To conclude its three months of research, outreach and storytelling this past summer, the four organizations that pioneered the Harlem Heat Project held a community workshop Oct. 15. Participants in the project, as well as invited experts from the fields of public health, architecture, emergency management and climate change, brainstormed ways to alleviate the risks of extreme heat in cities. Here are their ideas:

- Create “cool spaces” that fit into residents’ daily lives. The city already offers “cooling centers,” air-conditioned places open to the public on extremely hot days. But few people use them because they are out of the way. Two teams proposed air-conditioning spaces that lie directly in the path that residents take every day -- such as the lobbies of public housing buildings. Unlike cooling centers, these cool spaces could be restricted to a building’s residents, rather than being open to the general public; but it would be far more convenient to be able to stop off for a few minutes in these spaces on the way to or from one’s own (non-air-conditioned) apartment, than to walk the two or three blocks just to cool off. The nature and location of the “cool space” would vary based on the building’s architecture: it might not be indoors at all, but instead outdoor grilling areas where tenants could cook without heating up their apartments.

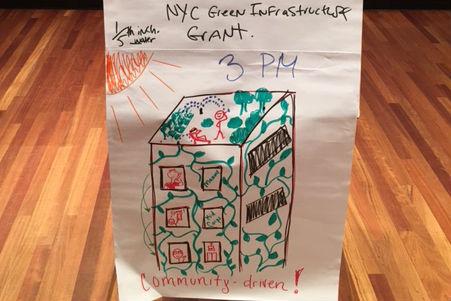

- Plant community roof gardens. This idea would combine the benefits of a green roof (dissipating heat and absorbing storm water) with that of the “cool spaces” above (by providing shade and greenery). Vines or “vertical farms” on each building’s exterior walls would extend the cooling benefits to lower floors. The team behind this concept also saw the roof as a way to catalyze the youth of a particular building: they could come together, learn gardening skills and even grow their own food.

- Personalized heat alerts. In order to conduct its research on indoor heat, the Harlem Heat Project placed small sensors that measure heat and humidity in about 30 apartments. One team proposed expanding this network of sensors to any resident who wanted one, and hooking them up through some sort of wireless network. When the heat in an apartment rose above a certain temperature — each resident would determine what that was based on his or her tolerance to heat — either a central command, or a “telephone tree” of neighbors and relatives would be alerted and advised to check up on the resident. Such a system would allow others to know when an elderly or frail individual was facing risk before he or she ended up at the emergency room.

Each of these ideas present their own challenges. But several individuals at the workshop, as well as partners in the Harlem Heat Project, expressed interest in wanting to pursue a pilot project based on one or more of the proposals. WNYC will follow the Harlem Heat Project into its next phase and keep you informed about it.