SchoolBook

SchoolBook

Public Advocate Sues New York City over Glitches in Special Ed Tracking

Public Advocate Letitia James filed a lawsuit on Monday that alleged the city's computer system for tracking students with disabilities was such a failure that it led to the loss not only of basic services for children in need but also of potentially hundreds of millions of dollars in federal Medicaid reimbursements.

The city began developing the Special Education Student Information System (SESIS) in 2008. It was supposed to track whether students with disabilities received whatever services were spelled out on their individualized education programs. This type of reporting is required by state and federal laws.

But James said the system was so badly built it couldn't comply.

"The failure of the system has been one of the department's worst-kept secrets," she said, describing a system that frequently crashed and was so unwieldy that teachers had trouble putting information in about their students. The teachers union even won back wages because its members had to work longer hours just to deal with SESIS.

These problems were cited in a 2013 audit by the city comptroller. In 2011, the city missed a deadline for placing 2,500 kindergarteners with special needs into appropriate schools. And James said both her office and the Independent Budget Office had trouble getting data on students from SESIS when they asked for it.

The public advocate claimed these problems with documentation contributed to the city's failure to recoup $356 million in federal Medicaid dollars for eligible special-education services between the 2012 and 2014 fiscal years. City Comptroller Scott Stringer arrived at that dollar figure with his own report in 2014.

The lawsuit asked a state court to conduct a formal inquiry and force the city to fix the problems. A city law department spokesman said the agency would review the suit once it's served.

The Department of Education did not comment on the suit but pointed to a 10 percent increase in graduation rates for students with disabilities since 2012, and efforts to hire 300 more occupational therapists.

It said it's also provided more training to school staff around the data systems.

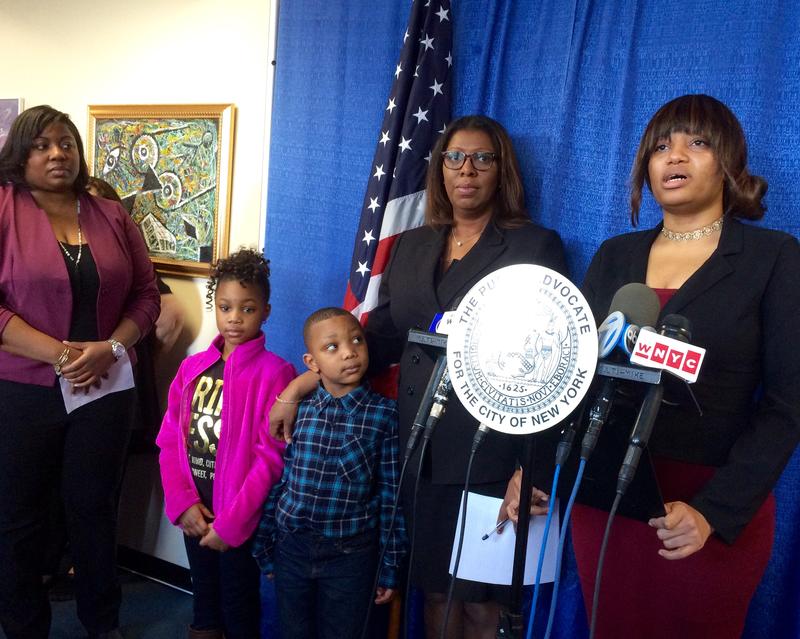

James wasn't impressed by the city's recent efforts. Standing with her at the press conference was Modisha Moses, whose six-year-old son is nonverbal and has autism. She said his school delayed occupational therapy at the beginning of the school year for grinding his teeth and other sensory issues.

She said she heard excuses from school and district officials that they didn't have the staff to input his data into the computer system.

"My son should not be on a waiting list for something he is mandated to receive," Moses said.