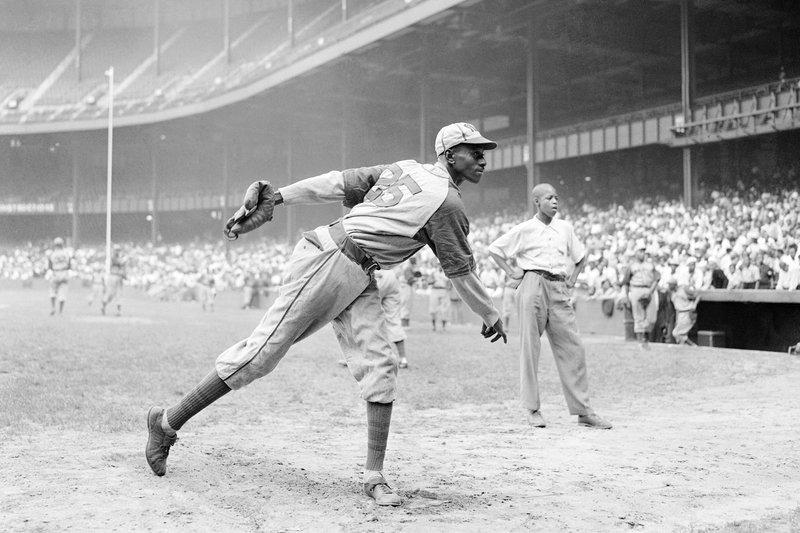

( AP Photo/Matty Zimmerman, File )

In December, Major League Baseball announced that the Negro Leagues would be included in MLB's history and statistics. Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, MO, talks about the effort that went into convincing MLB to take that action and its effect on stats and baseball history.

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC, and now here on February 26th, we'll do our last Black History Month segment for this year on the show. As baseball fans are getting excited that the first spring training games will be on TV this weekend, maybe you heard what Major League Baseball announced in December, that it will recognize the so-called Negro Leagues from when baseball was officially segregated as part of the Major Leagues, meaning all the records of the great players will be incorporated as part of the same statistical database, and much more.

There's also a movement now to rename the Major Leagues annual Most Valuable Player Award for perhaps the greatest Negro Leagues hitter, Josh Gibson, who is sometimes referred to as the Black Babe Ruth. The MVP award is currently named for the baseball commissioner from a hundred years ago, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who kept segregation in the game during his tenure from 1920 to 1944. Here is Josh Gibson’s son, Sean Gibson, speaking in December about renaming the MVP Award for his dad.

Sean Gibson: It's about poetic justice. What I mean by that is, here we had Kenesaw Mountain Landis who denied African-Americans the opportunity to play baseball, how great or ironic would it be to have someone denied replace his name, someone like Josh Gibson? The last thing I will say is that this MVP Award is not just about Josh Gibson. Yes, it will carry Josh Gibson’s name, but this will carry hundreds and thousands of players. There's 3,400 players of records they found from the Negro Leagues. Most of those guys will carry on that legacy to the MVP Award. It's not just about Josh Gibson, it's about all the great players who were denied from 1920 to 1944 the opportunity to play the Majors.

Brian Lehrer: Sean Gibson, the son of Josh Gibson in December. We are very delighted to have as a guest now to talk about some of the history and some of these great American ballplayers by name, including a few women, by the way, who deserve more historical recognition. Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City. Mr. Kendrick, so nice of you to give us some time today. Welcome to WNYC.

Bob Kendrick: Oh, good morning, Brian and thanks so much for having me on the show.

Brian Lehrer: Let's do some big picture history first, and then we're going to invite callers, maybe some people out there who are old enough and lived in the right places to have ever attended a Negro League’s baseball game or maybe even played. We'll invite some caller stories and we'll get into some individual player stories with you, but some big picture history first. I see the Negro Leagues dated as running from 1920 to 1948, but there was Major League Baseball before 1920. What was happening in those earlier decades?

Bob Kendrick: Now, there's been a long history of Black folks playing baseball, Brian. This goes back to certainly right after the Civil War. There were early instances or indications of us playing baseball even during slavery, and so it was not a new phenomena for Black folks to play baseball, it didn't get a organized structure until 1920 here in Kansas City. As a matter of fact, just right around the corner from where the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum operates, the Paseo YMCA. That is where Andrew "Rube" Foster led a contingent of eight independent Black baseball team owners into Kansas City.

They met and on February 13th, 1920, they adjourned having established the Negro National League, the first successful organized Black baseball league. Now, while baseball is recognizing from 1920 to 1948, the Negro Leagues didn't officially end until 1960, so they operated for 40 years in this country.

Brian Lehrer: I was going to ask you about that, the back end of that because Jackie Robinson and the Dodgers integrated the Majors for the first time in 1947, and then other MLB teams took on Black players, but as you say, the Negro Leagues lasted until 1960. I see that some of the people who are your museum honors as having been great Negro League team players played in the 1950s.

Bob Kendrick: Exactly.

Brian Lehrer: Why did the leagues continue after Jackie Robinson, and what caused them to eventually close?

Bob Kendrick: Because it took Major League Baseball, believe it or not, 12 years before every Major League team, Brian, had at least one Black baseball player. The Boston Red Sox were the last team to integrate in 1959 when they signed Elijah Pumpsie Green. They would complete the integration cycle, and by 1960, the Negro League ceased operations because by then the best young Black stars had moved into the Major Leagues or into their minor league system, and so there was no replenishing system.

That Black fan base that had been so loyal to Negro League Baseball, they had left to go see how Jackie and how Larry Doby and eventually Satchel Paige, and Roy Campanella, Ernie Banks, how they were going to fare. There was a natural curiosity to see how they were going to fare because no matter what they had done in building the Negro Leagues and how great and how much talent was in this league, the world still said the highest level in which you could play baseball was in the Major Leagues, so there was this kind of, I guess, aspiration to prove to the world that they could play the game as well as anyone.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, I wonder if there is anyone listening today who ever saw a Negro Leagues game or played at a Negro Leagues game, or ever knew anyone who did either of those things, 646-435-7280. Anyone have a story you're willing to tell or what this historical integration that's been announced by Major League Baseball in December means to you? 646-435-7280. Or if you just have a question for Bob Kendrick, a question about history, a question about an individual player, whatever, for Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, 646-435-7280. 646-435-7280, or tweet your question @BrianLehrer.

Kenesaw Mountain Landis and this MVP Award, Kenesaw Mountain Landis was Commissioner 1920 to 1944. That almost exactly coincides with what we think of as the primary years of the Negro Leagues. Now there's the movement to replace his name and image on the MVP trophies. For those of you who are not baseball fans, this is baseball's highest honor every year, the one player who's deemed the most valuable in the American League, the one in the National League, and maybe they'll replace the image and the name of the segregationist commissioner with the name of perhaps the greatest Negro Leagues player, Josh Gibson. How personally responsible was Landis for baseball segregation?

Bob Kendrick: He certainly carried a lot of weight. Now I know that he was working for the owners, so he wasn't certainly in this by himself, but he was one of the staunchest advocates for keeping the game separate. He had vowed that as long as he was commissioner, there would never be a Black man playing in the Major Leagues. As we tell the story here, Brian, as fate would have it, he died, and then Happy Chandler became the next commissioner. Happy Chandler and Branch Rickey clearly orchestrated his move to bring Jackie Robinson as the chosen one to break baseball's six-decade-long self-imposed color barrier. Of course, Jackie Robinson was handpicked from the great Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro Leagues. Yes, you certainly cannot absolve Landis from his role as being a segregationist as we look at this game.

Brian Lehrer: I read that he even worked to block exhibition games, just nonofficial games that were for show purposes between Black teams and white teams outside the Major League context. Is that true?

Bob Kendrick: Yes, well, we've got a quote in the museum that was said to Rube Foster who formed the Negro Leagues, who was an absolute genius, by the way, Brian, and Landis says to Rube Foster, he says, "Mr. Foster, you give our league a Black eye when your team beats us." What he essentially did was two things; he banned intact Major League teams from playing Negro League teams. For instance, if the Kansas City Monarchs were going to play the St. Louis Cardinals, he wouldn't allow that to happen in uniform, and then ultimately, he banned those very heralded and popular barnstorming All-Star games from being played prior to the World Series because they were outdrawing the World Series.

In this case, folks, we might have the Satchel Paige All-Stars against the Bobby Fella All-Stars or the Dizzy Dean All-Stars, and so you would always have these epic, barnstorming exhibition games that were played with Black teams against teams that were filled with Major League players. These, Brian, they were filling up ballpark from coast to coast, man. Everybody wants to see these games, so they were outdrawing the World Series. Landis didn't like that, but the players wanted to play these games. You know why? Because they were making a boatload of money, so none of these players wanted to stop. He wouldn't sanction them, but he would allow them to play those games after the World Series.

Brian Lehrer: William in East Orange, you're on WNYC with Bob Kendrick from the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City. William, you're on WNYC. Hi.

William: Okay, thank you very much. A quick story. Of course, I wasn't there, but my grandfather who pitched at Columbia University in the late '20s, and for two years, averaged 21 strikeouts the game. He got drafted by the Yankees, hurt his back, but then he played in the semi-pro leagues, and he pitched with Bushwick. He has a story, pitching against Josh Gibson who hit four home runs off him, and my grandfather's apocryphal description was, "The last one hasn't come down yet, it's still going up."

[laughter]

Brian Lehrer: That's wonderful. Thank you, William, that's a great story. Why don't you take the opportunity to tell the uninitiated, Bob, a little bit about Josh Gibson, who, as I said in the intro, sometimes gets referred to as the Black Babe Ruth?

Bob Kendrick: That reference has helped to give people a perspective of how good he was. You will hear that with a lot of Negro League players that people will draw a parallel to a white star because people knew who those white stars were. We are also fond of saying that for those who saw Gibson play, they would call Ruth the white Josh Gibson.

Brian Lehrer: There you go.

Bob Kendrick: Gibson, Brian, was incredible. He is, I believe, the greatest combination of power and average this sport has ever seen. My dear friend, the late great Buck O'Neil would describe Josh Gibson in this manner that he had the eyes of Ted Williams and the power of Babe Ruth rolled into one dynamic package. Folks, his outs were loud out. The third baseman and the shortstop, Brian, were almost in left field when Gibson came up there to play, man, because you could get killed trying to creep in on Johnson. He swung a 40-ounce 41-inch bat. I tell people if you want to try and gain a perspective of the physique of Josh Gibson, think the great Bo Jackson as a catcher, that's Josh Gibson.

Big powerful forms, big, powerful thighs, great eyes. In New York City, he is still believed to be the only man to ever hit a ball completely out of Yankee Stadium. He hit one in the Polo Grounds that they estimated to travel over 600 feet.

Brian Lehrer: Wow.

Bob Kendrick: As I tell people all the time, he wasn't just a great power hitter. Josh was a great hitter, lifetime batting average of 354, and again, in head-to-head competition against Major Leaguers in countless exhibitions, he had over 420 and he was doing it as a catcher.

Brian Lehrer: I saw that he was 6'1", which is big for a catcher. I don't know how he was able to squat down all the way. We actually think of catchers as the squat little guys like Yogi Berra, but we have a celebrity caller in his own right checking in with us on this. The former New York State Governor David Paterson. Hey, Governor, you're on WNYC.

David Paterson: How are you, Brian? I have a story for you about my father who was a very good baseball player and got a tryout with the New York Giants in 1949. He said he was there the whole day, and at no point did they ever let him take the field. There were two Black tryouts and they didn't allow him to take the field. The funny thing is, it's not until today in this interview you're having with Mr. Kendrick that I ever thought I never asked him if he ever tried out for the Negro Leagues.

Brian Lehrer: There you go. Governor, I'm going to leave it there so I can get some other folks on, but that's maybe a telling story, Bob, about Black players even, in that case, two years after Jackie Robinson came to the Majors where maybe the scouts or the team officials were looking the other way so they didn't see the good Black players be good.

Bob Kendrick: Yes, and it vary, Brian, from team to team. Obviously, the Brooklyn Dodgers were far more aggressive than most Major League teams. The Brooklyn Dodgers probably had six Black players before half the Major Leagues had integrated, so Branch Rickey was very aggressive. We even talked about Boston signing Pumpsie Green in 1959. Boston could have had to pick up a litter of great Black talent and just turned their backs on it. I don't know if ownership was getting bad information from scouts, or if the scouts were just basically carrying out the wishes of the Yankee family, but they had chances to sign so many great Black stars as is a lot of teams.

A lot of teams had that opportunity and they passed up so much talent. The National League was far more aggressive, though than the American League. The National League really started winning and dominating the All-Star game, and we saw the pendulum shift even in the World Series because they were bringing so much of this Black talent in. One of the interesting factoids to me, Brian, that really helps people understand the immediate impact that the Negro Leagues had on Major League Baseball, from 1949 until 1959, none of the 11 National League most valuable players were former Negro League stars. It's amazing. That's not even counting rookies of the year.

Brian Lehrer: Does that include Hank Aaron? Did he play at all in the Negro Leagues before he went to the Majors?

Bob Kendrick: He did 1952. I'm so glad you mentioned his name. He's my all-time favorite player. He's my childhood idol as a kid growing up in Georgia. My heart is still a little heavy from his passing, but he played in the Negro Leagues in 1952 with the Indianapolis Clowns. My favorite photograph in the entire exhibition here at the museum is a relatively nondescript photograph of a young Henry Aaron, Brian standing at the train station in Mobile, Alabama. Man, he must have weighed 150 pounds, and he's on his way to go join the Indianapolis Clowns, a skinny, cross-handed, hitting shortstop. Mr. Aaron was a right-hand hitter who was hitting with his left hand on top.

As you know, that is unorthodox. The fear is that you would break your wrist hitting in that manner. Folks, Henry Aaron is knocking the cover off the baseball in a highly unorthodox fashion. When he gets to the Clowns, they put the right hand on top and the rest, as we say, is history. He was shortly after discovered by the Boston Braves, who would become the Milwaukee Braves, who, of course, would become the Atlanta Braves. He will go down in this sport as one of his all-time greatest players, but it all began in the Negro Leagues.

Brian Lehrer: You said he was on the Negro Leagues, Indianapolis Clowns, and we have a caller-

Bob Kendrick: The Indianapolis Clowns.

Brian Lehrer: - it looks like who is a relative of another Indianapolis Clown. Jackie in Jersey City, thank you so much for calling in.

Jackie: Good morning. Yes, my uncle who we had just missed by one year, he passed away last December, his name was [inaudible 00:17:53] Joseph and he-- [crosstalk]

Brian Lehrer: You broke up there for just a second on his name. What was his first name?

Jackie: Hello.

Brian Lehrer: You broke up there for just a second as you were saying his name. What was your uncle's name?

Jackie: His name was Joseph Taylor and his headlining name, he played under the name of Juggling Joe Taylor because he was also credited with being the first Negro at the time, Negro-American man who wrote for the magicians or Jugglers Magazine. In 2015, a young man put a notice out on Google asking had anyone seen or heard of Juggling Joe Taylor. He and his brother run a museum, they stay, somewhere in Ohio. They came to New York and my sister and I took my uncle, we took him and we met them in Harlem and treated them to lunch.

That was one of the very last times that anyone went through the dusty archives and looked up some of the old guys, but Uncle Joe was our rum, our favorite, and icon because we knew when he came around that we were going to be in for a treat with all kinds of things. He was actually an Indianapolis Clown, so I think he told me three seasons he played shortstop. I have pictures and stuff. I have pictures from the '40s and maybe the late '30s and '40s and I can send it, if I got the address of your place, I would gladly try to share them with you.

Brian Lehrer: Do you want those, Bob?

Bob Kendrick: Oh, we would welcome that. Thank you so much.

Brian Lehrer: Jackie you come from a juggler and a Clown in this case. [chuckles]

Bob Kendrick: I tell you what, Brian, the thing about the Clown team, they had a group of guys who were very serious baseball players. If you ask them to dress up in a Clown outfit, you would have to fight them, but they also had these legendary entertainers to the likes of what the caller just mentioned, the likes of the legendary Reece Goose Tatum. Most folks if you've heard that name, you probably heard that name because he was a member of the Harlem Globetrotters and is in the Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield, Mass, but Goose Tatum, folks, was a slick-fielding first baseman for the Indianapolis Clowns.

The things that he could do with that basketball, he was literally a magician with the baseball on the diamond as well and they would put on these shows before, during, and after games. Today we call them mascot, but that's really where the notion came from.

Brian Lehrer: We have just 30 seconds. There's so many more questions I could have asked you. This is so much fun, but I do want to note that you have at least three women who played in the Negro Leagues, who you honor in the Negro Leagues Baseball Hall of Fame. Can you tell us a 20-second soundbite story about one of them?

Bob Kendrick: Toni Stone was the first female of professional baseball. She took the roster place of Henry Aaron. When Henry Aaron signed with the Braves, the very next year, the Clowns signed Toni Stone, and then she was followed by Mamie Peanut Johnson and Connie Morgan, three pioneering women who competed with and against the men in the 1950s in the Negro League.

Brian Lehrer: Major League Baseball in December announced that all the stats, all the history of players from the old Negro Leagues will be considered part of Major League history and Major League stats. We are so happy to have Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City as having been our guest this last part of this hour. This was so much fun and thank you, and so interesting and great for everybody to know who didn't already know some of this history. Thank you so much.

[music]

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.