Adam Rhodes, journalist with Investigative Reporters and Editors who writes about how queer people are criminalized in the United States, reports that in New Jersey, tabloid headlines have led to prison housing placements inconsistent with gender identity. And a new investigation from The City reveals that a unit for trans women at Rikers Island has "collapsed" under the Adams administration. Adam Rhodes shares their reporting from New Jersey, and George Joseph, courts reporter for The City, shares his reporting on the NYC Department of Correction's LGBTQ+ Affairs Unit.

→Under Eric Adams, a Rikers Island Unit That Protected Trans Women Has Collapsed

[music]

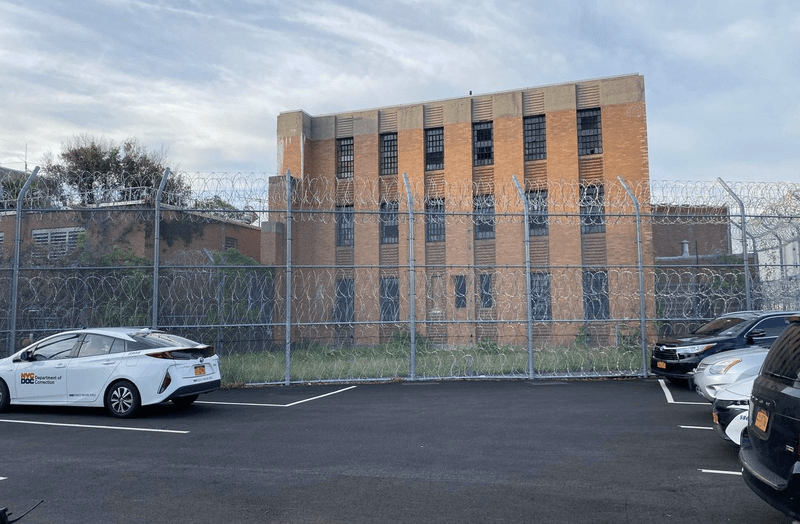

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. When Layleen Polanco died, some of you know that name, while locked in solitary confinement on Rikers Island in June of 2019. New York City looked to be stepping up its efforts to offer support for trans inmates efforts that had already been underway. Now in New York City and in New Jersey, trans-incarcerated women are being housed in jails and prisons inconsistent with their own gender identities. In prisons, our region looks to be moving in the wrong direction.

In New Jersey, protections have been stripped away, and in New York, a unit that not only housed trans women but also offered important community programming has been all but dismantled. All this has meant that here in the city and in the garden state, trans women are being incarcerated at jails inconsistent with their own gender identities. We'll take a closer look now with Adam Rhodes, journalist with Investigative Reporters and Editors who writes about how queer people are criminalized in the US in general.

They have a story about what's happening in New Jersey on the site, the appeal. Also joining us, George Joseph Courts reporter for the news organization, The City, out with a new investigation about how the New York City Department of Corrections LGBTQ+ Affairs Unit has been gutted under the new Commissioner Louis Molina under Eric Adams. Hi Adam. Hi, George. Thanks so much for joining us. George, I'll just give you props for all the great work you did when you were a WNYC reporter, and glad to see you're still at it out there with The City. Welcome back to WNYC.

George Joseph: Thanks, Brian. It's great to be back. Good morning.

Adam Rhodes: Hey, good morning.

Brian Lehrer: George, let's start in New York City. How did the Department of Corrections LGBTQ Affairs Unit come about and in what ways did it used to support trans inmates?

George Joseph: Sure, Brian. Trans women who were in jails and prisons are among the most vulnerable populations in custody. There are many more times likely to be sexually assaulted than other incarcerated people. During the de Blasio administration, the administration took a series of steps to try to increase safety for that population, including by creating specialized housing for it, by creating policies that would help them get into gender-aligned housing.

Lastly, by creating this unit which you referenced which did a lot of innovative things like launching programming specific to the community, opportunities to create pride, posters to do a ball, all kinds of things. Probably most importantly, having a say in housing decisions for those detainees. What we've seen since the Adams administration came in is that that unit has collapsed. It only has one staff member left currently which has been the case for several months, and it does next to no programming according to people who work and live in the jails who we interviewed.

Brian Lehrer: If a decade ago New York was aiming to be a leader in supporting trans people incarcerated in its jails, how did things get so bad?

George Joseph: Very quickly after Louis Molina, Eric Adams' Department of Corrections Commissioner came into power, he fired several top staffers who had supported that LGBTQ unit. Without that higher level support, what happened was a lot of the middle management who were more conservative, more traditional law enforcement started having more say in housing decisions for trans woman applicants who were attempting to go to female housing units on Rikers Island.

As a result, this unit became so consumed in clashes with that middle management that it lost the ability and the energy capacity to do programming. As a result, multiple staffers quit in protest leaving the unit with just one person and the department has not hired anyone else since then.

Brian Lehrer: Before we bring in Adam and talk about the New Jersey corollary to this, are these acts of hate, are these acts of not supporting the existence or the positive identification of trans people in the Adams administration, or is this just part of Riker's dysfunction overall as things are falling apart and fraying in so many ways? What's behind it?

George Joseph: It's really hard to get at questions of potential animus in someone's head. However, what we can say, Brian, is that we documented numerous cases with medical paperwork, DOC paperwork, interviews with current staff there as well as incarcerated women, and found numerous cases of trans women who were more or less being left behind in male jails, stranded even after pretty egregious cases of reported violence.

Just to give you one example, there was a woman that we profile in this story named Tamara Harrison, a trans woman who was stuck in male jails late last year on Rikers Island, reported being groped repeatedly by a fellow detainee. That incident drove her to cut both of her arms, but even after that jail officials kept her in male housing. The LGBTQ unit which at that point only had one staff member attempted to get her into a medical unit where she'd have better access to her hormone therapy treatment but was unable to do so which reflects their lack of power in the agency today.

After that, a day later, she swallowed batteries yet another self-harm attempt. The department continued to keep her in male jail facilities for weeks further, she cut herself a third time, the most serious cut that she had which required stitches. Then finally after that, she was moved to female housing at the Rose M Singer Center where today she says she's much happier and feels much safer.

Brian Lehrer: Let's bring in Adam Rhodes, journalist with investigative reporters and editors who writes about how queer people are criminalized in the US. Their story is about what's happening in New Jersey on the news site The Appeal. Adam, similar rollbacks, right? Tell us what's happening in the garden state.

Adam Rhodes: Hey, thanks for having me. Yes. In New Jersey, late last year, prison officials rolled back a policy that created a presumption that trans-incarcerated people would be housed and facilities that aligned with their gender identity. Now under this rolled-back policy, the new policy gives corrections officials much more leeway to deny those gender-affirming housing placements, particularly in light of some controversial pregnancies at the women's prison in the state.

Brian Lehrer: Controversial pregnancies meaning what, and affected policy how?

Adam Rhodes: The controversial pregnancies at the state's only women's prison were attributed to a trans woman at the facility, Demi Minor. The pregnancies were consensual. There was nothing to suggest that the relationships were out of pocket or anything, but the pregnancies caused a media firestorm that really ignited a lot of debates about whether trans women or the treating trans women with respect and housing them in facilities that align with their gender identity puts cisgender women at risk which is not the case. As a result of that firestorm, the policy was changed.

Brian Lehrer: What would you say to people who might think it's a close call to put trans women who are people who are born men in a unit with women born women if there's maybe a tendency more on the part of men to act inappropriately that that's a dangerous thing to do for the women. That they're trying to do this out of a goal of protecting women in jails rather than to discriminate against trans women. It's a close call. Some people probably have that question. What would your response be?

Adam Rhodes: I think frankly, those kinds of concerns to me are rooted in outdated ideas that trans women are really just men who are transitioning into women. Trans women want to be housed in facilities that align with their identity not to increase their likelihood of sexual contact or anything like that. They want to be free of abuse, of assault of violence. Frankly, it's not the trans women in these facilities that are hurting the women, it's the prison officials that are violently beating these women.

In the facility that Demi Minor was removed from 30 plus corrections officers were recently suspended, and about more than a dozen officers were charged for want and violence at the facility. Again, the safety threat here is not the trans woman who wanted to be treated with dignity. It's the system that is perpetuating this harm.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, if anybody has any experience with being a trans woman incarcerated in a jail or a prison and wants to talk about what's right and maybe what's right versus what they're actually doing, especially as things seem to be going down hill in both New York and New Jersey at the same time, help us report this story. If anybody has a question for our guests, George Joseph from the news organization The City on the New York side, Adam Rhodes from Investigative Reporters and Editors on the New Jersey side. (212)-433-WNYC, (212)-433-9692, or tweet @Brianlehrer. Also joining us for a few minutes is Kels Savage, a former services coordinator who worked in the New York City Department of Correction's LGBTQ+ Affairs Unit. Kels, thank you for giving us a few minutes. Welcome to the show.

Kels Savage: Hi, thank you for having me.

Brian Lehrer: You've worked in this unit, so you can report from the inside, not even as merely a journalist. As you see it, how did this unit support trans inmates? What were its greatest strains? Then we'll talk about what may have changed.

Kels Savage: Well, in the beginning, we immediately hit the ground running. It was a rocky start because of COVID restrictions. While those COVID restrictions were slowly being lifted, we were able to do a lot of programming. I started in May 2021, and immediately I was in a unit that mainly housed transgender women, and we were creating a mural together. That was how I first met them. Soon after we were creating signs together to carry on the behalf of LGBTQIA+ individuals in custody to the Pride parade.

As our unit began to really understand a lot of the policies and ways that we could carry out a lot of services, we started to really-- I felt that we were really creating some change. I was very skeptical about starting to work at the DOC in the beginning, but fundamentally, I felt like there was a shift with the creation of this unit. We were able to do things like bail individuals out that couldn't make bail so that they could work on their case. We were able to help facilitate name changes, made sure that individuals were receiving treatment, began working on whatever medical advancements that they wanted.

Beyond Rikers, if an individual was sentenced we were able to work on their behalf to make sure that they were placed in a women's prison and not a male's prison. A lot of work, including, we had a program called the Ambassadors Initiative, where we trained staff, both uniform and non-uniform staff to really understand a lot of the terminology, the policies, how to really advocate on behalf of the LGBTQIA+ people in custody. We had a small team, and there's about 6,000 people in custody, so we were really trying to shift the culture of how LGBTQIA+ people were treated by having a deeper understanding, especially with the statistics of the transgender and non-binary, gender-nonconforming individuals being disproportionately at a higher risk of assault.

Brian Lehrer: Of self-harm, in particular.

Kels Savage: In the beginning, I felt-- Yes, self-harm, most definitely.

Brian Lehrer: Were you stationed inside Rikers, at Rikers?

Kels Savage: Yes, I was in all facilities, but my main facility was Rose M. Singer, which is the women's jail, and also where we had a special considerations unit that was there to house transgender and gender-nonconforming, non-binary individuals.

Brian Lehrer: What got you to the point where you decided you need to resign and protest, because that's what you did, right?

Kels Savage: Yes, I did. I got to the point where, especially when there was the administrative shift, when-- Our unit first started in the programs division, and then we were moved to chief of staff under Dana Wax. A lot of things that we had been working on, a new directive, there has been a training that, as far as I know, has not been implemented. We had all these things ready to go, felt like we were really building more of a voice, I was being heard, but once Dana Wax was let go and Sarena Townsend was abruptly fired, that shift really was felt, it was tangible.

Very clearly a lot of the committee calls that we were on to help make determinations for the safety of the housing that aligned with individuals' gender, we were silenced, a lot of our reasoning behind helping individuals was silenced. The administrative change really took away our voice, and it got to the point where I was complicit. I was complicit with things that I didn't agree with. I really felt I had no choice but to resign. I put all of this in my letter of resignation, which I submitted to the agency.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you for sharing it with us. Kels Savage, former services coordinator, who worked in the New York City Department of Correction's LGBTQ+ Affairs Unit. Thank you for coming on with us for a few minutes. Joining us next for a few minutes is Mik Kinkead, an attorney with The Legal Aid Society's LGBTQ+ Law and Policy Unit. Mik, thank you for giving us a few minutes. Welcome to WNYC.

Mik Kinkead: Absolutely. Thank you so much for having me.

Brian Lehrer: You were just hearing Kels describe the sea change in the LGBTQ+ Affairs Unit. In what capacity did you work with that unit, and what is The Legal Aid Society trying to do to fix these problems?

Mik Kinkead: I actually started to get involved with TGNCNBI people on Rikers in 2015. That was when they opened the Transgender Housing Unit, which, at the time, was in a men's jail, at MBC. I went in and I thought classes there, and I represented some of the folks who were in that unit. I've been meeting with the department in various different capacities since 2015. Then, 2019, a month after the death of Layleen Polanco in custody, this unit was publicly announced.

They had hired Elizabeth Munsky as the director. I believe she worked alone for about a year, and then Kels joined and a few other individuals joined. As someone who had been doing this work since 2015, that was a moment where we thought, "Oh, there might actually be a difference here. We might actually be able to make a change for our clients. They might not go to Rikers and immediately face sexual violence." Otherwise, it's almost 100% guaranteed they will if they go to the wrong facility. Then, I think, a little bit like what Kels was saying, I heard on the other side-- I'm on the task force for TGNCNBI people in the city jail [unintelligible 00:18:32] the city council task force.

Dana Wax sat on that task force. When she was abruptly fired, we were never informed. I would send e-mails and be like, "Dana, we missed you at the meeting. Could you possibly give me an e-mail update on what's happening?" I didn't even get an e-mail bounceback. It just went to the ether. I think the moment that we knew things were very, very bad was in April of 2022. We had been told that another special considerations unit was opening in a men's facility.

This is something we had been asking for for a very, very long time. We had been saying, "Gay cisgender men, bisexual cisgender men, and trans men need a safe space within the men's jail." They told us that's exactly what they were doing, they're going to open that unit. They did open the unit and immediately put trans women who wanted to be at the women's jail into that unit. We protested, we called, we sent e-mails saying, "This is not acceptable." [crosstalk]

Brian Lehrer: Why? Why do you think they did it? Why would they so blatantly go against the identified gender of incarcerated people and place them against their will in a different unit?

Mik Kinkead: Quite frankly. If anyone is able to see the City Council hearing yesterday on the report of the task force, I think it is because there's still a lack of belief that transgender people are who we say we are. Despite the fact that city human rights law covers us in every other aspect, it covers us in accommodations and in employment, says you cannot actually question a person's gender identity in jail. The city's viewpoint is that those laws don't apply in a jail setting. Obviously, I disagree with that. I think they do but because there is [crosstalk]

Brian Lehrer: Are you in court to try to establish that consistency?

Mik Kinkead: We've been working with the Commission on Human Rights, and in fact, I made this point at the hearing yesterday, the move of the transgender housing unit from the men's jail to the women's jail at Rose came out of a lawsuit. It came out of the pre-pleading part because I believe the city was so desperate to not actually have a lawsuit of this nature on their hands, that this concession was made.

Brian Lehrer: George Joseph, if you watched this city council hearing yesterday on this issue after they grilled Corrections Commissioner Molina, is it something that city council can do something about? Can they pass a law and mandate proper treatment for trans women inmates in New York City jails in prisons?

George Joseph: Yes, Brian, I covered that hearing yesterday. What was pretty clear from the hearing is that Commissioner Molina more or less stood his ground. He said there was no culture problem at the Department of Corrections. He did not make promises to follow any of the changes that advocates have been calling for. Although he did say they would consider things and they were open general language.

As a result of that, city council members are proposing several bills in this area. One of those bills would create a review board, which would involve the Board of Corrections, the Department's Watchdog Agency so that there can be appeals when there are disagreements in housing decisions. Also, so that incarcerated people who are denied a housing transfer request will have information about why they have allegedly been denied.

More dramatically though at the state level, there is a pending bill, which would create a presumption of gender alignment for incarcerated people in the housing facilities that they are going to be placed in unless they choose to opt out of that placement. There are several bills at the local and state level that could make a change possibly here.

Brian Lehrer: Adam, I'll give you the last word in this segment. Is this up to Governor Murphy? Does he need to show his bonafides in this respect? I think he says he's for the rights of LGBTQ+ people. Is this up to Governor Murphy to make the change in New Jersey prisons, so people are treated consistent with their identities?

Adam Rhodes: Yes, it definitely appears that it's up to the people with more power than the DOC Commissioner to make these changes. Governor Murphy state legislators, because without them, this rollback happened.

Brian Lehrer: Adam Rhodes, George Joseph, thank you very much, for coming on the show and shedding light on this story and how things are going in the wrong direction in this respect in both New York and New Jersey, and making sure people know. Thank you very much.

George Joseph: Thank you, Brian.

Adam Rhodes: Thank you.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.