Yeni Gonzalez-Garcia has spent a month and a half apart from her three young children, separated by the "zero tolerance" policy for people who illegally crossed the U.S. border. On Tuesday, the family is scheduled to be reunited. Although President Donald Trump rescinded the family separation policy and a federal judge has ordered the government to reunite approximately 2,000 children with their parents, many families remain in limbo. The fact that Gonzalez-Garcia soon will see her children is due to the efforts of her attorney and to WNYC listeners who heard about her case through an on-air interview, and raised money to pay her bond.

Here's what we know about Gonzalez-Garcia and her case.

How She Was Detained

Like thousands of migrants, Gonzalez-Garcia, 29, claimed she was fleeing violence in Central America. She told WNYC she came from Quebracho, an agricultural town, and that she left school after sixth grade to work on a farm with her family. She later got married and had three children but her husband left a few years ago. Around that time she grew nervous about gang violence.

She said people were trying to break into her home and that she was afraid the gangs would recruit her oldest child, an 11-year-old boy. There are reports of rival gangs recruiting young children as they feud over territories.

She said she and her children, who also include a 9-year-old girl and a 6-year-old boy, took buses from Guatemala through Mexico to the United States. She said they were apprehended after illegally crossing the border near Yuma, Arizona on May 19. She said she did not ask for asylum at that time.

Despite the "zero tolerance" goal of prosecuting illegal border crossers as criminals, Gonzalez-Garcia was not charged with a criminal offense. Her attorney, Jose Xavier Orochena, said for some reason the prosecutor declined to press charges. Instead, she wound up in the immigration court system. Orochena said his client would file an asylum claim.

Gonzalez-Garcia is very lucky - most of the people caught crossing the border do not have a lawyer. And while very few asylum seekers win their cases, having legal help increases her chances.

Claims of Harsh Treatment in Detention

Gonzalez-Garcia was initially processed in Yuma at a facility immigrants call the "icebox" because it's so uncomfortably cold. She said she was with many other parents and children. She also said nobody was given food the first two days she was there. Children eventually were offered juice.

Speaking in Spanish, she said she saw many children taken from their parents. She claimed a staffer told them, "You'll be deported and your children will stay in the hands of the government."

Two days later she said her own children were taken without warning. "They didn't say anything," she said, referring to the staff. "They just called them and the children came and then they closed the door. And I could see them pass through the window and that was the last time I saw them."

She said the authorities never told her where her children were sent.

Immigrant processing facilities are run by U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Most immigrants usually stay in these places for a few days before being sent to formal detention centers. But Gonzalez-Garcia was transferred from Yuma to another processing center in Tucson for a couple of weeks. On June 6, she was transferred to Eloy.

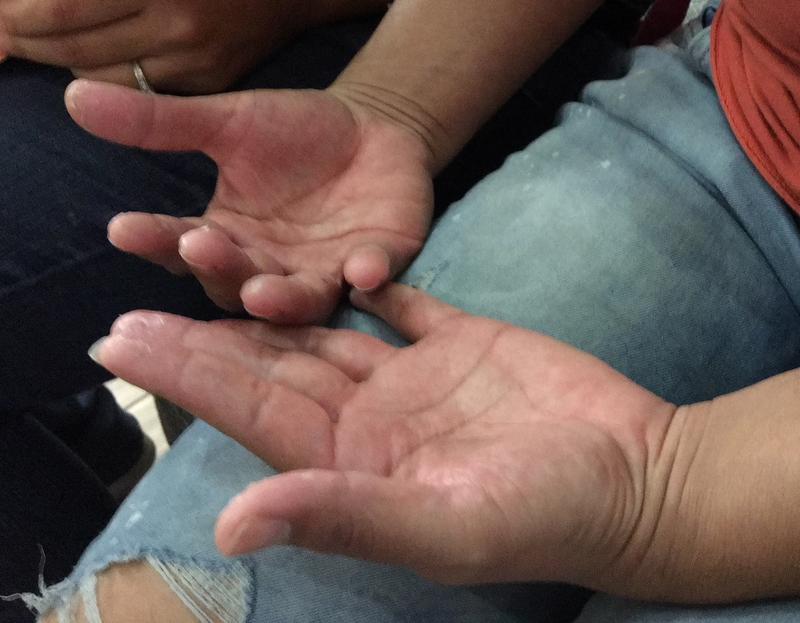

Throughout her ordeal, Gonzalez-Garcia claimed she ate almost nothing but ramen noodles. She also said she did not have a toothbrush, toothpaste or soap for some of the time although it's not clear if she was referring to Eloy or one of the processing centers. She said the water had a lot of chemicals or something in it that caused the skin on her hands to peel.

Response to Her Accusations

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), which is responsible for the Eloy center, said it's "committed to ensuring the health, safety, and welfare of all those in its care. ICE Enforcement Removal Operations officers assigned to the Eloy Detention Center (EDC) in Eloy, Arizona, comply with all aspects of the ICE Detention Standards, to include food service, health and hygiene.”

The Eloy Detention Center is actually run by CoreCivic, a private prison operator that has contracts for a total of eight ICE detention centers. Since 2017, CoreCivic has received $225 million in ICE funding to manage them reports opensecrets.org, which cited USASpending.gov data. Latino USA has reported that there were five suicides at Eloy since 2005, more than at any other detention center.

When asked about the conditions Gonzalez-Garcia described, and whether she could be referring to her time at Eloy, CoreCivic spokeswoman Amanda Gilchrist said: "Our responsibility is to care for each person respectfully and humanely while they receive the legal due process that they are entitled to."

She added that Eloy provides free soap, shampoo, toothbrushes and toothpaste. She said the water is from a well that's inspected by the city of Eloy. And she said the facility serves three meals a day approved by a licensed dietician. She said ramen noodles are never on the menu but can be purchased in the commissary.

Gilchrist also said there's a "robust grievance process" for detainees and that the facility got a 100 percent score from an ICE audit conducted by an independent auditor.

As for Customs and Border Protection, which runs the processing centers, the agency said it "treats all individuals with dignity and respect, and ensures that our operations meet all relevant legal and policy requirements." It also said personnel are supposed to monitor the conditions to ensure that temperatures are kept within "reasonable standards."

The agency did not explain why Gonzalez-Garcia was held in two processing centers for several weeks instead of being moved to a detention center. Her attorney speculated that the detention centers were running out of space in May as more and more people were apprehended at the border.

How She Connected With Her Children

Gonzalez-Garcia claimed she couldn't get any answers about her children until she was allowed to call the children's aunt and uncle in North Carolina. They told her the children were sent to New York.

This is another way Gonzalez-Garcia is among the lucky few: she had family here. She made her children memorize their relatives' phone number. Orochena said the children gave the number to a caseworker who connected with the aunt and uncle. In turn, they found Orochena and hired him to help reunite the children with their mom.

Gonzalez-Garcia said she only had two brief phone calls with her children while she was at Eloy.

What's Next?

Gonzalez-Garcia was driven to New York from Arizona by shifts of volunteers.

Once in New York, she can visit her children at Cayuga, the foster-care agency overseeing the children's care, but they cannot live together until Gonzalez-Garcia passes a background check. The Office of Refugee Resettlement, which is responsible for all unaccompanied minors, has tightened up this process, saying it needs to prevent children from being claimed by the wrong people, traffickers or parents with criminal backgrounds.

The aunt and uncle — who agreed to sponsor the children while their mom was detained — have cleared their background checks. So that means New York is not a final stop for Gonzalez-Garcia and her children. Their lawyer said it's likely they will go to North Carolina, even if they can't live together right away. From there, she will pursue her asylum case.

This story was produced with the assistance of WNYC intern Emily Lang who provided translation help.