NYPR Archives & Preservation

NYPR Archives & Preservation

The New York City Landmarks Law: Saving the Past for Half Century

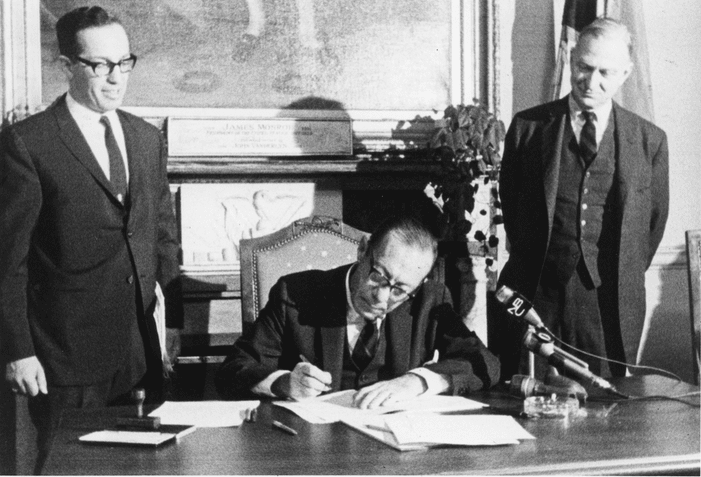

The Landmarks Preservation Commission was born 53 years ago this week, on April 22, 1962 with Municipal Art Society of New York (MAS) member Geoffrey Platt as Chairman. However, it was not until Mayor Wagner signed the Landmarks bill into law three years later, on April 19, 1965 that the Commission became a city agency with legal authority. When Platt sat down for this interview with Seymour Siegel on WNYC’s City Close-up in November 1964, the Commission was, in Platt’s words, “purely an advisory body.”

Of course, the history behind this groundbreaking legislation—the first historic preservation law of its kind—goes back many more years. Contrary to popular belief, the preservation movement and the desire for Landmarks legislation were not born out of the destruction and rubble of the original Penn Station. As far back as 1951, Municipal Art Society of New York (MAS) President Edgar I. Williams declared to the MAS membership:

“The accumulated evidence that New York’s architectural and historic monuments must be protected by direct action suggests that the Municipal Art Society take the lead in nominating structures for preservation. The controversy over Castle Clinton made many civic-minded citizens aware of the need for intelligent protection of such monuments, and more recently the destruction of the Rhinelander houses, St. Nicholas’ Church and the Ritz Carlton building have emphasized the desirability of an immediate expression of opinion on this important subject.”[1]

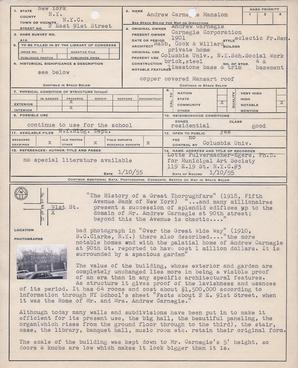

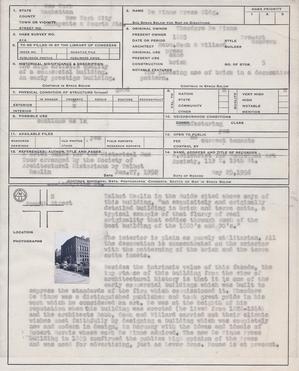

By 1953, through its Committee on Historic Sites, Monuments, and Structures and the work of its members, MAS assembled an Index of Architecturally Historic Buildings that it sought to preserve. The following year, MAS began to survey and document all of the buildings and structures on its Index.

Architectural historian and MAS board member Agnes Gilchrist spearheaded the project to document the MAS Index. In addition, at a board meeting in September 1955 she “advanced the suggestion of a ‘walking tour’ for the members of the Society” to educate and raise awareness about historic buildings. The first MAS walking tour occurred in 1956, the same year that the New York State Legislature passed the “Bard Act,” named after the lawyer, curmudgeon, and MAS board member, Albert S. Bard. “The Bard Act provided localities across New York State the authority they needed to regulate the built environment based on aesthetics, and was the New York State legislation that enabled the creation of a New York City Landmarks Law.”[2]

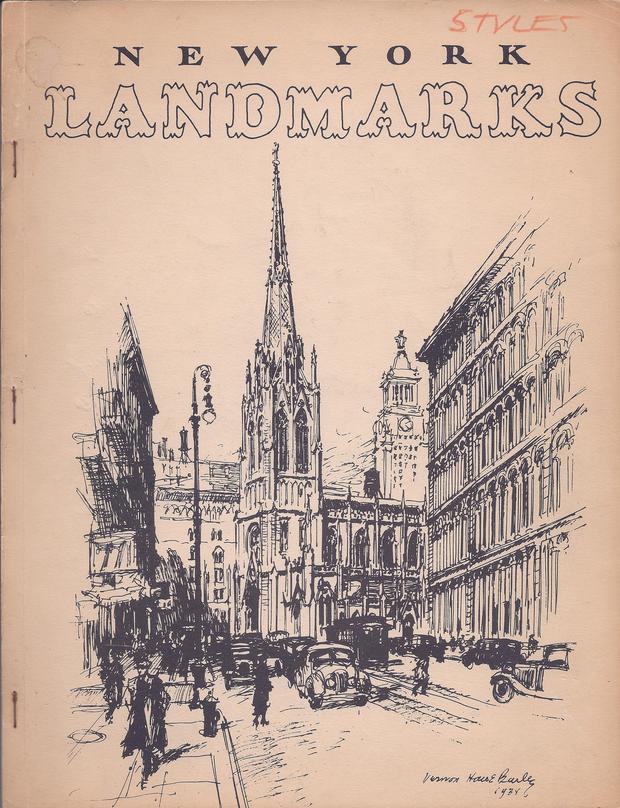

In January 1957 MAS published the first edition of New York Landmarks: Index of Architecturally Historic Structures in New York City that expanded on its 1951 list.

This eventually grew into the 1963 publication of Alan Burnham’s New York Landmarks: A Study and Index of Architecturally Notable Structures in Greater New York, published by Wesleyan University Press under the auspices of the Municipal Art Society. With the razing of Penn Station as a background, the book helped rally the preservation movement in New York City. It is also the book Platt cites and uses as a reference during the City Close-up interview.

It’s hard to remember today—with 1,347 individual landmarks, 117 interior landmarks, and 10 scenic landmarks across the five boroughs—that at the time of its passage, New York’s landmarks preservation law was a truly revolutionary concept. It would serve as a model for similar laws that were enacted around the country and forever change the way cities treat historic spaces.

________________________________

[1] See Anthony Wood’s Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect A City’s Landmarks (Routledge, 2007)

[2] For more information, see the NY Preservation Archive Project.