The case of Hilma af Klint is among the most fascinating in art history. Born in Sweden in 1862, and raised in a socially established family, she produced what are believed to be the earliest abstract paintings of the modern era. Yet you won’t find her name in art-history textbooks. Instead, Mondrian, Kandinsky, and Malevich, among others, monopolize the credits and remain unchallenged as the avatars of non-objective painting, which supposedly began around 1910.

I wish they could see “Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future,” the radiant and revolutionary new show at the Guggenheim Museum. Trained in Stockholm as a portraitist and landscape painter, af Klint turned to abstraction in 1906, after she was shaken by the death of her younger sister. Together with four female friends (the group was known, conveniently and unmystically, as “The Five”), af Klint conducted séances and made contact with so-called spiritual guides who determined the direction of her art.

That might sound a little flaky to our modern and secularized ears. But it is important to remember that spiritualism was vastly popular at the end of the 19th century, and male artists were not immune to its seductions. Mondrian, for one, was a member of the Dutch Theosophical Society and, like af Klint, viewed his work as a means to a spiritual end, a vehicle for escaping the quotidian world and getting a glimpse of transcendence.

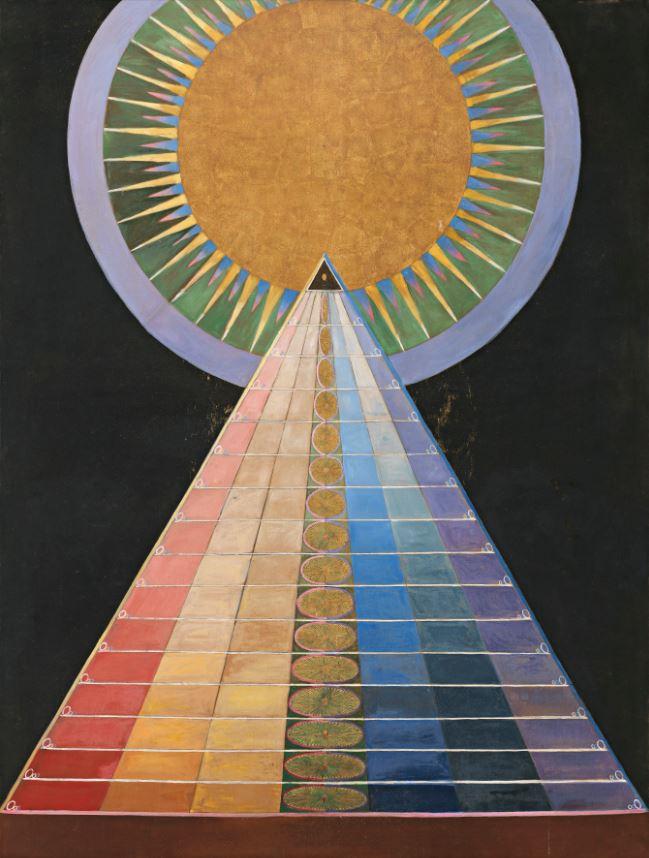

The Guggenheim show opens with a bang – a room ringed by af Klint’s “Ten Largest,” a series of mural-sized, ceiling-high paintings that stun with their lush lavender hues and organic forms. Done in the relatively perishable medium of tempera on paper, the “Ten Largest” track the stages from birth to old age in a style that mingles medical illustration with Jugnedstil curves. Here are egg shapes and petal shapes and the letters of the alphabet inscribed in neat cursive. Here are circles upon circles suggesting realms both anatomical and astronomical. Af Klint conceived of her abstract paintings as decoration for a never-built temple, and not all are equal in quality. Over time, they became schematic and sometimes stiff and lost the flower-power immediacy of the “The Ten Largest.”

Af Klint’s obscurity is partly her own fault. She decreed that her revolutionary experiments in abstraction could not be exhibited for 20 years after her death. The reason, she maintained, was that her Swedish contemporaries were too conservative to understand abstract painting and were likely to denigrate her efforts. Her reluctance to show her work is disappointing, but who knows what she was up against? She minimized her own place in art history and stands in unsettling contrast to generations of male avant-garde artists who devised ways to promote their work, with their meetings and manifestoes and do-it-yourself exhibitions.

At the same time, this show is as radical as a museum exhibition can be – less because of the content of the work than the holes and craters it pokes in the official story of art. It is incredible, after the decades-long apotheosis of Mondrian and Kandinsky, to learn that a woman pioneered abstract panting before them. I hope that textbooks are being re-written as we speak.