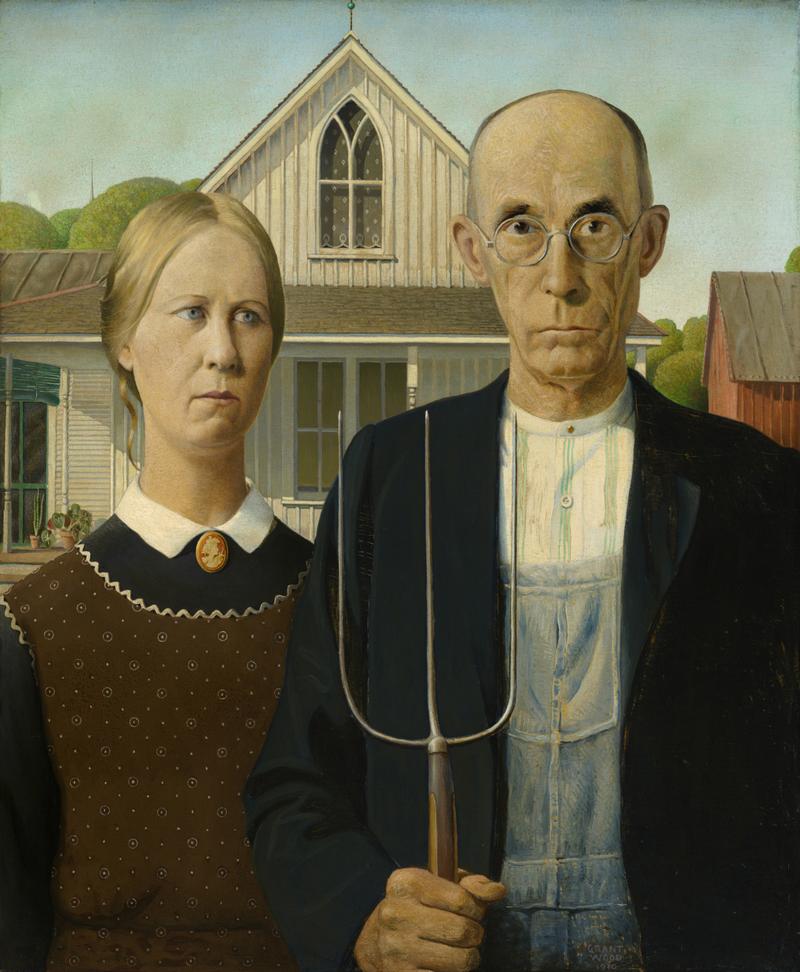

Grant Wood’s “American Gothic” is almost as famous as the Mona Lisa, which is not to say that it’s a painting about a smile. To the contrary, it shows what appears to be a glowering, bespectacled husband and his long-faced wife standing outside a white-painted farmhouse in Iowa. When the painting was first exhibited — in 1930, at the Chicago Art Institute — it became an instant sensation. Viewers were enraptured by this solemn couple, who were believed to personify the resilience and grit needed to lift the country out of the Depression. The two figures appear genuinely miserable. I’ve always thought they look like their favorite farm dog was just run over by a car.

Truth be told, “American Gothic” is less compelling than many of the other paintings in “Grant Wood: American Gothic and Other Fables,” a fascinating retrospective that opens today at the Whitney Museum of American art. Wood, of course, belonged to the Regionalist movement of the 1930s, and he made the people and places of his native Iowa the primary subject of his work. I could gaze forever at his farm scenes, the emerald-green fields planted with neat rows of crops, the lollypop trees that repeat in arresting patterns. Although he was devoted to Midwestern subjects, he visited Europe several times, and his style owes everything to the crisp, detail-laden art of the Northern Renaissance. You can say he combined the local-yokel subject matter of 19th century American folk art with a sparkling Netherlandish precision. He was the Memling of Iowa.

Wood’s current revival is at least partly related to the fashion for gender theory. A new crop of art historians have pegged him as gay and discerned homoerotic content in his imagery. A generation earlier, art historians like Wanda Corn claimed that female curves were submerged in his hills. Personally, I find his work relatively asexual and chaste, and it is probably significant that he painted so many of his landscapes from an overhead, nearly aerial perspective, as if to keep himself at a permanent remove from the things he desired.

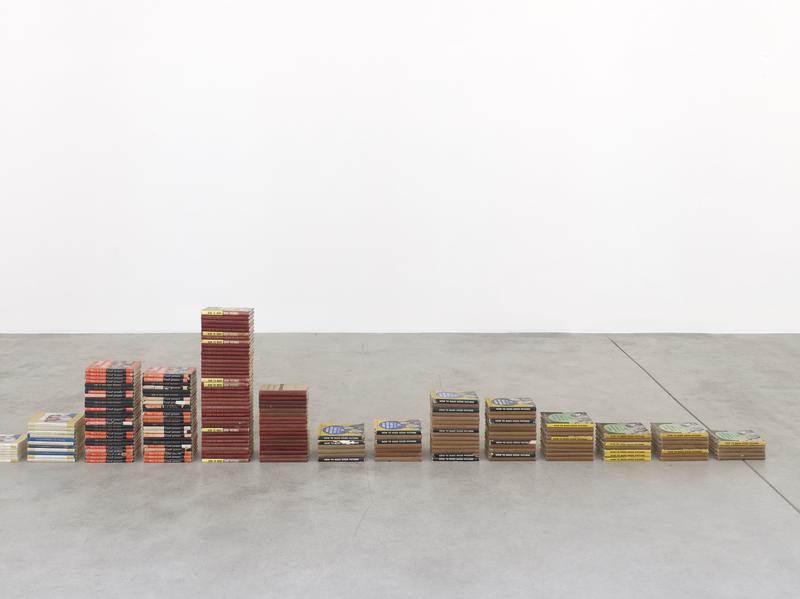

This is a superb moment for the Whitney. The Grant Wood retrospective shares the sprawling fifth floor of the museum with “Zoe Leonard: Survey,” which at first might seem like an odd pairing. Leonard, a New York-based artist born in 1961, specializes in photographs and sculptures that extract a spare and very personal poetry from the orthodoxies of Minimalism.

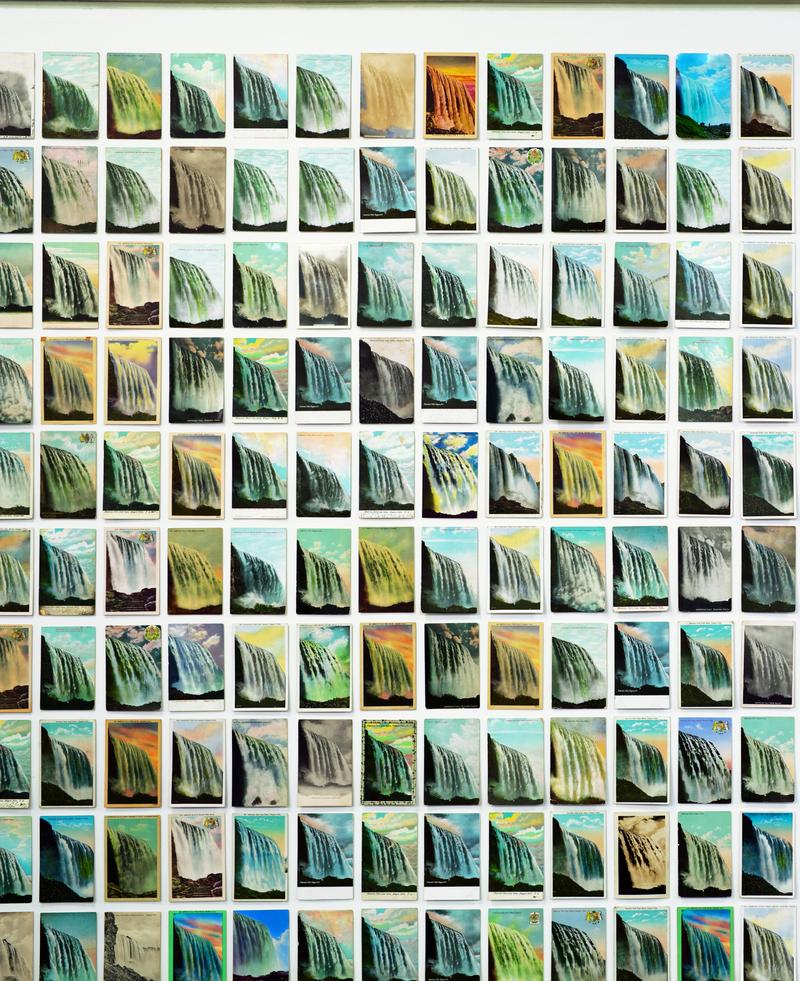

Yet like Grant Wood, Leonard is thinking about the American landscape. Whereas he was concerned about a Midwestern paradise that was vanishing amid economic hardship and industrialization, she is making art in an age when paradises no longer exist. I particularly admired “You See I Am Here After All,” a huge, horizontal installation contrived from thousands of vintage postcards of Niagara Falls. It reminds us that nature is hard to find these days, and even the fields of Iowa are not immune from a consumerist culture that devalues any experience that cannot be packaged, profitized or squeezed between the edges of a post card.