New York City considers its lead poisoning prevention program one of the best in the country. City officials often tout the fact that since 2005, the number of children with high blood lead levels has declined by more than 70 percent.

But that statistic doesn’t capture the full picture of lead exposure in NYC. Public health experts argue the city's health department uses an outdated standard to measure high lead levels - causing thousands of children to go uncounted in the city's tally of kids most at risk.

In New York City, the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene considers a child’s blood lead level to be high if it tests at or above 10 micrograms per deciliter. This standard was once shared by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, but after weighing a growing body of evidence suggesting that even low levels of lead can have a damaging effect on a child's development, the CDC adjusted its threshold to 5 micrograms per deciliter in 2012. While the agency can't require states and municipalities to follow suit, it does recommend they do so.

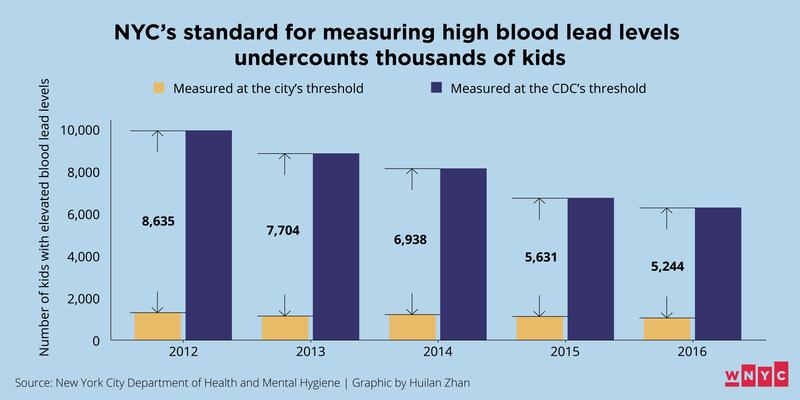

New York City, however, has maintained its standard at 10 micrograms. In 2016, city officials reported that only about 1,000 children tested above that level. But if the health department were to follow CDC guidelines, it would have added an additional 5,000 children to its list, according to data acquired by WNYC through a freedom of information request.

Current research shows that no level of lead exposure is safe for children, and significant cognitive damage occurs at low blood lead levels. A 2000 study by researchers at the Children's Hospital Medical Center in Cincinnati estimated that, as blood lead levels increase from 1 to 10 micrograms per deciliter, children’s IQ can drop anywhere from 3.9 to 7.4 points. Other consequences of lead exposure include slowed growth and development, decreased attention span and behavioral issues.

When children test at 5 micrograms per deciliter, the CDC recommends public health officials conduct home inspections to determine the source of lead contamination and eliminate it. “There’s likely more lead in their environment than other places,” said Sharunda Buchanan, a director in the CDC’s National Center for Environmental Health. “They’re probably the most at risk kids.”

Contrary to that advice, New York City's health code only requires an environmental inspection be conducted when a child's blood lead level tests at 15 micrograms per deciliter or greater, although the health department does offer the option of a home visit in cases where younger children test at lower levels. For children under 16 months, that standard is set at 8 micrograms or above.

During such visits, health officials inspect a child’s home for lead paint, interview parents about other potential sources of exposure, such as pottery and imported spices, and run lead tests, if deemed necessary. Lead paint is the leading cause of lead exposure in New York City.

For most children who fall between the city's standard and the CDC's, the department of health sends home a letter to families and their medical providers, alerting them to the risks of lead exposure and tips on prevention, including a reminder that they can call 311 to ensure any chipping paint in their apartment is fixed. It also recommends children be retested after a few months to make sure their lead levels decline.

Corinne Schiff, deputy commissioner of environmental health, said visiting the home of every child who tested at or above the CDC's standard would require the city to vastly expand the resources of its lead-prevention program.

“The standards that are set in New York City law are the levels at which New York City is required to do a home intervention,” said Schiff. “We’ve been working over the years to do more and more intervention, particularly with young children who are the children most at risk, at lower and lower blood lead levels.”

New York City is not alone in departing from federal guidelines. Other cities and states have also kept their threshold at 10 micrograms per deciliter. And even those that have aligned their standards since 2012 - including California, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Washington and Oregon - don’t always do more to address the issue when a child tests above 5 micrograms.

Many agencies only send educational letters or call the family. Some conduct home visits if families request one, but most don’t have the resources to carry out regular home inspections for children with lead levels below 10, leaving them in a similar situation as New York City.

Some public health experts are concerned a lack of intervention at a national level could cause long-term harm, not just to children, but to society as a whole.

David Rosner, professor at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, said generations of children with low-level exposures will suffer from “subtle but important neurological deficits,” like decreased IQ, lower academic achievement, a lack of impulse control and even delinquent behavior, which was noted in a study released last month by researchers at Harvard.

“We’ll continue to act as if it’s the kid’s problems and we’ll address it by blaming the children,” Rosner said, “rather than understanding that we as a society have created the conditions that are poisoning these children.”

Other experts worry that even a reference level of 5 is too high. “That’s almost an antiquated way of thinking about childhood lead exposure,” said Dr. Leonardo Trasande, a pediatrician and associate professor at New York University School of Medicine. “Every level of lead from above zero is potentially unsafe for the developing brain.”

The CDC is currently considering lowering the reference level further, and expects to make a decision in the coming months, Buchanan said.