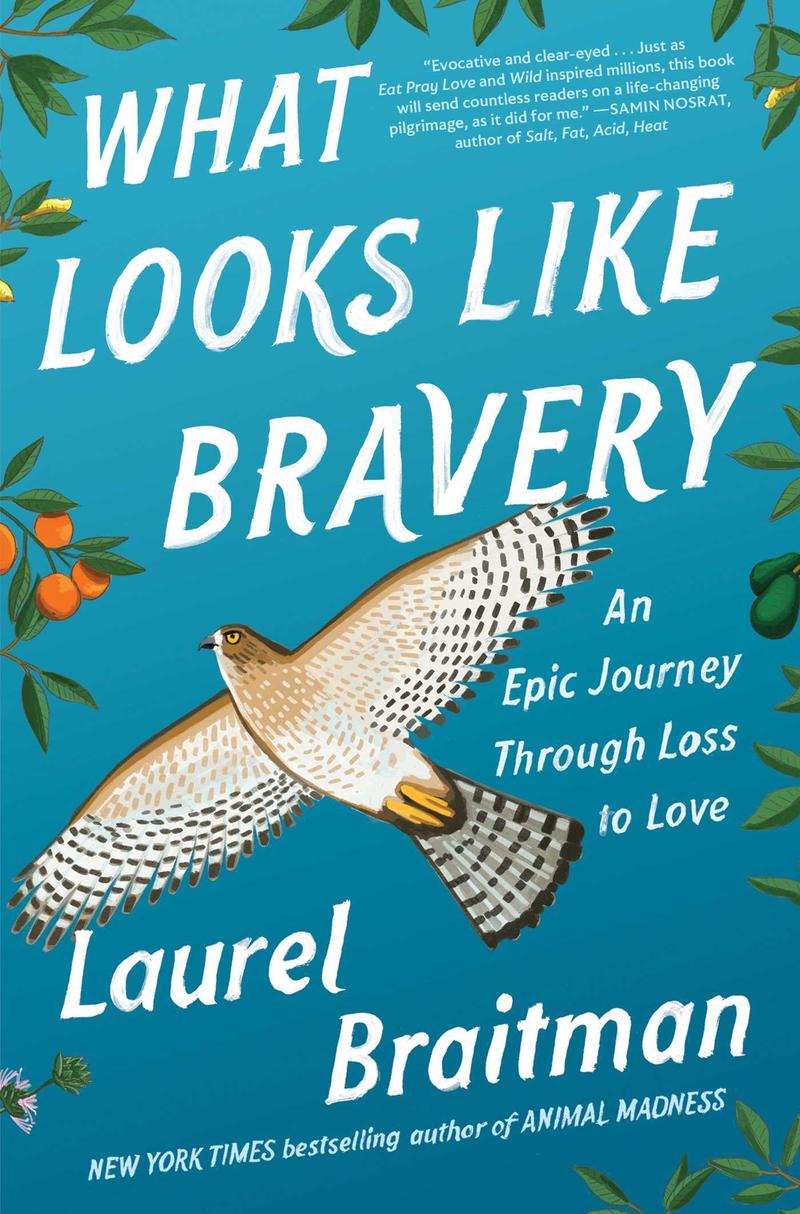

( Courtesy of Simon and Schuster )

After her father died while she was in high school, Laurel Braitman focused on achieving success in school and in work until she couldn't avoid the grief any longer. She joins us to talk about her new memoir, What Looks Like Bravery: An Epic Journey Through Loss to Love and what it means to embrace the pain after losing someone. We also take your calls.

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart live from the WNYC Studios in SoHo. Thank you for sharing part of your day with us. In the first chapter of her memoir, Laurel Braitman writes, "It was 1985. I was seven years old and had one thing on my mind, saving my family." When she was a child. Laurel's father was diagnosed with an aggressive form of bone cancer. Laurel and her younger brother, Jacob, grew up not knowing how much time they had left together as a family.

In her new memoir, we follow Laurel through the process of grieving loss or the loss of what could have been. She lists all the things she would miss out with her dad growing up on a small ranch in her hometown of California, in a smoke-- Let me try this again. Grew up in a small ranch home in a California town. Thank you, Laurel, for not laughing. Deciding on which college to go to, dating, sex, and dodging grief through aiming for success. That is until she couldn't avoid it anymore.

The memoir's titled What Looks Like Bravery: An Epic Journey Through Loss to Love. Laurel Braitman is the author of The New York Times Bestseller Animal Madness and is the director of writing and storytelling at the Stanford School of Medicine's Medical Humanities and the Arts program where she helps clinical students, staff, and physicians communicate effectively. Laurel, so nice to see you.

Laurel Braitman: Thank you so much for having me.

Alison Stewart: Listeners, we would love for you to be part of this conversation. If you've lost a parent or someone close to you recently, we'd like to know how you got through it. Are you someone who tried to keep yourself occupied through grief? How did you get through grief? What advice would you give to someone going through it now? Please share your experience if you feel comfortable. 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC, or you can reach out to us on social media @allofitwnyc as Twitter. If you feel more comfortable sending us a DM on Instagram, you can do that. That is also @allofitwnyc. Why did you decide to write this memoir?

Laurel Braitman: Oh, God. I really didn't want to write it. I wanted to write a true crime novel about a wolf.

[laughter]

Laurel Braitman: I feel like the stories we write sometimes just come for us. I kept sitting down to write other things and I kept writing about this instead. I thought, "Well, I don't even know if I'm brave enough to really do this or publish this, but I think I have to try."

Alison Stewart: When you were writing, were you conscious of trying to work through something or did that just happen as a result of the writing?

Laurel Braitman: Yes, I think I would never say that writing is therapy because if you're a writer, most writers I know are some of the least-adjusted people.

[laughter]

Laurel Braitman: We're not more emotionally involved than the rest of the population. I would say, to write about yourself well and people well, you do have to have empathy for yourself and others. You really can't write about yourself as a character unless you've given your character the benefit of the doubt. It forced me to be nicer to myself than I think I would've been otherwise.

Alison Stewart: How did you write? Did you sequester yourself? Did you write a little bit every day? Did it come in emotional moments and decide to stop and write?

Laurel Braitman: Oh, my God, thanks for asking me this. This is my favorite part of your interviews, hearing about process. I'm kind of a binge-writer and I'm a professor. I teach. I run a commercial ranch with my family, so I have a lot of competing interests. I tend to only be able to write and just do that. I'll take a few weeks when I can, or a month, and I'll wear the same thing. I'll eat the same thing. I won't answer the mail and then maybe I'll do that again three months later. I'm not a good, disciplined, 500-words-a-day kind of a writer.

Alison Stewart: Do you write at home or do you have to go someplace? Some people go get an Airbnb and then sequester themselves.

Laurel Braitman: Yes, I wrote this over the last seven years. I couldn't afford an Airbnb for most of that time. I had to write wherever, but I have been lucky to have some residencies. It is always better to write away from home or even in a hotel room. It's like a blank slate. I also don't like to write anywhere too beautiful because it shames me because what I'm writing on the page can't compare to the view of the window. Sometimes I will actually turn away from a nice view so that I don't feel chastised by it.

Alison Stewart: When you started to write, did you think about it as, "I'm going to look back on my life as an observer of my past self," or did you want to share memories? I'm curious how it started.

Laurel Braitman: It started with a modern love column. I wanted to write about my parents' love language, which was grouchy pets.

[laughter]

Laurel Braitman: I wrote that and then I was like, "Oh, there's actually way more here than I can fit into a little essay." I'm still yet to publish that essay, but I wrote this book instead. I'd say it was the insights first. I really did write a book that I wish I'd had at 21 or 31 or even 41 frankly. I think I wrote the story knowing where I needed to go, which was there was some hard lessons that I'd learned that I wish I had come across a little earlier.

Alison Stewart: You mentioned your parents who are really independent thinkers. This idea that dad's this surgeon, but he's going to be at a farm and they're going to ranch avocados, not farms. As an adult looking back, what was behind their sense, their free-spiritedness?

Laurel Braitman: I have no idea how they came from that. They came from tight-knit Jewish communities in LA and Baltimore. No one in their family farmed or had for generations. I do not know. I think they felt a little hemmed in by where they came from. That's nostalgia for a West that never was like, I think, infected them in some way where they were like, "If we get land, if we get out from under the thumb of where we grew up, we will be freer," and they could rebuild a kind of life they wanted in just their own vision.

Alison Stewart: What impact did that have on you in your development as a human?

Laurel Braitman: Oh, I'm just as weird as they were if not more so.

Alison Stewart: That's great.

[laughter]

Laurel Braitman: I have such a very particular deep entitlement, which is that idea that you can reinvent yourself because I saw that over and over with my parents. Despite hard stuff in their way, they responded by building a life they wanted. I really grew up thinking that was possible even when it looked like it wasn't.

Alison Stewart: Can you describe your dad for us? What was important to him? What was his laugh like?

Laurel Braitman: Oh yes, he was very larger than life. He was a cardiothoracic surgeon or heart surgeon. At heart though, he was a rancher. That was what made him happiest, was outside digging holes, spreading fertilizer, giving my brother and I a hard time. He also was someone who wanted to be able to do everything from wood carving to welding to fixing the irrigation himself to becoming a beekeeper. He just thrived learning new skills. He expected that of us for better or worse, I would say. He was very controlling sometimes in a wonderful way and sometimes in a way that made you wonder who you really were.

Alison Stewart: That sounds like he just had a big brain. Big brains just need to do things. Something to do and think about.

Laurel Braitman: Yes, include pushing their daughters really too hard. [laughs]

Alison Stewart: What's your first memory of your dad being sick?

Laurel Braitman: Good question. He was diagnosed with osteosarcoma when I was three, which is an aggressive bone cancer. He went to the Mayo Clinic and he had his leg amputated. I remember as a kid playing like sliding down his legs as a slide and then I remember the first time I couldn't do that anymore. I remember him coming back with one leg and they came back with shoes for me that they'd bought as a present.

I remember I was just mortified by this still, but I remember throwing a fit and being like, "Shoes are not a present," [chuckles] as with most childhood memories, right? All of the stuff is wrapped up together. The shame of that, and also I did know on some level that it was weird. My dad had one leg, but he would give me his wooden legs to take to school for show and tell. He had quite a sense of humor about it. Frankly, I thought that was normal, that everyone's dad had one leg.

Alison Stewart: We've got a tweet from someone who says his name's Will and he says, "I lost my son almost five years ago. He was nine. I was a stay-at-home dad. He was everything. I wrote to spill my love and save my memories. I shared, but I was ashamed by the approbation. It stopped me writing. Wanted to know your experiences with shame if you had it when you were writing." Not that you should. He wants to make sure you know that but was curious about if you had any feelings of shame when you were writing.

Laurel Braitman: Oh, God, yes. Will, my heart is with you in literally every way. The book is really a journey and a story of what I did with my shame because I had so much shame of how I acted, not just in the loss of my father but in the loss of my home and the eventual loss of my mom and so many other losses. I became, also a story in the book, a facilitator to help grieving kids who lost siblings or who were ill or really kid grief in all of its forms. What I learned from them was that shame is really just another way to control the uncontrollable. We blame ourselves when there's no one else to blame because it's better to blame yourself than it is to admit that you can lose your son for no reason at all.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Laurel Braitman. The name of the book is What Looks Like Bravery. I also want to mention that Laurel will be at P&T Knitwear on Friday, April 7th, so you can get more of this conversation. The book is What Looks Like Bravery: An Epic Journey Through Loss to Love. Let's talk to Alice from the East Village. Hi, Alice.

Alice: I left my mother in my early 40s. It was very hard and I fell apart, but I think I was in so much shame that I didn't even realize that I needed even more help than I was getting. I was seeing a therapist, but it really wasn't enough. I'm not sure what I could have done differently, but I guess you really just have to keep asking for help. I think for a lot of people, that's really hard to do. Apparently, it was hard for me also.

Alison Stewart: Alice, thank you so much for calling in and sharing your experience. That idea of asking for help, it's hard.

Laurel Braitman: It's so hard and it's unclear where to go, right? I think that's another thing I learned from the kids, which is sometimes it's not asking for help. It's just doing things with other people who have also been marked by loss. That itself is deeply normalizing and realizing like in this caller's case and in my case that the guilt is normal. The guilt is grief. Guilt, shame, regret. It's really truly a grief response. You shouldn't believe it if that makes sense. You shouldn't believe that you did something wrong just because you feel guilty. You should feel that guilt or shame or regret and realize that this is the feeling of having lost someone I love.

Alison Stewart: There's a point in the book when you've told yourself a story over and over again. You believed a story about the time near the end of your dad's life and then you come to realize, "Oh, my gosh, that's not what actually happened." Do you think you missed it somehow?

Laurel Braitman: Yes, my dad did right to die or medical aid in dying, but many, many decades before it was legal. It's now legal in California, not legal everywhere. Both my parents actually did right to die. I didn't know that the morning my dad was dying that he was going to do it. Our last conversation was a fight and I hung up on him. I regretted that my whole life and really blamed myself. If I was good, I wouldn't have yelled at him. I wouldn't have hung up the phone and just carried that with me and tried with so much overwork and so many other things to prove myself wrong, that I wasn't bad internally, that the outside validation would convince me I was good. That doesn't work. [chuckles]

Alison Stewart: Later on, it's this idea of you were acting like what a teenager should act like, right?

Laurel Braitman: Exactly. That was one thing, right? Well, writing the book was so helpful because I was like, "Oh, I was 17." I was 16 when these conversations were happening. Of course, that was the healthy thing, was to be rebelling. As you said, I found out 25 years later that what I had thought that he had wanted me to be there and say goodbye was wrong. Here I had been angry and shaming myself for decades without ever being brave enough to really ask the question of, "What had he wanted? Was I really late? Was I bad?" The book is a journey to find my own courage to face those kinds of things.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Michael calling in from Harlem. Hi, Michael. Thank you so much for calling in. You're on the air.

Michael: Hey, Alison. Thanks so much for taking my call. Love, love, love your show. Your I Need a Minute got me through COVID. [laughs]

Alison Stewart: Oh, good. I'm glad.

Michael: All those months. [laughs] Briefly, my story. My mother got ill when I was 10 back in 1977 and she passed away when I was 13. She was 38. Fortunately, I feel I was there in the hospital room with the family and holding her hand. It's interesting. I felt it was a blessing. I felt so privileged. I felt so honored to be able to be there. She gave birth to me and I got to be there to send her off into the great unknown.

It was interesting in that moment when she slipped away for whatever reason, I don't know how I knew the weightedness of it, but the first thing I did was I turned around to look at the clock because I wanted to know what time it was. In that moment, I made a lifelong vow to myself. You get one life, you grab it by the collar, man, and you live it. [chuckles] You dream and you go after those dreams.

I likely would not have become a New Yorker. I likely would not have done many of the things in my life if I did not receive, quite frankly, that gift at that moment. I also came to realize years later that-- and this is decades of reflection that, wow, you let go of that parent figure while they're going through this. I tell friends or people who come from similar things that the first 10 years, sure, I had a mom. The last three years, we had a patient.

Alison Stewart: Interesting.

Michael: You get into that role that you have a patient in the family and this whole business that is the illness and then, eventually, the inevitable passing of that person. That dynamic becomes its own relationship. You have to figure out to yourself, "Okay, so what is my relationship to this non-physical entity that is death and that non-physical entity that is illness?"

Alison Stewart: Michael, thank you so much for calling in. Michael gave us a lot to discuss. That idea of a very ill parent, when you were as young as Michael was or when we're young as you were because there was this idea that, "Will Dad be with us?" I don't want to say beat the odds, but he did a lot to make sure that he would be around for a while. What was that like for you to live in that unknown, that accordion?

Laurel Braitman: Accordion is the perfect metaphor. Sometimes we would have three months between recurrences. Once we had four years, sometimes we would just have the time between the scan where we would then have to say goodbye and prepare to lose him and then he didn't die. In the end, we had 14 years, which he did beat the odds. He was given a six-month prognosis initially.

It's been the blessing and the curse of my life. Honestly, it's the best gift because I do have also what the caller mentioned, which is the seize-the-day mindset, which is amazing. I've been able to do and see more than I ever could have possibly imagined. Also, it can lead to a lot of anxiety. Sometimes you just want to watch Bravo TV and eat a snack and not make your life so meaningful.

[laughter]

Laurel Braitman: You don't want to shame yourself like, "Well, I can hear the ticking clock of mortality. Got to make every moment count," right? There's a balance between doing that and infusing meaning into every moment and also living as if the house of your life is on fire all the time.

Alison Stewart: The name of the book is What Looks Like Bravery: An Epic Journey Through Loss to Love. My guest is Laurel Braitman. Laurel will read a little bit from her book after a quick break. We'll take more of your calls. If you've lost a parent or someone close to you recently, how did you get through it? Maybe you want to offer some guidance to someone else who's going through it right now. 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC.

[music]

Alison Stewart: You're listening to All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. My guest this hour is Laurel Braitman. The name of the book is What Looks Like Bravery: An Epic Journey Through Loss to Love. Laurel, I'm going to ask you to read a little bit if you could set up. Page 64 is where we're going to start.

Laurel Braitman: "After stopping all his treatments, Dad felt okay, good even, at least for a while. I finished up my junior year. Jake finished seventh grade, my brother. We went to the cabin for the summer, our last one together. In fact, we all knew, but no one actually said. Mom made lots of blackberry cobblers and we ate them sitting around the table laughing till our sides hurt and mom snorted or watching A River Runs Through It on rented VHS from Bob's Market."

"We fished for bass and canoed up and down the river and had lots of friends come stay. Dad taught me how to nymph, a fly-fishing technique that uses wet flies instead of dry ones, going for trout underwater instead of on the surface. He got me a backpacking fly rod so I could hike out to good fishing spots on my own. In July, I left for a month to work on a trail crew in Montana and came home fit and strong and full of stories about digging pit toilets and the mountain goats who like to chew the salt off my sweaty backpack straps."

"After Jake and I went back to school in September, Dad took Mom up to the cabin again, just the two of them to look at the fall leaves. He surprised her with a chocolate cake and a green Jeep with a bow in it going big for his last gifts to her. He wrote a card that said, 'Just because.' There wasn't any reason to bother finishing the sentence. They knew. After that, Jake had his bar mitzvah at the ranch, a big party where we serve tri-tip grilled by a cowboy from Santa Maria on a big open rig in the driveway."

"Friend after friend came over to Dad to pay their respects. You could feel the goodbyes in the air like a drop in barometric pressure. In November, Mom and Dad celebrated their 25th wedding anniversary and I started my college applications. To say that Dad was focused on seeing me finish them would be an understatement. 'Did you get them in yet?' was a constant refrain with him and it was driving me nuts. I decided to apply to Cornell early decision and hoped for the best."

Alison Stewart: That was Laurel Braitman reading from her book, What Looks Like Bravery. How did you come to the title?

Laurel Braitman: Oh, the title comes from a mix of my own dogged pursuit to outrun my feelings and my therapist when I was falling in love with my now husband. We were dating. Our "will they one day love" story is a big part of the book. I was lamenting how I really didn't want to love him.

[laughter]

Alison Stewart: You're fighting that one. [laughs]

Laurel Braitman: Yes, I hate love. I really do. It's awful and terrible because as soon as you love someone, you have to worry. It's a curse. Anyway, so I was telling my therapist at the time that I really didn't want to love him and she just laughed at me. She said that I was being brave. I was like, "I'm not being brave. I'm terrified." This was just like I'd already paid. I had my hand on the doorknob walking out of the office and she was like, "Laurel, if you're not scared, you can't be brave." That is where the title comes from.

What Looks Like Bravery is a line from the book. What Looks Like Bravery is often us being scared of something else even more. In my case, I, with my parents' help and encouragement, flung myself into life like a cannonball out of a cannon and did all these incredible things. I pursued my dreams really until my mid-30s and realized that overwork is a coping strategy for pain. I was not going to work anymore. I needed to do what scared me the most, which was actually try and figure out how on earth to feel my own negative feelings.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Judy from Morristown, New Jersey. Hi, Judy.

Judy: Hi, thanks for talking to me. I lead groups for daughters who have lost their mothers and for spouses and partners who have lost their loved ones. It is just amazing to see what the value of tears are to each other. People who have lost their mothers, their foundation has cracked. When they hear other people speaking the same language, using the same vocabulary, expressing the same feelings, there is a visible uplift in the room. It's really important. If you find one, go to it.

Alison Stewart: Thank you, Judy, for calling in. Is that what you found in your work with the group that deals with children?

Laurel Braitman: Yes. First of all, thank you so much, Judy. You're doing god's work. As I mentioned before, there's nothing like peer support. Grief can be such a lonely experience. You feel like you've invented it yourself and every grief is unique. That's, like most human experiences, not true. It's such good medicine to be around other people who have been disappointed by life or challenged by life in some of the same ways.

Alison Stewart: Your father left a list of things he wanted you to accomplish, including writing a New York Times bestseller and getting a doctorate. Looking back, why do you think he made that list for you?

Laurel Braitman: I think he was trying to make sure I would be okay after he died. The way he thought that he could help me the most was by pushing me hard to be successful. I think he felt that without a dad, if he knew that my grades were as good as they could be, if I had applied to college, if I knew that I could maybe possibly be a writer someday that I'd be all right without him. It was his reaching back from the afterlife to try and help me.

Alison Stewart: Did it put pressure on you?

Laurel Braitman: Oh, just a bit. [chuckles]

Alison Stewart: Yes?

Laurel Braitman: Yes. This is a story from the book, but his last gift to me I received six months after he died and it was at my high school graduation. My mom handed me a box and I opened it up. It was a ballpoint or a fountain pen with a note to sign my first book someday. I was 16 when he wrote that note. I took that list. I was nothing if not a good girl for a very long time until pretty recently.

[laughter]

Laurel Braitman: I took that list like a to-do list. I really did.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Brian from the Upper Westside. Hi, Brian.

Brian: Hi, thank you so much for taking my call and that story about the pen. Wow, that's beyond touching. Thank you for sharing that. I am in this club and I joined it about two years ago. My dad had a heart attack. I've noticed in this two-year cycle that there's two groups of us. There's the people who were able to prepare. That could be someone who has illness and then there's that group of us where someone was from their lives without even a thought. My dad had a heart attack and I tried to get home. This was during COVID.

To get a train was impossible. I did end up on one and I ended up having to say goodbye over the phone on the train bawling. That's not how I saw it happening. Since then, I thought about life and the grief and how I felt guilty about not being there. I turned it into a celebration. I don't know if this would work for anybody else. For me, the whole week leading up to my dad, my dad loved music, so I listened to all his favorite artists, whether it be Carole King, whether it be Joni Mitchell, Madonna, things along those lines.

I have my apartment filled with music. One thing that I love doing and I send my mom, my brother, and my dad's sister and brother, I send everyone white roses at the top of the week as I found it to be like a piece of heaven on earth. I wanted everybody to have that. Every year, they know that will be there. That's honoring my dad, but also just to feel like there's a little piece of heaven here on earth.

Alison Stewart: Brian, what a lovely thing to share. Thank you so much. Did you find yourself in any rituals at all?

Laurel Braitman: Constantly. I love this so much. That is such a beautiful, beautiful practice. The white roses, I'll never forget it. Here's what I would say is that I think a lot of us are in both clubs. Both my parents died after an illness, but I did actually miss the chance to say goodbye to my dad despite knowing it was coming. Here's what I would say is that we don't say goodbye often at the time of the person's death and that no matter how you lose a person or frankly a place or a relationship, you may have to honor it and create your own ritual when you're ready.

Sometimes that's a year later. Sometimes that's 10 years later. In my case, it was 25 years later that I buried my dad recently. I said the goodbye that I needed to say goodbye recently. I made the ritual that buried him and left me thinking of him in a new way and sending him off into the afterlife recently. I would tell anyone listening to be creative with your goodbye rituals. Certainly, there is a memorial service or there is an ash-spreading, but that might not be the one that works for you.

Alison Stewart: The name of the book is What Looks Like Bravery: An Epic Journey Through Loss to Love by Laurel Braitman. Laurel will be at P&T Knitwear Bookstore, Friday, April 7th at 7:00 PM if you'd like to continue this conversation, which I think a lot of people might want to do. Laurel, thank you for coming to the studio.

Laurel Braitman: Thank you so much. I'll just add. I'm in conversation with the amazing Maria Popova of Brain Pickings and The Marginalian, so come for her too. [laughs] Thank you so much.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.