If you’ve never heard of Carmen Herrera, a Cuban-born, New York painter who happens to be 101-years-old, you can be forgiven. Virtually no one has seen her work in depth. She did not sell her first painting until she was almost 90, and there is a certain temptation to sentimentalize her as an old-lady painter. But don’t confuse her with famous late-bloomers like Grandma Moses, who is known for her nostalgic scenes of farm life. Herrera, by contrast, got off to a precocious start and favors hard-edged abstraction, as all the world will soon know. “Carmen Herrera: Lines of Sight,” which opens today at the Whitney Museum, is a triumph of revisionist art history.

Born in Havana in 1915, Herrera immigrated to New York around 1954, in the years before Castro came to power. By no means a loner, she studied at the Art Students League and, together with her schoolteacher-husband, befriended some of the most advanced artists in the city, Barnett Newman included. But when she tried to interest art dealers in her work, Herrera had no luck. She was female and Latina, and so doubly suspect in an era enamored of Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings and macho Abstract Expressionism theatrics.

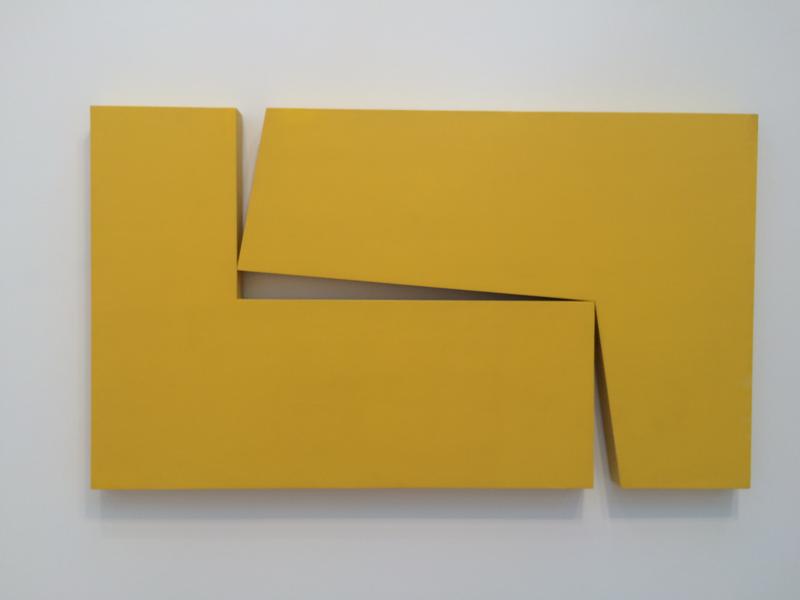

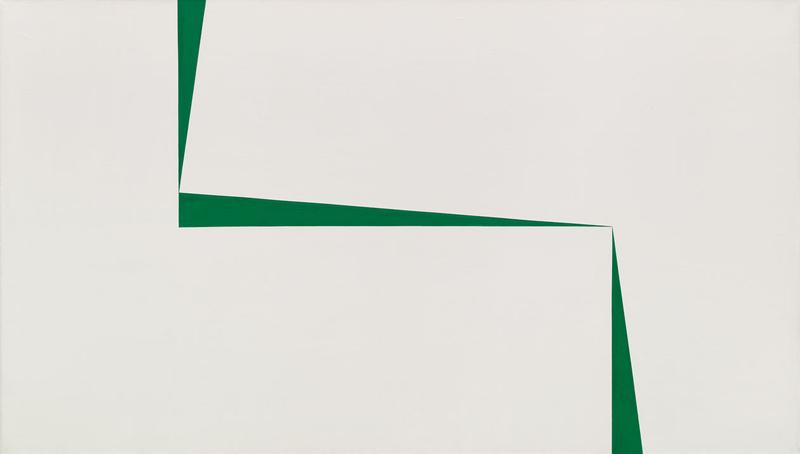

Despite the rejections, Herrera continued to paint and go her own way. Her work looks handsome-to-dazzling on the museum’s (skylighted) 8th floor. A central gallery that re-unites nine of her “Blanco y Verde” is the highpoint. The “Blanco y Verde” paintings create surprising drama out of elementary forms: namely, all-white grounds pierced by elongated green triangles. Some of the triangles are so thin they seem to be on the verge of disappearing; others are knife-sharp and slice tautly through space. In the end, I don’t think Herrera is as original as Ellsworth Kelly, who took his forms from nature and reduced them to slabs of pure color, but her work is never less than intelligent and eye-catching. It touchingly suggests that life is a puzzle in which none of the pieces quite fit.

* * *

A more playful challenge to the accepted story of art opened this week at the Jewish Museum. “Take Me (I’m Yours)” is an amusing, idea-permeated group show consisting of 42 sculptures and installations by as many artists – all of the pieces double as giveaways. The show violates every rule of museum etiquette by inviting you to not only touch the art, but to put it in your pocket and take it home with you. The presiding spirit here is Felix Gonzalez-Torres (another Cuban-American, coincidentally), whose mounds of individually-wrapped hard candies inaugurated the tradition of please-touch-the-art art around 1990. In addition to his bonbons, you can come away from the current show with all kinds of art swag: campaign-style buttons inscribed with cryptic messages, temporary tattoos, a Yoko Ono “air capsule,” a Miss America-style banner updated by Andrea Bowers to convey p.c. uplift (“Families Do Not Have Borders,” for instance). I took home, among other things, a small sculpture by Uri Aran, a life-size plaster cast of a takeout coffee lid. It looks a little diminished on my fireplace mantel, and most of the other stuff lost its allure once it got home, proving perhaps, that there’s nothing like an art museum setting to lend objects gravitas.