A high school junior — WNYC is calling her Vanessa — arrived in Brentwood, Long Island, two years ago as an unaccompanied minor from Central America. Then she spent a month in the immigration wing of a county jail in New Jersey, accused of being affiliated with the gang known as MS-13.

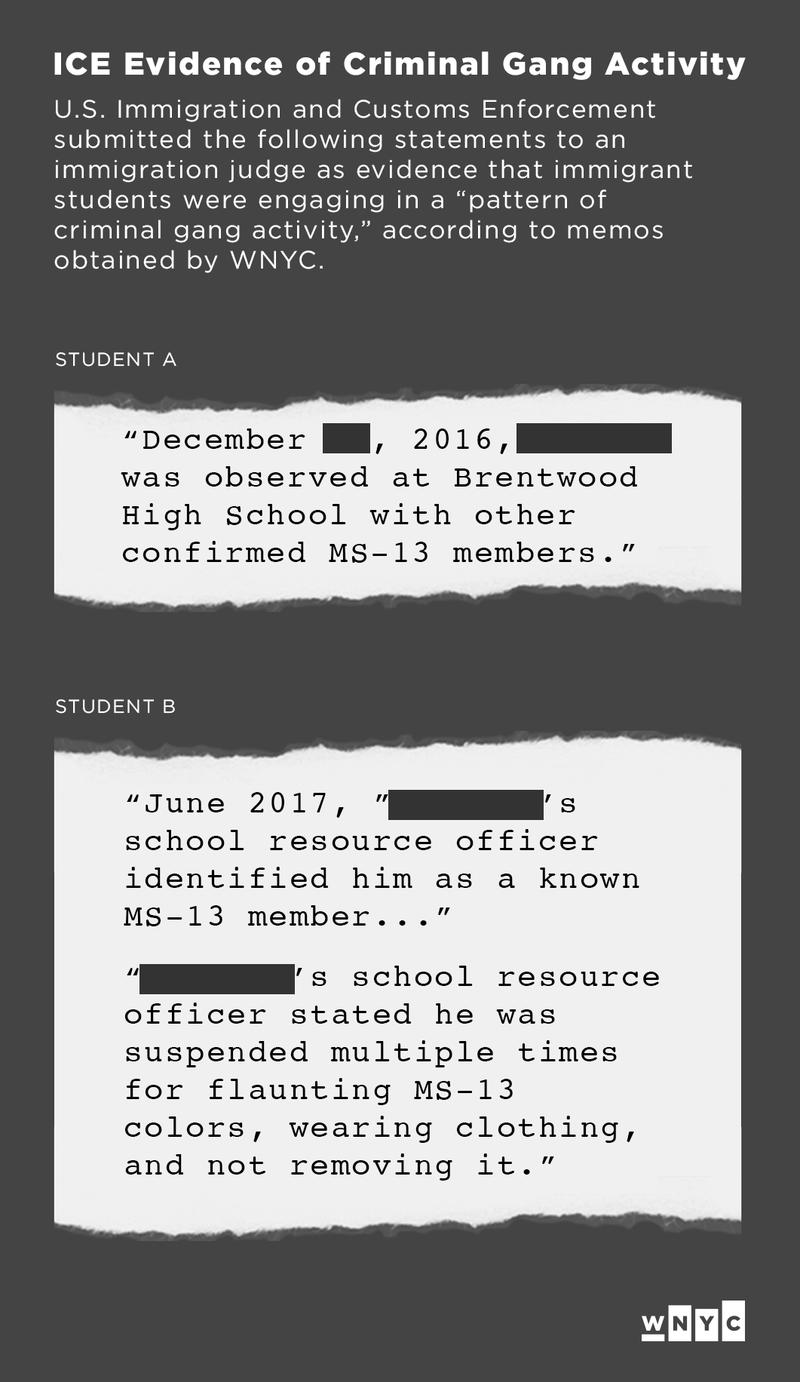

The evidence used to detain her: she was seen speaking with suspected MS-13 members at school.

It did not pass muster with the court, but the girl’s lawyer said the incident raised questions about how much intelligence was being obtained from public schools. Police officials did not disclose how they coordinate with police officers assigned to schools, called school resource officers, on gang investigations, but students' families and advocates also have raised concerns about possible in-school surveillance and information sharing.

MS-13 has been tied to 17 murders in Suffolk County since 2016; President Donald Trump recently visited the area vowing to eradicate the group, which the federal government has made a priority since 2005.

Vanessa's lawyer, Bryan Johnson, told WNYC that several of his high school student clients have been picked up by immigration officials and accused of gang membership. The charges hinge on things like the clothes they wear to school, the classmates they speak to and what they're suspended for, according to federal immigration documents obtained by WNYC.

"Anyone that they can even remotely link to MS-13: They have a family member who was a gang member or they were seen sitting in class next to someone who was a gang member, they’re fair game," Johnson said.

Critics of the latest sweep of arrests and detentions said some information, such as student suspension records, should be protected by federal privacy law. Other evidence recently came under fire from the New York Civil Liberties Union for relying on "questionable" affiliations and actions to claim gang activity.

"None of them have been convicted of crimes, keep that in mind," Johnson said of his clients. "They have no criminal history."

In Vanessa's case, immigration officials said she was "observed at Brentwood High School with other confirmed MS-13 members." That was her "pattern of criminal gang activity," according to the memo.

The memo read: "In light of [Vanessa’s] affiliation to a violent street gang, she should not be afforded any type of immigration services, relief, benefit or otherwise released from custody pending the outcome of removal proceedings."

But a judge released Vanessa from detention. She said there wasn't enough to support the fact that she is a gang member.

"There’s nothing else there really other than she’s been seen in the presence of gang members," the judge said in court. "I unfortunately imagine the Brentwood High School [has gang members]."

Releasing Vanessa on bond meant the judge didn’t see her as a danger or a flight risk. But she still has an open removal case, meaning she can face deportation. Vanessa came to the United States from El Salvador at age 16. She traveled by foot; the journey took her a month and a half.

Now, she said, she doesn’t want to go back to Brentwood High School for her senior year.

"I’m scared to go back," she said in Spanish. "Look at everything I went through, just for attending that school."

Johnson said another of his clients was suspended from Huntington High School for drawing bull horns on a school calculator. The symbol is associated with the MS-13 gang, but could also be part of the school mascot, the Blue Devils. That client is still in immigration detention.

The spokesman for one school dictrict, Felix Adayeye with the Brentwood School District, said it does not share student suspension information with police because of a federal law called the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, which protects the privacy of student records. But he pointed out that school resource officers, who are employed by the police department, are inside schools.

"School resource officers do not have access to student information, but they do have access to students," Adeyeye said. "And they do observe quite a few things."

WNYC asked Suffolk County Police Commissioner Timothy Sini how school suspensions ended up in the hands of immigration officials.

"There are a number of ways,” Sini said. “And kudos to school resource officers for being diligent."

Police said they believed there were about 400 confirmed MS-13 gang members in Suffolk County. But they cannot arrest people just for being in a gang — they have to be suspected of committing a crime.

As a result, Sini said, a police officer is assigned to closely watch individual suspected gang members and wait for them to commit any petty offense. If a suspected gang member is in the country without proper documents, police notify immigration officials.

Homeland Security launched “Operation Matador” this past May, after the murdered teens on Long Island were found hacked to death by machetes. The effort is focused on eradicating MS-13 in New York and Long Island, said Angel Melendez, the Special Agent in Charge for ICE’s Homeland Security Investigations in New York. The name of the operation refers to a bull fight.

"The third stage is when ‘el Matador’ comes in to finish,” Melendez said. “And that’s our commitment, to finish."

He said he was confident everyone they detained or arrested or identified as gang members were MS-13 — even if a judge wasn’t convinced.

"My agent’s job is to present evidence. What is determined after that, that's beyond my control, and we continue to do what we do," Melendez said. "And most of these cases I'm pretty sure that many of them will fall back and we will be arresting them again."