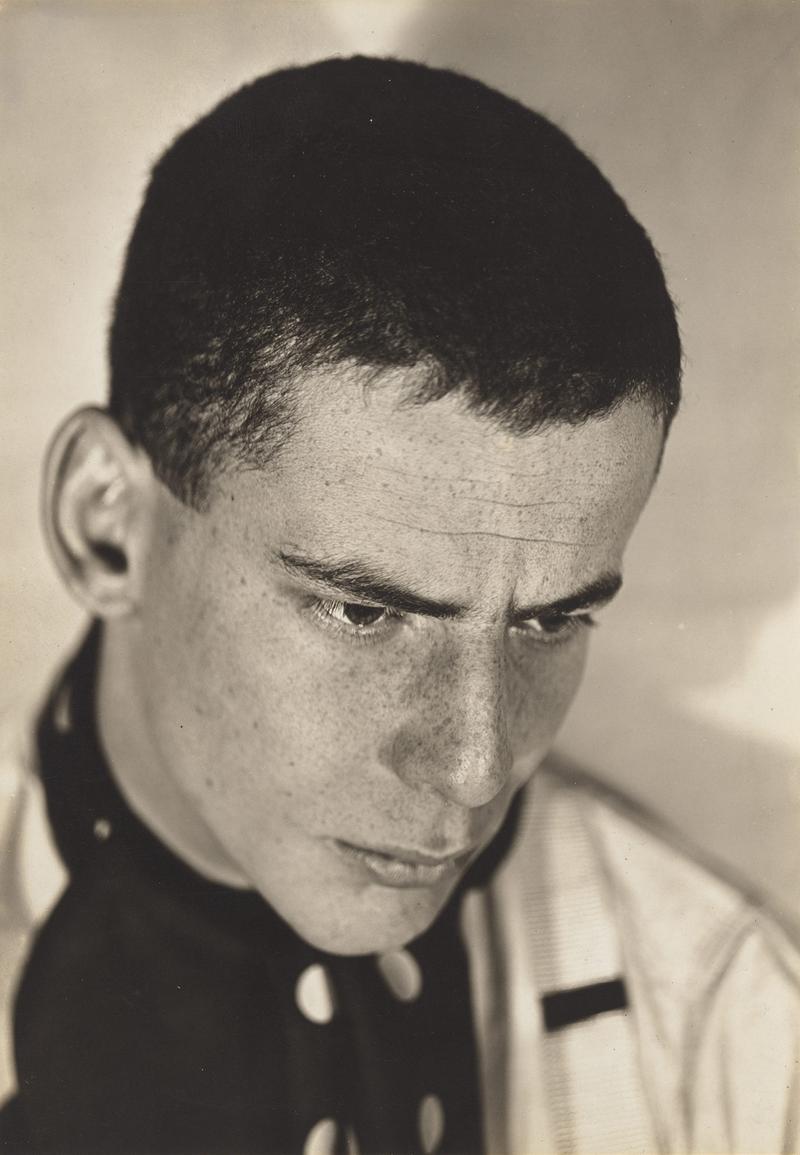

Lincoln Kirstein was half aristocrat, and half bohemian. Raised in Boston, an heir to the Filene’s department store fortune, he quickly made his way to New York and became essential to the life of the city’s cultural institutions. Today, he is best-known as the passionate impresario who co-founded of the New York City Ballet, in 1948, after convincing the Russian choreographer George Balanchine to move to New York and lend him a hand.

Kirstein was equally enamored of the visual arts, and “Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern,” which is now at the Museum of Modern Art, is a fascinating look at his sometimes questionable art infatuations. Deftly organized by Jodi Hauptman and Samantha Friedman, the show reminds us that Kirstein’s influence on the museum was in some ways unlikely. For one thing, he never joined the staff of MoMA. For another, his taste was problematic. Conservative in his artistic outlook, he favored figuration in the age of abstraction. He had no patience for the improvisatory styles of the ‘50s, and spoke of the Abstract Expressionists as “ostentatious” and “self-pitying.”

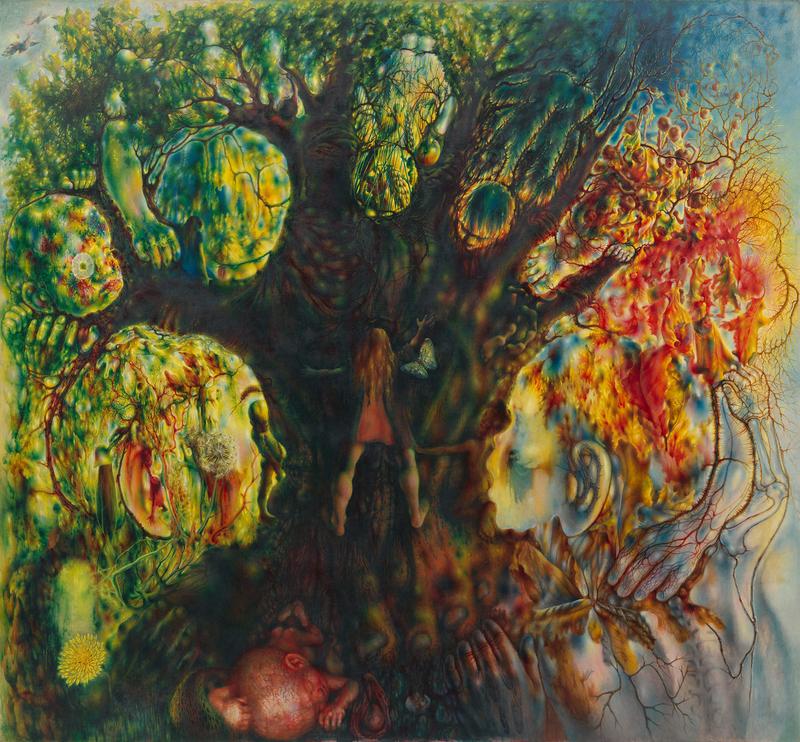

He preferred artists who showed off their technical skill, artists who could draw a hand with perfect anatomical correctness. Tellingly, he helped the museum acquire Pavel Tchelitchew’s “Hide and Seek,” that massive, witchy picture in which infants’ heads rendered in radioactive colors nestle creepily in tree branches. I remember admiring it as a child, when it was one of the main attractions at MoMA, but today it strikes me as painful (can we please not play games with infants?). I don’t know that this show will help to revive Tchelitchew’s reputation.

But it will help revive Kirstein’s reputation – and he deserves the tribute. In 1939, ten years after the museum’s founding, he generously gave MoMA his personal archive of 5,000 ballet-related books, drawings and ephemera. The best work in the current show, I think, pertains to his archive and occupies a large gallery where you can watch film clips of early dances and study related drawings. I especially enjoyed the drawings for the ballets “Filling Station” (by Paul Cadmus) and “Billy the Kid” (by Jared French). Kirstein also did an ever-lasting favor for the museum when he shored up its holdings of photographs by Walker Evans and sculpture by Elie Nadelman, two of his best pet artists.

All in all, Kirstein was an impressive personality – he was handsome, well-educated, energetic and patriotic (he served as one of the so-called Monuments Men at the end of World War II, retrieving art from the Nazis). His personal life was nothing if not inventive. A self-described outsider who was Jewish and bisexual, he fell in love with Paul Cadmus and then married Cadmus’ sister, Fidelma. Their marriage endured for fifty years, though not very harmoniously. My only complaint about the MoMA show is that it neglects to provide information about Fidelma, an artist herself whose beauty has been mythologized in many photographs of the era. Who was she? Like Kirstein himself, one suspects she was far more vivid and interesting than many of the artists he championed.