On Martin Luther King Day, an emotional Harry Pangemanan took the stage in a high school auditorium in his adopted hometown of Highland Park, NJ. He was greeted with hollers, cheers and a bouquet of flowers as he received the Martin Luther King Humanitarian Award for helping to rebuild more than 200 homes on the Jersey Shore after Sandy.

Just 10 days later, Pangemanan was pulling out of his driveway, taking his two daughters to school, when he saw what he believed to be immigration officers coming to arrest him and deport him to his native Indonesia — a country he last set foot in 25 years ago.

"As a human being, you’re asking, 'Why?'" Pangemanan said.

Pangemanan believes he avoided detention because he called his pastor and best friend, Seth Kaper-Dale, who rushed to his house. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers left, and Kaper-Dale took Pangemanan to their church, where he moved in with his family and other Indonesians hoping to avoid deportation. Churches are considered by immigration advocates to be "sanctuaries" where immigrants are protected from deportation, and authorities have avoided making arrests at houses of worship.

Pangemanan spent more than a week in sanctuary before the American Civil Liberties Union filed a class action lawsuit on behalf of Pangemanan and other Indonesians in New Jersey who years ago overstayed their visas and lack legal status in the U.S. The ACLU argued that the immigration cases should be reviewed before any deportations proceed, given a recent uptick in violence against Christians in Indonesia, the largest Muslim nation in the world.

U.S. District Court Judge Esther Salas wasted no time on Friday evening. She issued a restraining order, temporarily barring ICE from deporting the Indonesians until at least March, when a court hearing is scheduled.

And so this past weekend, Pangemanan and others in sanctuary left the Reformed Church of Highland Park, where Pangemanan is a lay leader. And three Indonesian men currently in detention in Newark and Elizabeth could soon be released.

In a similar case last year, a federal judge in Boston temporarily blocked the deportation of Indonesian Christians from New Hampshire.

Since President Trump signed an executive order last year mandating immigration officers detain anyone suspected of immigration violations, regardless of criminal history, Indonesian Christians in Central New Jersey have felt targeted. At least six ethnic Chinese Indonesian Christians were deported, and two families left on their own, under pressure.

The Indonesians' predicament was highlighted in a visit to the church last month from Gov. Phil Murphy, who expressed support for them. That day, the homes of Pangemanan and another Indonesian, Arthur Jemmy, were ransacked and burglarized while they were living in sanctuary. Money, jewelry and the families' passports were reported stolen.

Kaper-Dale said ICE could’ve been involved, but an agency spokesman called that patently false and said the vandalism was unfortunate.

Pangemanan's wife and daughters were not home at the time, but they were shaken up. Clothes in his daughters’ room were strewn all over. His 11-year-old was especially upset that her own savings were stolen. "Some from the piggy bank, some from the envelope, some from her purse," Pangemanan said.

"Poppa," his daughter told him. "I don’t have any safe space for me, except for my church."

Jemmy, who lived in sanctuary from October until last weekend, said he fears a return to Indonesia. He said he left nearly two decades ago after witnessing a preacher decapitated by a Muslim mob during a service.

Jemmy's home in Edison was also found burglarized at about the same time as Pangemanan’s. "If someone do that on purpose, God bless them," Jemmy said. "I just pray for them."

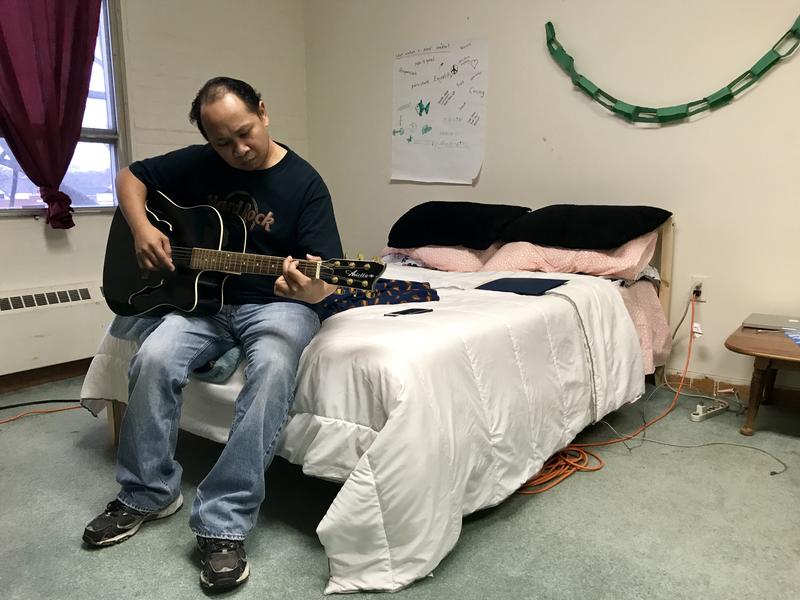

Jemmy lived in the church's Classroom 204, where a colorful mural on the wall kept him smiling, he said. Every Sunday, he and his wife packed up their belongings so the room could be used for Sunday School. He passed the time by playing with Pangemanan’s daughters, strumming his guitar and helping out in a church cafe run by refugees.

There are an estimated 2,000 Indonesian Christians of Chinese descent living in the Middlesex County area. Many arrived in the 1990's fleeing religious persecution, and they overstayed tourist visas. Those who applied for asylum said they did not know about a requirement that they apply within one year of arrival. They worked, mostly blue-collar jobs, and started eight Christian congregations. Some bought homes, married and had American-citizen children.

But after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11th, the Justice Department required men from Muslim nations — even if they weren't Muslim — to register with the government. Kaper-Dale told the Indonesian parishioners in his church to follow the government's rules. But that put them on the immigration officers' radar, making them what Kaper-Dale considers low-hanging fruit for deportation.

"That’s the way they’re getting to their numbers is just by destroying the lives of black and brown families who have tricky immigration situations," Kaper-Dale said of ICE immigration officers.

A spokesman for ICE, Emilio Dabul, said the agency has no deportation quotas and its arrests are not directed at a particular community. The spokesman would not comment on Pangemanan's case but he said the other recent detentions came as a result of "targeted enforcement actions."

The Indonesians' status has long been a problem. Pangemanan actually moved into sanctuary at the church once before — he was there when Sandy hit in 2012, which is how he became a kind of uber-volunteer. "He coordinated incredible disaster relief while stuck in this building," Kaper-Dale said.

Pangemanan ran disaster relief operations until Kaper-Dale was able to strike a deal with the Obama Administration: Indonesian Christians would be allowed to live freely as long as they stayed out of trouble and checked in annually with ICE. Pangemanan went on to become the church's minister of disaster relief, learning how to hang drywall and manage construction crews. He helped to rebuild more than 200 homes destroyed by Sandy.

Now, that deal with the federal government is apparently off. So the Indonesians and their advocates hope the courts allow them to stay in the country.