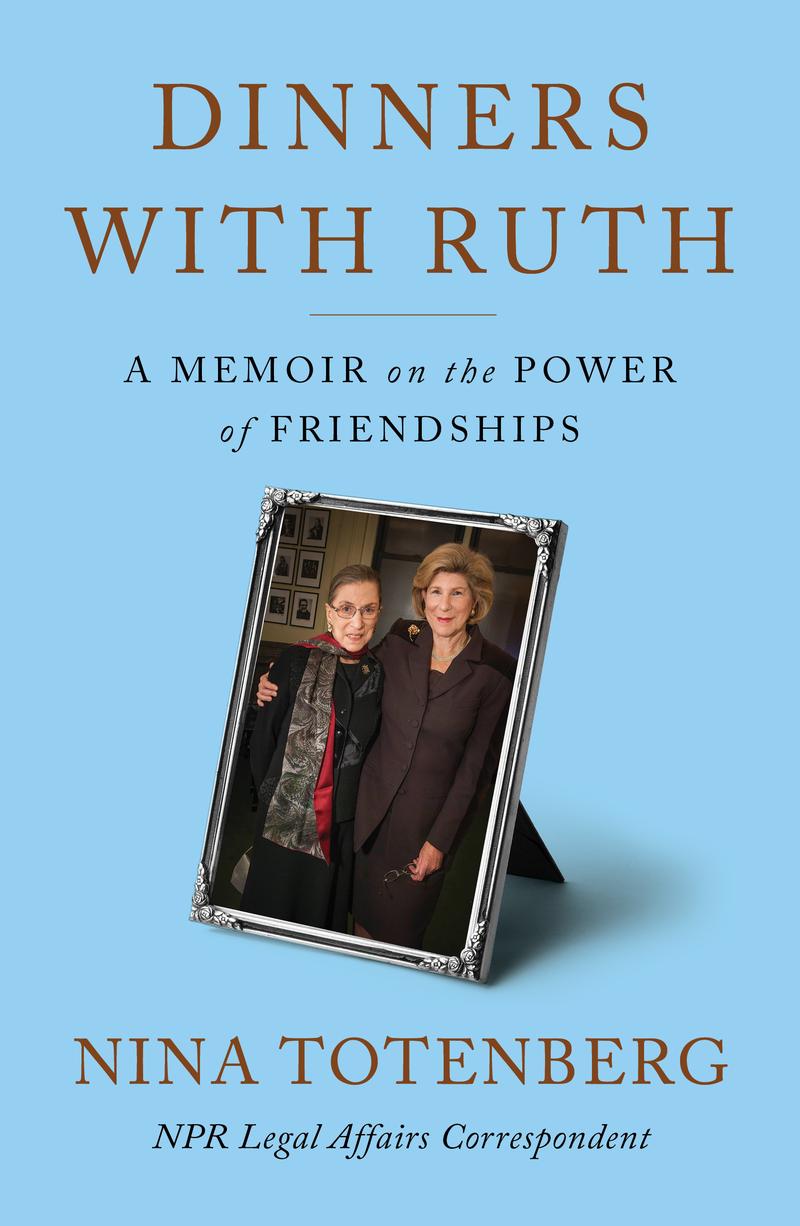

( Simon & Schuster, 2022 / Courtesy of the publisher )

Nina Totenberg, NPR legal correspondent and the author of Dinners with Ruth: A Memoir on the Power of Friendships (Simon & Schuster, 2022), looks back on her 50-year friendship with the woman who would become a Supreme Court Justice and how they each fought to overcome barriers and face personal challenges.

Brian Lehrer: It's the Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again everyone. With us now, NPR Legal Affairs Correspondent, Nina Totenberg, who has a beautiful new book called Dinners With Ruth. As you probably don't need to be told, those dinners were with Supreme Court Justice, Ruth Bader Ginsburg. As you may not know, their first conversation was four years before Nina was hired by NPR, which would put her 22 years before Ginsburg joined the Supreme Court.

The book can give you a glimpse of their particular friendship, maybe also about Ginsburg and abortion rights, which I think she thought could have been established by the court on a sturdier foundation than Roe v. Wade. We'll ask Nina about that, but also about how Nina's approach to journalism comes with getting to know supreme court justices as people, not just as justices with their opinions on a page or as representatives of certain idiologies.

You can learn about Nina's friendships, not just with Ruth Bader Ginsburg in this book, but also NPR's Cokie Roberts, and Linda Wertheimer, the so-called founding mothers of NPR, and more. Let's hear some of that now in conversation. The full book title is Dinners With Ruth: A Memoir on the Power of Friendships. Nina, it's always great when you come on the show. Welcome back to WNYC.

Nina Totenberg: Thank you, Bryan. I just want to say you really need to go back to work in the office, then I could see you in the flesh. I'm in New York because the book is published this week, and I really hoped I would meet you but it turns out you're still in your cave. [laughs]

Brian Lehrer: Maybe I will see you soon. Listeners, if you always wanted to ask Nina Totenberg a question but never had her over for dinner, now's your chance, thanks for the magic of a call-in show 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692 or you can tweet your question @BrianLehrer. Can I start with some, Nina Totenberg, prehistory, since this is a memoir, and everybody loves you?

Nina Totenberg: Yes.

Brian Lehrer: Where'd you grow up and what made you want to go into journalism in the first place?

Nina Totenberg: I grew up first in New York City, then the suburbs of New York City, then a little jaunt to Illinois to where my dad was a professor for a year in order to-- he figured, he had to pay for three daughter's college tuitions and better start being paid for teaching more. He started it with a friend at the University of Illinois and then became chairman of the string department at DU because he was a famous virtuoso violinist.

Then we moved to Boston, and eventually, I grew up there, I even got jobs there. I worked for the late Record American, which is now called the Boston Herald or the Boston Herald American. If you look, a little subtitle, I think is there, and eventually went to Washington to seek not fame and fortune, to seek a job covering the government of the United States.

Brian Lehrer: If your first contact with Ruth Bader Ginsburg was four years before you joined NPR, that'll be 1971. Where were you working or what were the circumstances of that contact?

Nina Totenberg: At the time, I was working for the Late Great National Observer, which was a weekly published by Dow Jones then, at that time, the owner of The Wall Street Journal. I was assigned, among other things, to cover the Supreme Court. I was reading this brief about sex discrimination, and it would turn out to be Justice Ginsburg's first brief filed in the Supreme Court.

It marked the first time that the Supreme Court held that women are covered by the Constitution's guarantee to equal protection of the law, but I didn't understand that. I really didn't understand that because women didn't have a vote at the time the 14th Amendment was passed. At that point in the press room at the Supreme Court, there were these little bitty phone booths, and I went in, and I dialed the number on the front of the brief at Rutgers University Law School.

Justice Ginsburg, then Ruth Ginsburg, answered the phone and she spent the next hour with me, teaching me her argument and with me asking questions and her answering. It was an incredible experience, and it marked the beginning of first a professional friendship, and ultimately a personal friendship as well.

Brian Lehrer: It's a wonderful story. Has that been firmly established in the law by now via the Supreme Court that the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment, which was opposed slavery amendment, of course, does also apply to women? I certainly still hear from callers sometimes who say we need an Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution for real gender equality. Do you understand the argument there, if the equal protection clause from the 14th already applies?

Nina Totenberg: It's an interesting question. The Supreme Court never fully embraced her argument that women are covered at the same high threshold as is the case with race, for example, because after all, the 14th amendment was adopted to protect racial minorities. The court has used a slightly lesser standard for women. It's not we're not a suspect class, we're an intermediate-level class, so there might be some reasons that you could discriminate against women.

Therefore the argument is made, and Justice Ginsburg certainly made it that you need another amendment of the constitution to make clear that women are a suspect class. That if they're treated differently, the presumption absolutely is that the law, the regulation, whatever, is unconstitutional. As you well know, the ERA came close to passing some decades ago, but it was not adopted by three-quarters of the states as required.

There is a movement now to try to get it to rejuvenate that old amendment, but I think it's really doomed. Even Ruth thought that you couldn't breathe new life into the old amendments, that you had to have a new amendment that went through the process again, and there certainly, I suspect would not be three-quarters of the states that would approve.

Brian Lehrer: Did Ginsburg think abortion rights should have been decided by the Supreme Court on a basis, something like that that it would violate equal protection, or that it would be sex discrimination, and in some way, to outlaw abortion, or something other than privacy?

Nina Totenberg: Yes. She actually had a case that went to the Supreme Court the same year as Roe, and the Supreme Court agreed to hear it, but this [unintelligible 00:08:05] requires a bit of a setup. It was a classic, what I call Ruthie in case. She had a woman who did not want to have an abortion, who was a captain in the Air Force. Under the regulations at the time, if you were a woman in the military service and you got pregnant, you either had to have an abortion, and they were usually performed on bases in foreign countries, or you were discharged.

Susan Struck did not want to have an abortion, she had made arrangements for some people she knew to adopt the child. Ruth took the case, all the way to the Supreme Court arguing as the flip side of what we argue about today, but the same principle. It's a really good way to understand her approach. The principle was personal autonomy over your own body and your future and your economic well-being, in her view.

She took this case, and if you have the right to not have an abortion, then you would also have the right to have an abortion. The Supreme Court agreed to hear that case. However, the government at the last minute realizing it likely would lose, caved and changed the regulation. There was really no more case, and the Supreme Court did not hear the case or decide it, and Roe became the only basis for abortion rights as we know them today.

Brian Lehrer: Was Robert Bork involved with that? He was the Solicitor General under Nixon, and I think it was at that time, this case that you're describing regarding choice in the other direction

but the government caved in if that was a Bork decision not to fight that?

Nina Totenberg: I don't think so but I could be wrong. I think he had already left by the time this happened, which would've been '73. I think he was maybe not. You may be right. You've asked me a question. I don't know the answer to it.

Brian Lehrer: That would be an interesting footnote to history, considering everything else about him. I see that the--

Nina Totenberg: It's entirely possible.

Brian Lehrer: I see in the book that the first Supreme court justice you invited for dinner was Justice Lewis Powell and his wife. Powell was appointed by Nixon in '72 but then voted for abortion rights in Roe v. Wade, which did of course come the very next year, 1973, as you just cited. Do you remember asking Powell anything like how hard it was to go against the conservative president who appointed him?

Nina Totenberg: I don't think he or almost any justice thinks it's difficult if they're correct. If their view of the law is correct to rule against the president who appointed him or now her. I've never met a Supreme court justice who personally thinks that's difficult, but it is true that the justices on the Supreme court today more closely align with the presidents who appointed them than in previous times.

There is no center left, that center remaining on the court. I've been covering the court for many, many decades, really since 1968. I've never known a court without a center until now. I don't know of a court without a center, actually going back nearly 100 years.

Brian Lehrer: My guest is NPR legal affairs correspondent, Nina Totenberg. Her new book is Dinners with Ruth: A Memoir on the Power of Friendships. I will mention by the way, and I'll say it again at the end of the segment, that Nina will be doing a live appearance here in New York, tonight, 6:30 for both in-person and live streaming from the Streicker Center at Temple Emanu-El 5th avenue and 65th street in Manhattan.

Nina in conversation with Preet Bharara, 6:30 tonight at Temple Emanu-El Streicker Center. Let's take a phone call. This, I guess it won't surprise you, is a question that a number of callers on our board have for you about some of the stories in this book and some of the premise. Michael in Manhattan, you're on WNYC. You get to represent those callers.

Michael: Hi. For many years I turned into NPR and if there was something crazy going on with the Supreme court, I would think, "Nina Totenberg's going to explain it to me. It's going to be fine," but then later, it was only years later when it became out that you and Justice Ginsburg were such good friends, made me wonder, did you ever feel that you should recuse yourself from reporting on either the court or specifically if there was something that Justice Ginsburg was specifically involved with [unintelligible 00:13:16] I'm such close friends with this person, there's some journalistic ethic where I should not be the person reporting on this.

Nina Totenberg: Washington is a small town. If reporters recuse themselves because they knew somebody or had known them for a very long time and remain friends with them, and they did it fairly, that is in the sense that everybody recused themselves on the same basis, I don't think you'd have any reporters left in Washington. If you have been there a long time, you have friends and associations and part of the job is to put your friendship aside when necessary.

I was great friends with Justice Antonin Scalia, who was the court's most conservative member for a very long time until his death in 2016. It never seriously occurred to me to recuse myself. There are times when it's uncomfortable. When Justice Ginsburg made inappropriate remarks about, then-candidate Trump, she had to eat her words. We had a long-scheduled interview that week and she asked me not to ask her about it. I just said, "Ruth, I can't do that. That's my job. You can ring me out if you want." I did and she did ring me out.

I remember that when there was some controversy about Justice Scalia participating in a question involving then Vice President Cheney. He didn't recuse himself and he'd gone duck hunting with Cheney. There was something of a brouhaha about it. He didn't say anything for the longest of times and I wrote about it. It was very interesting to write about it because I had to learn some history. Supreme court justices are generally not intimates of presidents anymore, but not that long ago they were.

They played poker at the White House with the president and in the Reagan administration, not with President Reagan, but with his close associates. Certainly in the '50s, there were justices who played poker at the White House and they still ruled against the president. A very famous case in the '40s involving President Truman's basically nationalization for all practical purposes during the Korean War, involving ending a strike, I think it was involving a steel company. The court ruled said he couldn't do that.

It didn't ruin Truman's relationship with his friends on the court. A reporter doesn't have a real stake in any of these cases. I think the only time I recused myself was having not to do with a person, but a subject. On my honeymoon, I'd been run over by a motorboat and nearly died. There was a case involving federal law that required motorboats to have more protections for accidents exactly like this.

I went to my boss and I said, "I should not be covering this argument but I will," and I didn't, but what I did do, I did cover the decision because covering the decision is covering the decision. I didn't have a dog in the fight anymore. The court had decided the issue and I was explaining it. If I had ever felt that way about Ruth, I would've recused myself but there was no occasion to do that.

Brian Lehrer: You do say I believe that you wouldn't have invited members of Congress to dinner, but you considered Supreme court justice as different. Is that right?

Nina Totenberg: To some extent that's right. It was right at the time when I was very young and I really didn't know members of Congress that I could have invited to dinner with their wives, but I do now know some members of Congress who have been around a very long time. I would and have had dinner with Alan Simpson, even though we had a famous fight at one point during the Thomas nomination.

My husband and I have known Pat Leahy for decades. My husband knew him well before I did. They come to dinner occasionally but by and large politicians are different because there are no rules. In the case of the Supreme court, there are rules. It's as if they were on a top-secret intelligence committee.

Brian Lehrer: Always.

Nina Totenberg: They are not ever supposed to discuss pending cases. You can ask them about stuff afterwards. If they're still on the court, they probably won't answer you but after there when they're off the court, sometimes they do talk about what their thoughts were about it and why they wrote it the way they did, but not while the case is pending. It's really clear.

Brian Lehrer: Nina Totenberg with us, with her new memoir Dinners with Ruth. Alice in Islip, you're on WNYC with Nina. Hi Alice.

Alice: No, I'm in Ridgewood, but people might be interested to know that Nina can really sing. She sang at my mother's wedding. Her second wedding [crosstalk]

Nina Totenberg: Who's your mother?

Alice: Amanda Mckenzie Hobart but this is to how small the Washington community is. My father actually had Nina's beat before she did at the Washington Post.

Brian Lehrer: Wow.

Nina Totenberg: It's true. He did. He did.

Brian Lehrer: There we go.

Nina Totenberg: I learned many things from Jack McKenzie. He was a wonderful, wonderful reporter and a thoughtful gentle human being. It does go to where the small town Washington is. [crosstalk] After I was married, my first husband was the United States Senator.

Brian Lehrer: Which you wrote about in the book. Alice, did you have a question for Nina about music?

Alice: Yes. She can really sing. I thought she could tell us about that. Also, I

just wanted to mention that my father Jack is [unintelligible 00:20:03] too. He often calls into your show, so you probably [unintelligible 00:20:09] all the time anyway. I'd love to hear Nina talk about her private singing career.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you. Didn't you go to the opera with Ginsburg in addition to going to dinner?

Nina Totenberg: I went to the opera with her occasionally and I always saw her at the opera. We usually were at openings of operas and there would be a little party afterward, and there was always a table reserved for her. She always told me and my husband David Reines to come over and sit with her because I think she was most comfortable with us. We always had a lovely time at the opera together.

I come from a musical family. As I said, my father was a great virtuoso concert violinist and there's a chapter in the book about his [unintelligible 00:21:06] being stolen and recovered 35 years later. It's a great tale. I titled the chapter, my father's friend, something about my father's friends because this is a book about friendships and it's about really it's about friendships, particularly of women of my era who came to the workplace when there were almost none of us there.

We weren't trying to break a glass ceiling. We were trying to get a foot in the door and Cokie, and Linda were part of that. NPR was certainly part of that because we were mainly women at NPR because no men would take the job for the money they were paying at the time. It is a book about friendships and my women's friendships, but also my men friendships. It's the way I framed the memoir because it was the only way that made any sense to me.

Brian Lehrer: Some of the things about you and Ruth bonding over sexism in your different professions, you and Ruth became closer as you tell it around medical issues in your lives and your family's lives, especially your husband's lives. Interestingly, at one point she advises you not just on how to deal with the emotional toll of your husband at the time's illness, but advise you to not lose your career to it. It's such a perennial issue for women, obviously who tend to be the caregivers in the families and to make those professional sacrifices. Can you tell the story of how that came up and how it affected you?

Nina Totenberg: Yes. You have to remember Ruth's husband had testicular cancer when they were in law school and survived, but it was a very difficult time. It's the base-- it's the basis for the movie On the Basis of Sex. Because it that's a biographical movie about her. I think you call it a biopic or a biopic. I never know how to say it. Anyway, my husband, Floyd Haskell had it fell on our front path as he was going to arrange my 50th birthday party at a restaurant.

It was in the middle of an ice storm and he had a very serious brain injury, head injury and partially a brain injury as well. I mean, his brain expanded enormously. He had surgeries, he was in the hospital from months on end in the ICU, and then eventually transferred to a rehab hospital and then came home.

But when he was in the hospital and in the beginning, I was sort of there all the time. Ruth said to me, one day she said, "Nina, you need to go to the hospital for an hour a day, and make sure everything is being done correctly for Floyd. But you need to go back to work so that you don't lose yourself because it may not be the best work you've ever done, but it'll still be good work.

You need to be there as you are as a whole human being for him when he comes home." It was the best advice anybody gave me. I did it and it worked. I just barely held on, but I held on. He did come home. He lived another four years until he died and it was wonderful advice that I often pass on to other people.

Brian Lehrer: On a lighter note, the press release free book among the highlights it singles out, mentioned you and Ginsburg discussing clothing as armor for women in the male-dominated professional world. What was one of those conversations about?

Nina Totenberg: Well, we didn't discuss it as armor, I think, but it was an understood thing. Why would two professional women in our 30s and then later 40, 50, 60, 70s go shopping when we had a minute at a judicial conference, for example, together? The answer was pretty clear. In that period of time, women in the workforce dressed like nuns. They all wore-- they would look as much like a man actually, as they could. They all wore dark suits, a white shirt, black pants, and Pearl earrings. That was it.

They didn't want to stand out, and we wanted to stand out. We wanted people to understand we're here, we're different. We like being different and we are just as capable. That was I think-- I understood it instantly about her and she understood it instantly about me.

Brian Lehrer: Andrea in Brooklyn. You're on WNYC with Nita Totenberg. Hi, Andrea.

Andrea: Good morning. It's Andrea, but never mind.

Brian Lehrer: Oh, sorry.

Andrea: Thank you very much to both you I'm commonly assumed to be a woman. Mr. Lehrer and Ms. Totenberg thank you very much for the wonderful work you both do. I'm pretty much attached to the radio. The answer to my question, my well-being, the book, and I look forward to reading it, but for me is the elephant in the room. Did the subject of Justice Ginsburg's retirement pop up during one of those dinners?

Nina Totenberg: No. Ruth was--

Andrea: I'm sorry [unintelligible 00:26:50]

Brian Lehrer: Go, go ahead. Nina.

Nina Totenberg: I would say that anything that Ruth wanted me to know other than the most subtle things about life, like that advice that she gave me, she said in public, and she said in public that she did not-- was not considering retiring. She gave different explanations. Some of them amusing and others, not so much. I think that ultimately I understood that when she didn't retire, as I later learned, she never told me that she had lunch with Obama in 2013.

That he suggested to her that this might be the time to retire. She was at the top of her game then. She was not frail. She was not sick. She was not old in any sense of the word. She was, I guess, 79 or something like that. She maybe even 78, she might have been the age I am today and I'm not retiring.

She also knew-- remember there was a filibuster at the time. I think she believed that there would nobody really good could be confirmed, but mostly I think in part she wanted, she really expected that Hillary Clinton would be president in 2016. She thought that she wanted to give her the first woman president the chance to fill the seat. But she never said that to me. That's my inference.

Brian Lehrer: Let me ask you about one unrelated legal affairs thing in the news right now. It's a little speculative. I'm just curious on all these Trump cases and investigations. Are there one or two aspects you think are most likely to wind up in the lap of the Supreme Court?

Nina Totenberg: I can't tell yet. I really can't tell yet because we don't know if the justice department's investigation is going to bear enough fruit that there would be an indictment against the president. We don't know how these-- even the fight about the documents at Mar-a-Lago are going to shake out.

I think that may get to the Supreme court the most quickly if anything does, but I really, I don't have an informed view of any of this yet, because you can't tell which cases are going to get on the rocket docket to the Supreme court and which ones are just going to molder around for a while.

Brian Lehrer: Nina Totenberg, NPR's legal affairs correspondent. Her brand new book is Dinners with Ruth: A Memoir on the Power of Friendships. Nina will be doing a live appearance here in New York, tonight at 6:30 for both in-person and live streaming from the Streicker Center at Temple Emanu-El 5th Avenue in 65th Street in Manhattan, Nina in conversation with Preet Bharara there.

That ought to be a great one for legal geeking out on legal affairs. Nina and Preet, 6:30 tonight, Temple Emmanu-El, Streicker Center in person or live stream, and Nina, some wonderful book. Thank you for sharing so much of yourself for your many admirers in it. Thanks for sharing so much of it with us.

Nina Totenberg: Thank you for having me, Brian. You take care.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.