All Things Considered

All Things Considered

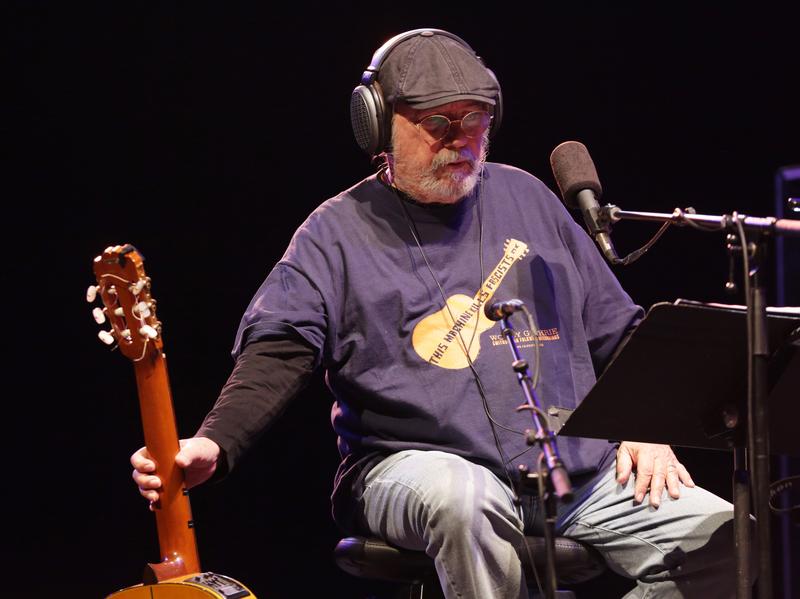

On 'Para La Espera,' Silvio Rodríguez Combines The Personal And Political

You could say Silvio Rodríguez became the artist he is today at age 12, when his home country's dictatorship was overthrown in the Cuban Revolution. Over the years, Rodríguez's unwavering support of the revolution drew intense criticism from the Cuban exile community, but social activism has always been part of his songs. Generations across Latin America have been inspired by the poetry and politics of the Cuban musician's lyrics.

Now, Rodríguez has released an album that's both personal and political. It's called Para la espera -- "For the Wait."

For the past 10 years, Rodríguez has been performing free concerts in some of the poorest neighborhoods of Cuba. He calls it the Endless Tour.

"That spirit of sharing culture comes from my generation of troubadours. We used to go sing everywhere: factories, schools, barrios and prisons," Rodríguez says. "The Endless Tour started when a policeman knocked on my door inviting me to the barrio he cared for, called 'The Necktie.' We continued doing it and we've done 108 concerts."

Rodríguez's generation came together in 1967 and formed a movement called La Nueva Trova Cubana, or The New Cuban Troubadours. Songs like "Ojalá" dealt with all of the aspects of being in a relationship: love and pain, joy and sadness. "La Maza" is a declaration of principles for being an artist. To Rodríguez, the songs are self-explanatory: "Many times they're sudden feelings that create songs — words just come to me in a moment. And that's why it's hard to explain them."

A legend like Rodríguez is a hard act to follow. Fifty-year-old Kelvis Ochoa comes from the generation after the Cuban singer.

"He's one of the great Latin American poets," Ochoa says. "He's written so many songs, many of them are so good. It's overwhelming, it's way beyond our reach."

Singer and composer David Byrne is another Rodríguez fan, and refers to the artist's lyrics as impressionist, abstract and political. In the early 1990s, the Talking Heads frontman licensed Cuban music with his partner and released it on their Luaka Bop label. The releases included an album of Rodríguez's greatest hits, a collection of 12 Byrne-selected songs that became their biggest seller.

"What really shocked me was that Silvio, despite being as popular as he is in Latin America, had never had a greatest hits record," Byrne says. "Maybe he thought this was a kind of crass thing, and he thought the kind of commercial thing that only North Americans would do, but he'd never done it. But he agreed to do it with us. I think he might have been thinking that, and rightly, that we were going to introduce him to an audience that otherwise may not have heard his music, and there's some truth to that."

Over the past 50 years, Rodríguez has recorded 24 albums. Before pandemic-related shutdowns, he was working on a new one with a large group of musicians. After seeing what others were doing, he decided to bring back the troubadour and resume production.

"I started seeing messages, songs, even concerts on the internet, so I thought about taking some of the songs I've already composed — which were not in the other record I was working on — and I began to organize the material and offer it to people, as a way to help them cope during the pandemic."

His efforts resulted in Para la espera. The meaning of the album's title is twofold: Rodríguez says it alludes to the uncertainty of the pandemic and to the nearly two-decade wait for the release of the Cuban Five, intelligence officers arrested in the U.S. who become national heroes.

Rodríguez's music has now been part of the soundtrack of life in Cuba, and throughout Latin America, for more than 50 years. But the musician says he's always trying to look forward.

"I'm a man of hope. I'm a man who believes in the future, above all because I'm from this country and because we have this people," he says. "We're not perfect, but we're combative and hopeful. I'm part of all of this."

LaTesha Harris adapted this story for the Web.

9(MDEwODYxNTQyMDEzNjAxODk2Nzc2NzNmYQ001))