Morning Edition

Morning Edition

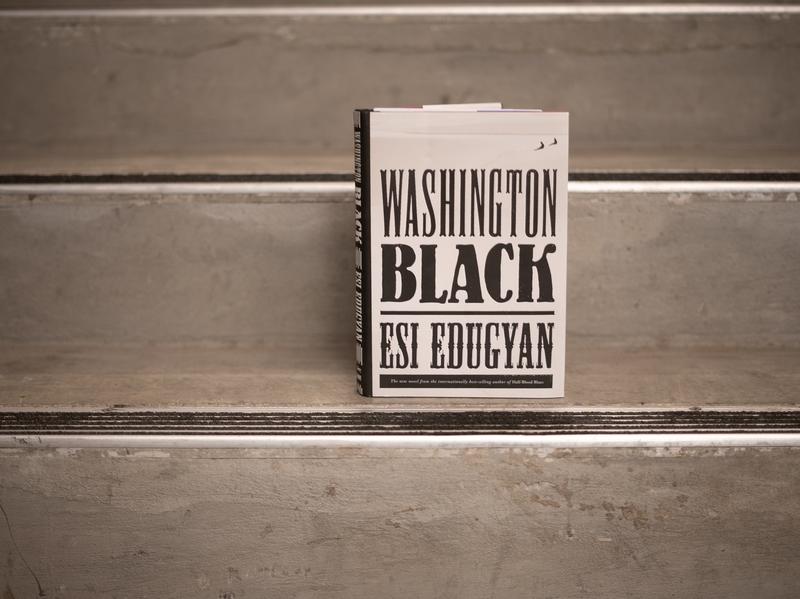

Novelist Esi Edugyan On Black Genius And What Comes After Slavery

At the beginning of Esi Edugyan's new book Washington Black, it seems the narrator is not going anywhere.

It's the 1830s, and the narrator, a boy named George Washington Black, is enslaved on the British-controlled island of Barbados. He seems likely to be worked to death in sugar cane fields — until he's carried away.

He's made into an assistant of a visiting white man, and they become friends. Sort of.

"Any true friendship between them is impossible because of the power imbalance – it's just too great," Edugyan says in an interview.

Yet the white Englishman takes Washington away with him and even teaches "Wash" to read. Soon, the boy is soon revealed to be an almost preternaturally talented illustrator, drawing plants and birds and soaking up knowledge he'd been denied as a slave.

Even the novelist, a black Canadian, says she didn't really plan for the story to turn out that way.

"You know, you're starting a novel, you're really playing with character, and you're letting them interact, and you're seeing what comes of it," Edugyan says. "And at least for me, as a writer, I really have no idea where my story is going at the outset of it."

Washington Black has been shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize. Edugyan spoke to us before the final award announcement.

Interview Highlights

On the hidden talents of Washington Black

Part of what I was wanting to explore was this idea of, I guess, black genius as being something that obviously would have existed back then — that you would have people with great gifts — but that this is something that would have been snuffed out, very brutally and without much thought. A friend of mine said that we tend to think of slavery in terms of the loss of black bodies, but we don't really stop so much to think about the loss of potential of black greatness, of black genius.

On moving past slavery in the plot of the novel

What I really wanted to explore was his life post-slavery. And to show how by being physically free, we think of that as being the end of slavery — well, he's not in chains, he's gotten away, he's physically free. But I really think that there had to be huge psychological ramifications to having been a slave — even while you're free in body, that obviously you're carrying with you a great trauma, and probably a great sense of bewilderment about your place in the world. And I really wanted to express that. ...

I think the main thing that [Washington] resents is the feeling that the man who freed him did not respect him as an equal. And this is really the crux of what starts to eat at him, is that: This man made this great gesture of helping him be free, and yet [Washington] really has the sense that though this man thought of himself as an abolitionist and a great crusader for good in the world, that he didn't really recognize the humanity of Washington.

On the relevance of the story in 2018

I think we're still dealing with, obviously, a lot of the themes and concerns that come up in the book — things like racial justice, racial inequality, the idea that some lives are more worthy than other lives — but also this idea of people being galvanized to do something in the world. If you think of the abolitionists and how they — they really had to not only change their own thinking about slavery, which would have been just a very quotidian, everyday thing. I mean, the sugar arrived at your table in the mornings, you put it in your oatmeal; you understood that this was the product of slave labor but it was going on in a part of the world that you would probably never in your life see, done by people who you had really nothing in common with. So to change their own thinking about that, and then to galvanize a whole society to change public thinking: That this is something huge and amazing.

On the charge that the history in the book is "old news," in light of the current status of black North Americans

To me that's — it's quite shocking, because I mean, how can one watch, say, videos of police officers gunning down unarmed citizens? How could anybody watch those videos and still contend that there is not a problem and that we have racial equality and fairness? This is baffling to me.

I feel that there has been regression, that there's been steps backwards in terms of people wanting to understand each other's experience and really being open to it. I think one of the things that novels can do is to bring a reader into a character's experience — especially a character who is nothing like them. We're dealing here with a boy in 1830s Barbados who's a slave. But if you can read that, and start to see maybe how you're like him, similarities — and also to feel for him, as he's going through these hardships — if you can do that, perhaps that can be the beginnings of some kind of empathy.

Kelli Wessinger and Reena Advani produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Patrick Jarenwattananon adapted it for the Web.

9(MDEwODYxNTQyMDEzNjAxODk2Nzc2NzNmYQ001))