The Brian Lehrer Show

The Brian Lehrer Show

Monday Morning Politics and Law: Mifepristone, House Judiciary Hearing, Justice Thomas Ethics

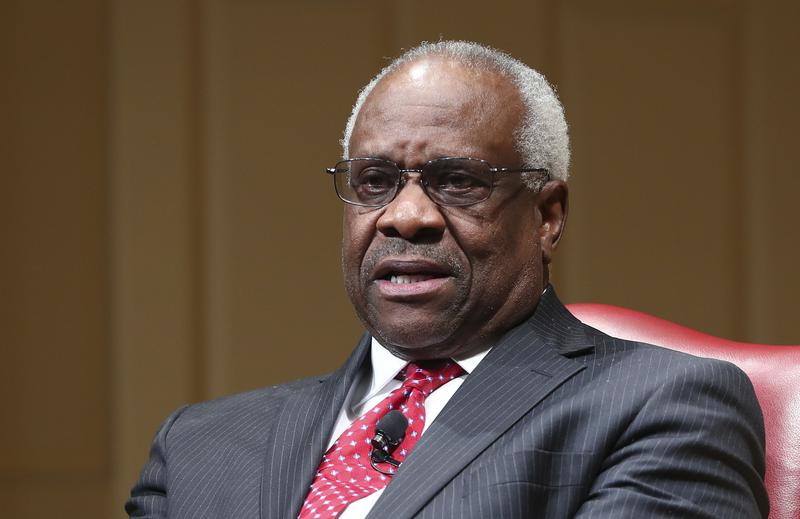

( AP Photo )

Emily Bazelon, staff writer for The New York Times Magazine, co-host of Slate's "Political Gabfest" podcast, Truman Capote fellow for creative writing, and law at Yale Law School, and author of Charged: The New Movement to Transform American Prosecution and End Mass Incarceration (Random House, 2019), talks about the latest national legal news.

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, everyone. We'll start the week as we usually do with some Monday morning politics. A lot of the politics as we begin this week are focused on the courts. Even as we speak, the Republican-led House Judiciary Committee is holding a hearing in Manhattan that it claims is about how DA Alvin Bragg is not doing a good job for crime victims, but seems to really be a way to try to discredit Bragg after a Manhattan grand jury indicted Donald Trump.

Then there is the high stakes court drama over the past 10 days, of course over the abortion pill, Mifepristone, such a rare occurrence to have a federal district court, then an Appeals Court and the Supreme Court weigh in on a case in rapid succession like that. The stakes, of course, are so high for American women. We'll explain where that stands. There are new revelations about Supreme Court Justice, Clarence Thomas, his ties to a major real estate developer, how serious a conflict of interest do we have here?

With us now is Emily Bazelon, staff writer for the New York Times Magazine, co-host of Slate's Political Gabfest podcast, Truman Capote fellow for creative writing and law at Yale Law School, and author of the book Charged: The New Movement to Transform American Prosecution and Mass Incarceration. Emily, always great to have you on. I know you're joining on short notice today. We really, really appreciate it. Welcome back to WNYC.

Emily Bazelon: Happy to be here. Thanks, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: There's so much that's new and changing every day that you're going to do a lot of explaining today. It's like the old I Love Lucy show. Lucy, you're going to have a lot of explaining to do but in a different way. Emily, you're going to have a lot of explaining to do. With so much changing so quickly on the abortion pill, could you start by just explaining Friday's Supreme Court ruling? For one thing, it's not the final word on the case, even though it's the Supreme Court, right?

Emily Bazelon: Yes, it's far from the final word. On Friday what the court said and really this is just Justice Alito because he's the Justice who's in charge of Texas, where this suit originated. It was just him saying status quo stays the way it is until the middle of the week, until Wednesday at midnight. Basically, he's giving both parties a chance to file briefings in front of what's called, what's the emergency docket for the Supreme Court also called the Shadow Docket.

Basically, the Supreme Court is going to, presumably by Wednesday at midnight, issue some ruling that in itself will also be temporary. We're at a very preliminary stage of this case, it's going to determine, at least, in the short-term, the availability of the drug, Mifepristone, across the country. That's one of the two drugs that's used with for abortion pills.

Brian Lehrer: Alito is the one who was the primary author of The Dobbs decision that struck down Roe. Would you have expected something more explicitly anti-Mifepristone coming from him the other day?

Emily Bazelon: Not really, because this is just purely procedural. It's okay, what's supposed to happen in the next few days. The FDA has this order from the Fifth Circuit that it's anticipating which would tell it to change the way in Mifepristone is available across the whole country. In fact, the most important part is that Mifepristone would no longer be able to be mailed, which is a big deal for access.

There's also this conflicting order from a federal judge in Washington State. He was sued by 17 blue states and Washington DC, and he's ordered the FDA not to make any changes in the availability of Mifepristone in all of those states. The Supreme Court is saying, "Okay, wait a second, give us a minute to catch up and figure out what we're going to order going forward."

Brian Lehrer: Is Mifepristone any less available today than it was when this whole saga started a week ago last Friday?

Emily Bazelon: No, it is the same amount of available, it is still being mailed. I'm really glad you asked that because I think for a lot of abortion providers, the confusion around that has been very frustrating. They are still able to mail the drugs, the manufacturer of the drug can still send it out as of now.

Brian Lehrer: There's going to be another Supreme Court ruling on Wednesday, two days from now, is that what you said?

Emily Bazelon: I think so, yes. The Supreme Court, it could extend this order to give itself more time. What we know now is that the FDA and one of the companies that makes Mifepristone, Danco, has filed briefs saying, "Please don't take these drugs off the market." They are arguing based on lots of evidence that they are safe and effective, that there's nothing wrong with the FDA's approval of this drug. Now, the other side, the plaintiffs who sued arguing that the drug is too dangerous and to block the FDA's approval from years ago, the plaintiffs now are filing their briefs by Tuesday and presumably the Supreme Court will issue some order on Wednesday.

Brian Lehrer: That could send it back to the lower courts and it would work its way back up to the Supreme Court?

Emily Bazelon: Yes, we're still in the land of preliminary injunctions. There has not been any real trial for proceeding on the merits about this drug. We're starting out with this quite odd and unusual case in which the plaintiffs formed an organization, an anti-abortion organization in Amarillo, Texas, knowing that there's one federal judge there, Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk, who had a very anti-abortion record. He issued a sweeping ruling, halting the FDA's approval of Mifepristone going all the way back to the year 2000.

Then the Fifth Circuit came in and said, "No, that goes too far, but we are going to prevent the FDA's changes to Mifepristone's approval from continuing." The most important change the FDA has made which was in 2021, during the pandemic was to say that Mifepristone could be mailed without an in-person visit to a clinic. Lots of online providers, telehealth services have sprung up in blue states around the country mailing Mifepristone. That's the biggest thing at stake in this case.

Brian Lehrer: Other than that, the judge in Texas might be anti-abortion and he apparently has an act of anti-abortion background. We can talk about that. Is there any legal basis for saying, well, what they started doing during the pandemic with this telehealth availability without an in-person visit to a doctor is somehow against the law? Why is that question in court as opposed to a policy decision for the FDA?

Emily Bazelon: Right. That's a crucial question. Usually, when a federal agency like the FDA makes a decision, courts defer, to a large degree, to the agency's expertise. Here the FDA is on the record. There were lots of studies before the pandemic, during the pandemic about mail order access. They really strongly show that Mifepristone is safe and effective, whether or not you go to a doctor before you take it. That's what the FDA relied on. I think, normally, courts would defer to that decision-making. We have this unusual set of circumstances and that is not what happened.

Brian Lehrer: How much are other decisions by the FDA to approve other medications or any other kinds of decisions by the FDA suddenly at risk if the plaintiffs, I guess, the plaintiffs are the ones against Mifepristone, if the plaintiffs ultimately win their case?

Emily Bazelon: It just blows an enormous hole in the FDA's authority and all of the reliance on the FDA is the national approver of drugs. That is our system in the United States. We have this agency, they're a very cautious agency. If anything, often people argue that they are too cautious about letting new drugs on the market. If plaintiffs can come in and there's a whole set of questions about whether these plaintiffs should even be in court, whether they have what's called standing to sue. That's part of this case.

If you look at the theory of both the District Court and of the Circuit, you applied that in a context outside of an abortion medication, you would really be changing how the whole pharmaceutical industry operates. One interesting part of this case was that last week 400 Big Pharma executives and investors wrote a letter just condemning this set of judicial orders because they said, "This is just not how American drug approval works in the United States. We need to rely on that approval process to bring drugs to market."

Brian Lehrer: Oh, now progressives have to say, "Go Big Pharma."

Emily Bazelon: [laughs] Well, think about it this way, Brian. There have to be rules that any set of companies can rely on in order to know what their costs are going to be, how things are going to work when they develop a new product. Whatever you think about Big Pharma, having rules that are even-handed and stable are important to the drug industry.

Brian Lehrer: Will this ultimately return to the Supreme Court?

Emily Bazelon: Yes, I think it absolutely will. Partly because the FDA's larger authority is at stake and the way we've been talking about, and also, because of this competing order from this federal judge in Washington State. These orders from Texas and Washington State are directly in conflict with each other, and only the Supreme Court can sort that out ultimately.

Brian Lehrer: For you as a Supreme Court watcher, is there any reason to think this is going to wind up any different from the Dobbs decision, which struck down Roe v. Wade?

Emily Bazelon: Well, here's what's really interesting legally. Dobbs was all about returning authority to restrict abortion or allow abortion to the states. That's the whole thing. [unintelligible 00:10:38]

Brian Lehrer: Let me jump in on that, Emily, because it wasn't, really. It was about returning it from the judicial system to the political sector so that it could be at the state level, it could be at the federal level. It's just that the judges who struck down Roe said the Constitution doesn't say anything one way or another about abortion, or am I wrong?

Emily Bazelon: No, you're right. I think maybe we're both right. Yes, Dobbs leaves room for Congress to pass a law one way or the other about abortion. In that sense, yes, you're absolutely right. Practically speaking, since Congress hasn't done anything, what Dobbs did was to return authority of the states. You're right that Alito talked about taking the courts and the Constitution out of the equation. He also talked about state voters having authority and passing the baton to them. This is not that, this is a national order.

Brian Lehrer: Certainly, the anti-abortion movement never mind what a court says officially, the justices or judges from the bench. The anti-abortion movement has used that rhetoric over the many years since Roe. "We should return this to the states." Because what Roe did was strike down particular state's ability to restrict abortion. The Supreme Court called it a constitutional right. They were striking down what states did, so the anti-abortion movement has been trying to say, "Return this to the states," whether or not that was their real goal. They wanted to return it to any political sector that could restrict abortion. They've been saying, "Return it to the states." That's why it's so lodged in people's brains?

Emily Bazelon: Yes. Return to the states. You're totally right that anti-abortion folks would love for Congress to also restrict or ban abortion. People who are in favor of abortion access are appealing to Congress to do something to protect it. You're right. We're talking about legislative power as opposed to judicial power. Okay, so let's think about what happens if the Supreme Court orders Mifepristone off the market or orders the FDA to stop mailing it. Well, that's a very big step for a court to take.

That's injecting the Supreme Court right back into the center of the equation. I suppose if the conservative justices do that, they could say, "Well, Congress, go ahead. We're not telling you that you can't pass a law making it clear that the FDA has the authority to allow Mifepristone," but the truth is, the FDA already has that authority and used that authority. It would be a really big step for the court to inject itself into the drug approval process that way.

Brian Lehrer: Is it too early to even speculate on, if this returns to the Supreme Court, that ultimately they're going to be weighing medical evidence, they're going to have medical experts on one side and medical experts on another side, debating whether Mifepristone has proven itself to be safe and effective over the 20 years since the FDA approved it?

Emily Bazelon: I guess so. What's crazy about that is that the Supreme Court has been trying to take itself out of questions like that. If you take Justice Alito's opinion on its face, the idea is, we don't want judges acting in this kind of capacity. Judges don't have the expertise for this. That's why they normally defer to agencies. The other thing I have to say is that the level of medical authority, the evidence is so completely on the side of approval of Mifepristone and its safety and effectiveness that like, yes, sure, the plaintiffs will line up someone to say the opposite, but the weight of the medical evidence is really on the side of the FDA.

Brian Lehrer: Let's take a phone call. I think Judy in Manhattan is saying, "The potential effects of restricting Mifepristone go even beyond access for women who might want a medication abortion." Judy, you're on WNYC with Emily Bazelon. Hi, Judy.

Judy: Hi, Brian. In the intro, you mentioned that this would affect women. This affects the economy of the United States. If a woman has to carry a child, and especially if she's in school, there is no way that she can continue on her career path, especially because we don't have childcare in this country, and she will be forced to become a mother at home. When you start multiplying the cases, after a while you see how it can affect the entire United States economy.

Brian Lehrer: Yes. Emily, you can comment on that. I don't know that we want to make moral judgments about people's basic rights on the basis of what the economic effect might theoretically be, but I don't know. Emily, have you ever heard that one before?

Emily Bazelon: There was a really interesting brief filed by a bunch of American historians in Dobbs and one of the things they did was show how much evidence there is that the availability of birth control and abortion has been really crucial to women's economic development, their professional success to the rates of women going to college and professional school and getting graduate degrees rising. Maybe that's part of what your caller is getting at.

Brian Lehrer: Yes, certainly that way. Anyone else? 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692 as we continue to parse the Supreme Court's ruling on Friday about Mifepristone and what might come next. We're also getting to get into the Justice Clarence Thomas conflict of interest controversy and the hearing taking place in Manhattan today by the House Judiciary Committee ostensibly and to crime in Manhattan, and the failures, as they will argue, of Manhattan DA Alvin Bragg, but, oh, does that happen to actually really be about the fact that a Manhattan grand jury just indicted Donald Trump?

Any of those three things, 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. In fact, let's take a break right here, and you can keep calling on Mifepristone and the Supreme Court. When we come back, we're going to turn the page right away and talk about Clarence Thomas. Stay with us.

[music]

Brian Lehrer on WNYC as we continue with Monday morning politics and Monday morning law with Emily Bazelon, staff writer for the New York Times Magazine, co-host of Slate's Political Gabfest podcast, Truman Capote fellow for creative writing and law at Yale Law School, and author of the bestselling book, Charged: The New Movement to transform American Prosecution and Mass Incarceration. Maybe that's why the House Judiciary Committee is holding an anti-Alvin Bragg hearing in Manhattan today.

As we said at the top, we're asking Emily to do a lot of explaining of things that are in the news and kind of complicated. For those of you who haven't read every word of 4 News organization's coverage of these complicated things, Emily's doing a lot of explaining here today. Next topic, the ProPublica investigation. I'm going to read their headline from the other day, "Billionaire, Harlan Crow, bought property from Clarence Thomas. The Justice didn't disclose the deal." What was this property and what would a Supreme Court justice be required or encouraged to disclose?

Emily Bazelon: Yes, [laughs] this property is where Clarence Thomas grew up. His mom lives there. This was a deal that appears to have been hidden. This is a string of properties in Savannah, Georgia, and, they were purchased for over $130,000, but you can't really tell that. You can't tell that at all from what Thomas has disclosed. You have Harlan Crow, this, close friend of Thomas's owning the house where Thomas's mom is living, and a lot of development going on there.

You have no acknowledgment from Thomas that this deal happened. We have this law called the Ethics and Government Act, which passed after Watergate, and the idea was that elected officials and also judges, Supreme Court Justices, were supposed to disclose details of most real estate sales that are over $1,000, and Thomas did not do that here.

Brian Lehrer: I'm going to read from the ProPublica story here a little bit. "Thomas never disclosed his sale of the Savannah properties that appears to be a violation of the law. Four ethics law experts told ProPublica the disclosure form Thomas filed for that year also had a space to report the identity of the buyer in any private transactions such as a real estate deal, that space is blank." Is there suspicion about the relationship between Thomas and this Developer, Harlan Crow, and something Crow or other interest that he represents wanting something from the Supreme Court? Is that where the rubber meets the road in terms of the public interest?

Emily Bazelon: I think we don't know and that itself is a problem. ProPublica published another story first which was all about these super fancy vacations and private jet flights that Thomas had taken with Crow that he also didn't disclose were worth a lot of money. Thomas responding to that said, "Oh, this is just a friend of mine and I consulted with colleagues when I joined the court and I was told that if I'm a guest of a friend, that's not something I need to report."

That seems also at odds with the Ethics and Government Act. The issue here is twofold. Was Harlan Crow getting something specific from Justice Thomas in terms of a particular ruling? We don't have evidence of that, but is there an appearance of impropriety here and of a relationship where we can't trace the influence and the public didn't know about all this money and all these gifts being lavished on Justice Thomas? Yes, that definitely appears to be the case.

Brian Lehrer: Are there other cases in Supreme Court history that set a precedent for either what justices are supposed to do or for any discipline or in the extreme case removal of a justice who violates these kinds of ethical standards?

Emily Bazelon: Yes, actually. Justice Abe Fortas in the '60s resigned from the Supreme Court because he had supposedly taken money from a financier. At the time it was like $20,000. This was in 1969. What happened in that case was facing an investigation. Fortas said, "I will leave the court." There was a kind of acknowledgment there that there was something to be ashamed of, that you're not supposed to be taking payments like this.

Maybe you have a perfectly fine explanation for it, but that's just not what we expect from the level of impartiality and unimpeachable integrity that we want from Supreme Court justices. I think that's the best precedent here. We have obviously not seen any indication that Clarence Thomas is planning to resign.

Brian Lehrer: Tell me again, how did Fortas wind up getting removed from the court? Did he resign because he was humiliated by the public revelations and there was pressure or did the Chief Justice at the time remove him or was he impeached by the Senate? How did that actually work?

Emily Bazelon: Fortas, he was a Democratic appointee. He took $20,000 to consult for a foundation that was working on civil rights and religious freedom. It used to be that this was not so unusual. There were other justices on both sides of the aisle who had paid positions at foundations. The particular businessman who retained Fortas, this guy Louis Wolfson, was being investigated by the Justice Department for Financial Improprieties and he eventually got convicted.

That was a cloud that was hanging over Justice Fortas. Once there was reporting on these ties to this foundation, even though he'd returned the money, there was a scandal. That scandal led to Fortas's resignation.

Brian Lehrer: Is there a role for Chief Justice Roberts here with respect to a public reaction or an action of any kind regarding Justice Thomas?

Emily Bazelon: Poor Chief Justice Roberts. [chuckles] I have to say, I think you have to pity him in all of this. Because Clarence Thomas, his wife Ginni Thomas who's so tied to the right-wing clauses and the Republican Party, they have just been a thorn in the side of Chief Justice Roberts making the court look bad for a while now. The issue here is that the Supreme Court is not bound by the code of ethical conduct that bounds other judges.

They set their own rules. There's really no way other than embarrassment or changing those rules that Roberts can address this. I do think that there should be pressure on the justices to bind themselves to the code of judicial conduct and figure out a way to make it enforceable. It's possible that's happening inside the court, but we have not heard about that.

What you have here yet again, is a kind of embarrassment. I think a real stain on the Supreme Court that makes Americans question the integrity of the whole institution. We've obviously seen these declining public approval ratings about the court for a while now and I think it really breeds citizens with the American public that the justices are any different from other kinds of politicians.

Brian Lehrer: There was a Jamelle Bouie column in the New York Times the other day and I'm getting into real historical weeds here. Tell me if I'm going beyond even your knowledge base, which you have asked, about right near the beginning of the history of the country, Justice Samuel Chase, I believe it was, who some people wanted to remove because he just became too political as a Supreme Court justice. Are you familiar with that? Because there's echoes of Clarence Thomas in that story, the way I read it.

Emily Bazelon: Yes. I can't remember the details of the story about Justice Chase, but it is part of this whole-- This way in which we see how the court has changed. I think that in the time of Justice Chase and this early era of the court, there was also politicization going on. There's this famous episode where Thomas Jefferson gets voted into office and right before he becomes the president, his opponents pack the court.

They literally just add a bunch of positions, not to the Supreme Court itself, but to the Circuit Courts, which were the appellate courts. They at the last minute try to jam in all these appointees and they're basically just trying to take away the authority of Thomas Jefferson and control the courts. It's like the former Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell. It's that kind of move. We've had other eras in America where the courts have been politicized in this sense. I don't think that's really an excuse for Thomas's behavior here.

Brian Lehrer: The Ginni Thomas role here, this bleeds into what's going to be our third topic when we get to it, which is the Republicans in Congress going after Alvin Bragg just after a grand jury that reports to Bragg indicted Donald Trump. What a coincidence! Trump himself, as I'm sure you've seen, has gone after Bragg's wife and of course, the DA and other people are concerned that this is a public safety risk and beyond the [unintelligible 00:27:14] anyway, to criticize somebody's wife.

Allegedly because she has done some political work with Kamala Harris and things like that. Of course, if you raise Ginni Thomas to any of these particular Republicans, they're going to say, "Hands off, that's out of bounds. That's just a spouse. That's not the justice." Is there at least a double standard here that we should acknowledge?

Emily Bazelon: I think the other thing about Ginni Thomas that it's so striking is this case in which Thomas did not accuse himself from deciding a matter related to January 6th. There was this question before the Supreme Court, can the January 6th investigators get access to a whole bunch of text messages from people like the former White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows?

It was 8-1, Justice Clarence Thomas was the only dissenter from allowing this access. Then the texts get revealed and it turns out they include texts from his wife. That is a way in which I think it's entirely legitimate to question how someone's personal ties and spousal ties are affecting their rulings and why Justice Thomas did not take himself out of that case, given that his wife's texts were directly an issue?

On other fronts, you might get nervous about making public officials responsible for the work of their spouses. Because we don't want to discourage two career couples from having both people be able to participate in advance. That case involving the Thomas's and that 8-1 ruling, I think is really problematic.

Brian Lehrer: We're going to get to DA Bragg and the House Judiciary Committee Hearing in Manhattan today. We have a lot of calls coming in still on the Supreme Court and the Mifepristone case. Let's take a couple of those because people really want to talk about that as it continues to unfold after the Supreme Court's preliminary, temporary along the way tentative, I think folks who get the idea, this is not the final word, ruling on Friday. Deborah in the Hudson Valley you're on WNYC. Hi, Deborah.

Deborah: Hi, thank you for taking my call. I'm a huge Emily Bazelon's fan. It seems to me that the Mifepristone ruling is such a blatant [unintelligible 00:29:35] The conservative argument about the drug is not that it isn't safe and effective, but that it is safe and effective and maybe too safe and effective. It creates safe abortions. Am I missing something there?

Emily Bazelon: Well, you're right. That, I think, is the underlying agendas to end abortion and that the abortion pills have been hugely important, especially since Dobbs and continuing access that women have to abortion. When they go to court, what the anti-abortion plaintiffs argue is that the drugs are unsafe. There's the overriding purpose here, and I think you're ready to see that. I think abortion opponents would be very clear about that. The whole idea here is that abortion is wrong and they're trying to end it. The way that you do that in this particular case, to make your legal claim try to stick is to argue that Mifepristone is not safe, contrary to the medical evidence.

Brian Lehrer: Maggie in Brooklyn, you're on WNYC. Hi, Maggie.

Maggie: Hi. Thank you, Brian. Emily, I wonder why no one, in talking about the abort-- I guess, maybe other countries just don't count. In America, nobody ever mentions that abortion is being restricted right now in many ways for women who are having a health crisis with miscarriages and because of this concept of a heartbeat, even though up to a certain stage there is no heart. Doctors are not giving the medical care that women need during miscarriage and send them home bleeding to basically wait until that 'heartbeat' stops.

In the interim, they can often become septic. In Ireland that was the straw that broke the camel's back when a woman who, with her partner, were very much looking forward to having a child. She started miscarrying because they had a constitutional amendment in Ireland prohibiting abortion. They sent her home. She became septic and died along with her baby.

This whole idea that you can prohibit abortions after a certain point in time and that I guess, basically, slutty women will shape up and stop having sex is just belied by the experience in so many other countries. I am just hoping that it doesn't come to many women dying before this country says, "Oh, geez, maybe this is a bridge too far. Why is it never mentioned?

Brian Lehrer: Maggie, thank you. Emily, other countries context. Some people really resist bringing in other countries' judiciary experiences. Of course, Maggie's going beyond that to medical experiences as a factor, perhaps in our own Supreme Court's assessment of this case.

Emily Bazelon: I actually happen to be in Argentina right now in Buenos Aires doing some reporting because Argentina, with a piece of national legislation legalized abortion up to 14 weeks in 2020. I was just really interested in being in a country where they have gone in the opposite direction from the United States and trying to understand how that happened. I'm really interested in these kinds of international questions. One more point about the United States, and I've been hearing this from people here, the changes since Dobbs are making abortion more uncomfortable, more anxiety-provoking, later term, more dangerous for American women.

That's not the intent, I think, of some abortion opponents who truly believe that abortion is immoral or against their religious principles. The effect of making it harder to get Mifepristone is that you take away the drug that makes it easier to have what is effectively an induced miscarriage. The effect of closing abortion clinics is you make people drive farther. You delay abortions into the second trimester. We're hearing that from providers. There's just a lot of pain and suffering that is attached to the end of Roe v. Wade. I share your view, Maggie, that it, obviously, would be very tragic for people to have to die in order for that to change. I really hope that that is not what we are going to see.

Brian Lehrer: Also related to Maggie's call and her urgent plea, Mifepristone as well as the other abortion pill, which isn't in the legal crosshairs quite yet, misoprostol are also used in cases of miscarriage to help that go as well as it could possibly go.

Emily Bazelon: Yes, absolutely. You're right. Maggie started by talking about miscarriage management and how important it is for women to be able to freely go to the ER or go to their doctor if they need to, and not worry that they're going to be blamed for their miscarriage or that they're going to have to go home and left to be subject to infection the way you were describing. Because a doctor is afraid to treat someone because there is still a heartbeat or for whatever other reason.

We are seeing those cases in some of the states with abortion bans with really poor care and a real conflict between a doctor's Hippocratic oath to do no harm and what the law is requiring, which is proof that the fetus has died before they can treat.

Brian Lehrer: In our last five minutes, let's turn to the hearing by the House Judiciary Committee in Manhattan today, ostensibly, about crime in the borough of Manhattan and the role of DA Alvin Bragg. Everybody thinks this is really because Bragg just presided over a grand jury that indicted Donald Trump this month. For you, Emily, I wonder if you're watching this hearing with a particular eye because I'll remind people that you wrote the book that was a best-seller, Charged: The New Movement to Transform American Prosecution and End Mass Incarceration.

Here's Alvin Bragg, who's one of those progressive prosecutors who's trying to fight crime and mass incarceration at the same time. He's already been in the political crosshairs. He compared himself to Willie Horton for the way that Republican gubernatorial candidate in New York, Lee Zeldin, used him during his campaign last year. Now here comes Jim Jordan and the House Judiciary Committee trying to say that Alvin Bragg is causing crime in New York. "Oh, by the way, he shouldn't have indicted Donald Trump," even though they may not say that last part out loud. For you who wrote a book on progressive prosecutors, how are you watching this chapter in the Alvin Bragg saga?

Emily Bazelon: I think you're right, and it's obvious that this focus on Bragg is because of his prosecution of Trump. However, you're also right that there's this larger move going on to try to discredit progressive prosecutors blaming them, whether it's true or not for rises in crime or for particularly notorious crimes in the cities where they are elected. Crime is actually down in Manhattan from last year to this year by about 2.4%, but it certainly rose during the coronavirus and we don't know exactly why. If you are someone on the right just trying to discredit the whole project of sending fewer people to prison, then you blame the progressive prosecutor no matter what.

The crime rise we saw during the pandemic was nationwide. There are cities with Republican officials same as cities with liberal Democrats where crime rose. It doesn't really matter because this is such a good punching bag or at least it has been historically for law and order conservatives. We're seeing that playbook ruled out today in Congress.

Brian Lehrer: DA Bragg, I see, has filed a lawsuit against Jim Jordan, the Chair of the House Judiciary Committee. Have you looked at that enough to know why Bragg is going to court against political process that's targeting him?

Emily Bazelon: Jordan has been trying to-- What Bragg sees is interfere with the prosecution by demanding documents and Bragg's communications while this prosecution is ongoing. That is not the way it usually works. Once you brought an indictment in a prosecutor's office, you're supposed to be able to work internally on that prosecution without having to disclose what you're working on and how you're talking about it, but Jordan has this theory that since there are some federal funds being used to prosecute this case, that Congress has oversight of it in real-time. He wants these documents now. That's another subtext for this hearing today.

Brian Lehrer: Emily Bazelon, staff writer for the New York Times Magazine, co-host of Slate's Political Gabfest podcast, Truman Capote fellow for creative writing and law at Yale Law School, and yes, author of that book, Charge: The New Movement to Transform American Prosecution and End Mass Incarceration. As I said at the beginning, I know you jumped on last minute with us today as we had some moving parts. Now I know you did it from Argentina, where you're on a reporting trip. Amazingly, I think we had better line quality from Argentina than we do half the time from Brooklyn. I so appreciate it, Emily. Thank you very much for all your wisdom and of course, your time today.

Emily Bazelon: My pleasure. Thanks for having me, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. A lot more to come. Stay tuned.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.