NYPR Archives & Preservation

NYPR Archives & Preservation

Long Before C-SPAN, WNYC was Airing the Legislative Process

The 1938-1939 WNYC City Council programs were the first time in history that the proceedings of an entire legislative session were broadcast to the electorate. Letters to the station called the broadcasts instructive, entertaining, exciting, and a step forward in good government. A WNYC postcard survey determined that a million New Yorkers tuned each week to hear the New York Council session. A bevy of civics groups endorsed the broadcasts with the Women's City Club calling them, "the best education for citizenship." The Times gushed it was, "one of the best shows in the city, appealing in equal degree to the studio audience in City Hall and the radio audience over WNYC."[1]

The previous Aldermanic meetings generally had ten to twenty people in the visitor's gallery. The newly broadcast City Council meetings were now generating "500 to 600 persons who waited patiently in line for admission to the overcrowded councilmanic chamber."[2] The city's paper of record reported:

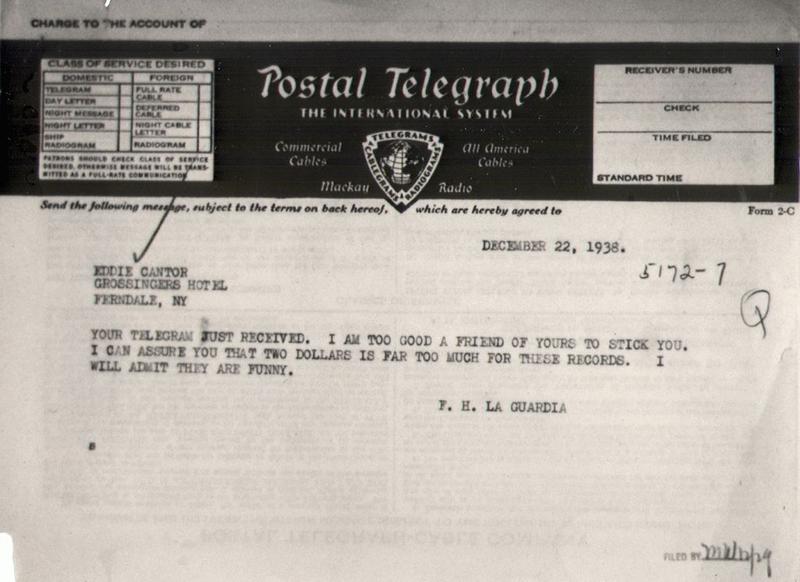

At times the Council broadcasts became so amusing that people left their radios and flocked to City Hall to see the fun. Borough President James J. Lyons of the Bronx even suggested formally that the proceedings be put on permanent records for their amusement value.[3]

Overnight in the City of New York, thousands of housewives, business people and others who listened to the radio during the day, had the welcome relief of an interesting, useful radio broadcast of their own government in action to take the place of the usual soap opera which pervaded the air at that hour. No Hooper rating is available, but judging from the thousands of letters and postcards which deluged Station WNYC when the Democratic majority threatened to cut off the broadcasts, it is fair to say that several hundred thousand citizens listened in daily. In fact, the city received several lucrative offers from private sponsors for the exclusive privilege of broadcasting the Council sessions.[6]

The broadcasts continued “gavel-to-gavel,” without editing or censorship, for two years. Then, without explanation or justification, Democrats, in opposition to the Republican La Guardia administration, pushed through a resolution prohibiting broadcast equipment on the chamber floor and put the kibosh on the freewheeling transmission.

On the day of the vote (January 16, 1940) WNYC's Chief Engineer Isaac Brimberg arrived at the City Council Chamber with his equipment and was politely, but firmly, refused entry by the legislative body's sergeant-at-arms. The stormy two-hour debate that followed, no doubt, would have been great radio. Instead WNYC broadcast a luncheon for Finnish war relief from the Hotel Commodore. It was a poor substitute, and little solace for our civic-minded listeners.

If the old Board of Aldermen had taken 135 years to make fools of themselves, the Council had accomplished the same result in two years...I tuned in on a couple of those broadcasts last year and what I heard made me blush. And when a former Alderman blushes -- that's something.[7]

The Brooklyn Eagle's radio columnist Jo Ranson wrote a post-mortem for the broadcasts beginning with: "They went and scuttled the best Tuesday afternoon feature on the air. Shame on them!" Councilman Michael Quill of the Bronx was named "the best quipmaker," and the WNYC engineering staff, he noted, called B. Charney Vladeck "the most dramatic personality for speaking cooly at the hottest sessions."

Ranson also recalled how the broadcasts kept WNYC's engineers on their toes, moving mics and constantly 'riding gain' on the volume control as they jerked from the soft-spoken representatives to "frenzied orators." In addition, there was Councilman Abner C. Surpless of Brooklyn, who always addressed the body with a cigar in his mouth, and Robert K. Strauss of Manhattan, whose peripatetic delivery required two microphones to capture. The inability to stand still was also a factor with Mayor La Guardia and that the microphones, which he had a habit of shoving aside, had to be lowered immediately to accommodate his diminutive stature. According to Ranson, the "hottest and longest" broadcast session was on the 1939 budget, airing for nearly 21 hours straight hours and included Newbold Morris threatening to punch Bronx councilman Charles E. Keegan in the nose. [10]

You can listen to a rare surviving example of a council debate from March 8, 1938, above on a resolution to investigate WNYC. Some of the accents are classic!

And why, you may ask, did they want to investigate WNYC? Please see: Communist Propaganda or Capitalist Commercial? A 1930s WNYC Broadcast is Mired in Controversy.

_______________________________________________

[1] "Council to Debate Broadcasts Today," The New York Times, January 16, 1940, pg. 25.

[2] Belous, Charles, Faith in Fusion, Vantage Press, 1951, pg. 57.

[3] "City Radio May Lose Most Popular Program; Council Democrats Move to End Broadcasts," The New York Times, January 5, 1940, pg. 16.

[4] Goldman, Ralph M., The Future Catches Up, iUniverse, 2002, p. 29.

[5] WNYC Masterwork Bulletin, January 1939. pg. 2.

[6] Ibid., Belous, pgs. 56-57.

[7] "WNYC Broadcasts Banned by Council," The New York Times, January 17, 1940, pg. 27.

[8] "Council Tories Ban Radio Broadcasts of Proceedings," Daily Worker, January 17, 1940, pg. 4.

[9] "Penalties Urged in the Wagner Act," The New York Times, January 14, 1940, pg. 7.

[10] Ranson, Jo, "Council's Radio Fans Miss Weekly 'Shows,' " The Booklyn Eagle, January 21, 1940, pg. 14A.

Audio courtesy of the New York City Municipal Archives.