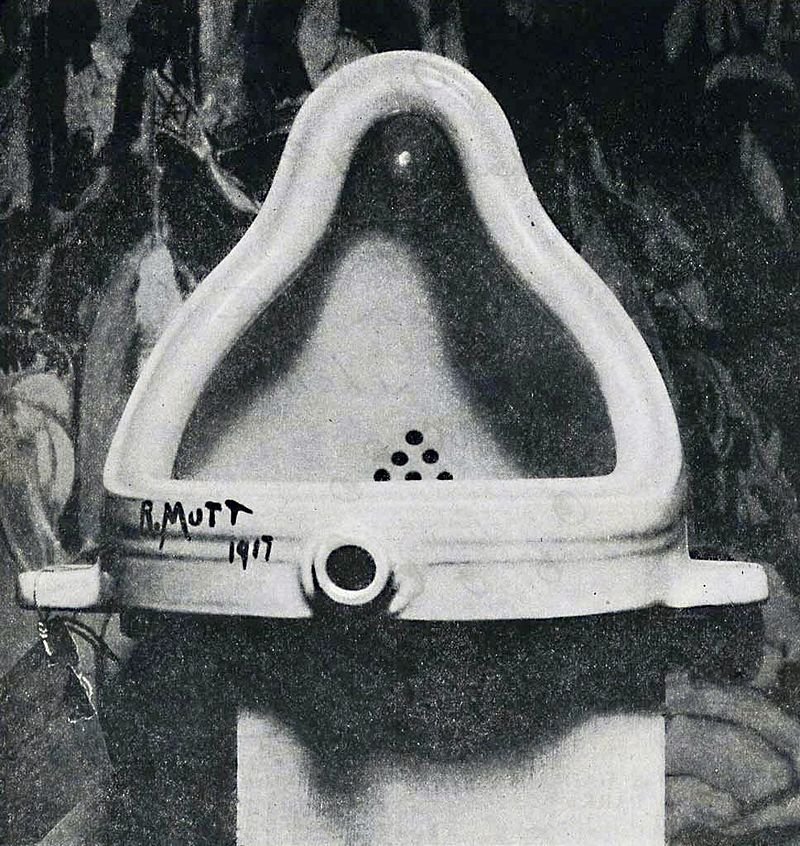

There are few modern works more celebrated than Marcel Duchamp’s “Fountain,” which elevated a store-bought porcelain urinal into the ethereal realm of art. This week marks the centennial of its unveiling in New York City – or rather, of its non-unveiling.

In April 1917, when Duchamp audaciously submitted the urinal to a group exhibition hosted by the Society of Independent Artists, the piece was deemed an indecent joke and flatly rejected. It eventually went missing.

Today, it survives only in the form of a dozen or so replicas, and of course by epic reputation. Universally regarded as a modern masterpiece, the “Fountain” answers an age-old question – “What is art?” – with brilliant concision: Art is whatever an artist chooses to exhibit.

To celebrate the “Fountain’s” centennial, Francis M. Naumann, the well-known Duchamp scholar and art dealer, has mounted a show at his gallery, at 20 West 57th Street. The exhibition, which remains up through May 26, brings together the work of some 30 contemporary artists who have adopted urinals as their subject, usually with undisguised affection.

Kathleen Gilje redoes the urinal as a sainted object, complete with a medieval halo and a gold-leaf ground. (“Sant’Orinale,” of 2017). Sherrie Levine similarly injects an aura of religiosity in her “Fountain (After Marcel Duchamp), Madonna,” of 1991, a gleaming bronze sculpture whose bulky triangular shape suggests the head and shoulders of a Madonna. It implicitly anoints Duchamp’s “Fountain” the mother of all appropriation art.

Mike Bidlo has also cast a urinal in bronze, and one riven by picturesque cracks. Jonathan Santlofer contributes a bas-relief inscribed with a portrait of Duchamp in profile, looking like a statesman out of the neo-classical past. The sweetness implicit in the show becomes overt in Sophie Matisse’s “Urinal Cake,” a meringue confection which bears the date 1998 but was baked freshly for the current show.

* * *

Duchamp’s influence was, of course, infinitely broader than the show suggests. His presence in contemporary art is so pervasive it’s like trying to explain the significance of air. So I thought visiting another absorbing show this week, Jane Benson’s “Song For Sebald,” at LMAK Gallery, at 298 Grand Street (up through May 7). The show takes its inspiration from a Duchamp-style readymade, in this case a published book – W.G. Sebald’s meandering novel, “Rings of Saturn,” from which Benson has cut out every word except for do, re and the other notes of the scale. In the process, the pages of a novel metamorphose into sheet music. You can put on headphones to hear the melodies. The work as a whole is sparely poetic and deeply meditative and offers a soothing refuge from the hubbub of the streets.