding her hand is forbidden and kisses are lethal. Three, because school was fine, her day was fine, and yes she's fine, so why is she weeping? Four, because you want to help, but you can't read minds.

Five, because she's in love and that's cute until you find his note asking her to prove it. Six, because she didn't prove it. Seven, because next week she's in love again and this time it's real, she says her heart is heavy. Eight, because she yearns to take long walks in the park with him. Nine, because you remember the myriad woes and wonders of spring desire. 10, because with trepidation and thrill, you watch your teenage daughter who suddenly wants to swing all by herself.

Alison Stewart: That's Kwame Alexander from his book Why Fathers Cry at Night: A Memoir in Love Poems, Letters, Recipes, and Remembrances. That poem is also about loss for you.

Kwame Alexander: Yes it's the-

Alison Stewart: It's about love and loss at the same time.

Kwame Alexander: It is. My two daughters, I would walk them to school, hold their hands, swing them around, all the things that parents do. There just came a point where all that stopped. I remember I just moved back from London where I was living for three years, and we moved there when my youngest daughter was in the sixth grade. Every day I would walk her to school and we held hands and by the end of the school year, there was no more holding hands. By the beginning of seventh grade, it was you can't walk on the same side of the street as me. By middle of seventh grade, it was like, "I can do this by myself." I'm like, "I know you can, but I want this." You got to live in the moment as a parent because those moments are so fleeting. They go by so fast. It's about a little bit of loss and trying to figure out how to just be cool with it, I guess.

Alison Stewart: Let's say your daughters pick up this book in 10 years, what do you hope they understand about Dad?

Kwame Alexander: You're asking all the hard questions. I love it. First of all, I'm thinking, "Why are y'all all up in my business?" Then I'm like, but I wrote a memoir.

Alison Stewart: A book.

Kwame Alexander: I've been married twice. I've been divorced and now separated. One of the things I thought about, Alison is when my kids look back on my life, I want them to extend a little bit of grace to me in a way that I didn't do to my parents, and particularly my father, in which I'm now starting to understand to do that. One of the things I want them to know is how I loved and how I love their mothers. I feel like that's important.

Alison Stewart: Very much so.

Kwame Alexander: That the narrative isn't the divorce. It isn't the things that went wrong. It's the things that went right and how we made you. I wrote a piece called How We Made You for my Daughter.

In the future when you're newly married,

and the two of you are half hanging off your bed.

Fingers playing in each other's locks,

your legs braided,

loud garbage trucks beeping outdoors,

no whining children yet to cook for.

And you're talking about leaving your job,

or whose family to visit for Christmas,

or how lucky you are to be loved like this,

or whatever it is you talk about after making love in the early morning.

I want you to know that before our uncoupling,

your mother and I used to work the door at a jazz club in Washington, DC.

And every Thursday night we'd stand at the front door collecting covers,

greeting friends and regulars, feeding each other jerk wings, kissing the hot sauce from our lips,

joking and laughing about this and that,

holding each other when it got chilly.

And later, when we get back to our one room apartment on the other side of the bridge, we'd spread the money out on the bed,

count our haul, smile if we could pay the rent, worry if we couldn't.

And then we'd make our own music.

And without fail, the woman next door would bang on the walls and tell us to turn it down but we wouldn't.

Because we couldn't.

Because we knew how lucky we were to be loved like that.

I just want them to know, how I loved. That's what I want them to know.

Alison Stewart: When did you first start writing poetry?

Kwame Alexander: I was 12, I think, and I had read a lot of poetry and been read a lot of poetry, too, by my mom. As a kid she read to us Lucille Clifton and Nikki Giovanni Spin a Soft Black song and Dr. Seuss. When I was 12, it was Mother's Day and I didn't have any money to buy her a gift so I wrote my mother a poem, because that was the one thing I felt like I knew how to communicate. I thought I was a pretty good poet. I was horrible. The poem was like, Dear mommy I hate Mother's Day, because in my heart every day is Mother's Day and I love you dear Mommy. She cried. I was like, "I'm a pretty good poet." That was the first poem, and that was the beginning of my writerly journey. It didn't start as an idea for a vocation or professional until college.

Alison Stewart: Hearing you read those two pieces specifically. I picked one and you picked one. Is it therapeutic for you writing poetry? I feel like both those poems worked out some stuff.

Kwame Alexander: Absolutely. What did Langston Hughes say? "Poetry is the human heart distilled." It takes these big weighty concerns, themes, things that we're contemplating, pondering, dealing with and it allows us to be able to drill down into a moment that impacts our heart, that makes us feel something. The fastest way to change the way you think or act is by dealing with how you feel about something. That's a basic building block.

Writing this book, I was able to feel and acknowledge and begin to understand a lot of things in my life that were not serving me, perhaps were serving me. Of course as we know when it comes to therapy, you get the understanding of what to do, but then you got to go and do the work, Alison. The book is just the first step. Writing the poem is just the first step. It's acknowledging, but now you got to do the work and that's hard.

Alison Stewart: You tell on yourself in the book about your professor, Nikki Giovanni, and how she when she was your professor, gave you Cs and you did not like that, and you decided you did not like her. You wrote a response play, shall we say, about a certain kind of professor who chain smoked, but then you all later came to be friends. I'm jumping ahead a little bit.

Kwame Alexander: Sure.

Alison Stewart: Do you remember what made you so mad at that moment? Was it ego? Were you concerned that you weren't going to get to do this thing you wanted to do? What was the source of you being so mad at Professor Giovanni?

Kwame Alexander: Again, I thought I was the best poet alive. In my mind I was-- Look, by the time I was 12, I had read Sonia Sanchez, Nikki Giovanni, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen. I had memorized Heritage, What is Africa to Me: Copper Sun or Scarlet Sea, I knew poetry. My father and mother were extremely bookish. I grew up in this house where language and conversation and reading and writing were reward and punishment. I knew words. When Nikki Giovanni came to Virginia Tech in 1987, I was familiar with her because I had read all her stuff as a kid, but more importantly, I felt like I was going to be the quintessential student. I signed up for advanced poetry, had never taken a poetry class, signed up for advanced poetry. I take her class and-

Alison Stewart: That's funny.

Kwame Alexander: -I start getting these Cs, like you say. Yes, it was my ego. I was hurt and I didn't understand it. I thought it was wrong. I thought it was personal. That's that immaturity. I was 18, I went to college at 16. I was 18 years old. It was that immaturity. That's where it stemmed from. Come to find out all these years later, me thinking it was, I didn't like her and she didn't like me. It was just me, it was one-sided. She says to this day, "Kwame, I didn't give you a C." She's in town, by the way. She'll be there tomorrow night. She said, "Kwame, I didn't give you a C, but if I did, you deserved it and you see where it got you." You can't argue with that.

Alison Stewart: My guest Kwame Alexander, the new memoir is called Why Fathers Cry at Night: A Memoir in Love Poems, Letters, Recipes, and Remembrances. Let's talk recipes. When did the recipes come in?

Kwame Alexander: Like I said, I moved to London in 2019. We were there for three years. One of the things I decided to do when we got to London is-- My mom passed away in 2017 and I had felt like I wasn't very close to her. You know how they say when your loved one passes away, you'll hear from them or they'll send you signs, that kind of thing. Especially in our community that spirituality is so important. I grew up in a very spiritual and religious house and a family, and a community. When my mother passed in 2017, I didn't have any connection. I was like, I would pray or meditate or ask, "Where is she? Can I talk to you?" I didn't even know how to do it. I didn't know how to do it.

When I moved to London, I said, "Well, okay, why don't you A, learn how to cook as a way to begin to cook some of the recipes that she made for you as a way to get closer to her?" That's where the cooking thing came in. I taught myself how to cook. One of the first dishes I cooked was her fried chicken because my kid loves fried chicken. That was going to be my thing. I'm going to make this fried chicken for her. The first couple times it was horrible, it was horrible, Alison.

Alison Stewart: Those moms have magic. My mom used to make just a mound. It's funny, she had like the most perfect manicured nail. She was a school teacher. She was-- Everything was in line. Even when she fried chicken, it was delicate, but it was like a mound of fried chicken and it went away quickly as soon as me and my friends got home.

Kwame Alexander: The first couple times I made it, I wanted to make sure it was cooked so it was too burnt or it wasn't cooked enough, which is problematic, or it wasn't seasoned, it was just bland. In London there's no such thing as buttermilk. I remember trying to figure out how am I going to make buttermilk fried chicken. I called my friend Jacqueline Woodson and Jackie said, "Kwame, you should get some milk, a cup of milk, put a teaspoon of lemon in it, squeeze a lemon, teaspoon of lemon, and put it in the fridge. Let it set for 15 minutes, buttermilk." I was like, "Oh, snap."

Alison Stewart: She's like, "Yes."

Kwame Alexander: Yes. My point is, by iteration number 9 or 10, I had figured out how to make fried chicken. I had deconstructed and re-engineered this process because there were no written down recipes. My sisters, maybe they said add some paprika, or somebody said, use this kind of flour. I figured it out. Here's what happened, my kid loved it. We would smile sitting across from each other. I realized, Alison, that I was able to get closer to my mom because I began to mirror the relationship I had with my mom, with my daughter and I'm writing the book at the same time. Of course it just made sense to tell that story and include the recipe. If I'm going to include one recipe, then I'm going to include another one.

Alison Stewart: There's a bunch of good ones. Bunch of good ones.

Kwame Alexander: Thank you.

Alison Stewart: There's a poem in the memoir called an American Love Poem. There's a part that references book banning. The last stanza reads, "I want them to know that banning a book is like banning a hug and that is a dismal storm no child should be left behind in." I'm going to give you the opportunity to sound off on banned books at the moment.

Kwame Alexander: Yes. I appreciate that. My friends and I, we talk about that a lot, because many of them their books have been "banned", Jerry Craft, Jason Reynolds, of course, Judy Blume. Here is my take on it, and I'll share this quick story. One of my books, The Undefeated that Kadir Nelson Illustrated had been banned in a place called Bryan, Texas.

I flew down to Bryan, Texas because I had seen a tweet that one of the teachers had posted how much she loved my books and she was sad that the books were being banned. I flew down to Bryan, Texas, I called the librarian. I said, "Hey, I'd like to come to your school." She said, "Great." "I want to surprise the teacher." I said, "Great. Have them in the library." I get to the school, 100 students are there, the teacher's there, she's all excited when I walk in, "Oh my gosh, you're Kwame Alexander." "Yes." Assistant superintendents are there, three TV stations are there. The place is packed.

Alison Stewart: Wow.

Kwame Alexander: I go in to read from the book that everybody knows The Crossover, the kids are loving it, I'm reading it. Then when I finish, I pull out The Undefeated. I'm in the library, you can't kick me out. I read The Undefeated.

This is for the unforgettable, the swift and sweet ones who hurdle history and a world of possible,

the ones who survived America by any means necessary, and the ones who didn't.

And the kids are on the edge of their seat and the administrator is on the edge of their seat and they see that this book is about hope and upliftment and triumph over tragedy and Maya Angelou quote, "Though we may face defeat, we must never be defeated." At the end, it's all love. I don't spend a whole lot of time worrying about the folks who have forgotten what a book means, who have forgotten their mother's reading to them and how much it meant to them, who have forgotten that. I don't spend a lot of time thinking about them. I pray for them, I hope for them. I spend more time figuring out how I'm gonna get the books in the kids' hands.

Alison Stewart: And, you show up.

Kwame Alexander: And I show up.

Alison Stewart: Kwame Alexander will be at the 92nd Street Y in conversation with Christine Platt tomorrow night at 6:30 p.m. His new memoir which is out today is Why Fathers Cry at Night: A Memoir in Love Poems, Letters, Recipes, and Remembrances. Thanks for being with us.

Kwame Alexander: Thank you, Alison. This was great.

Alison Stewart: This is all of it.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.