SchoolBook

SchoolBook

Demand for School Integration Leads to Massive 1964 Boycott — In New York City

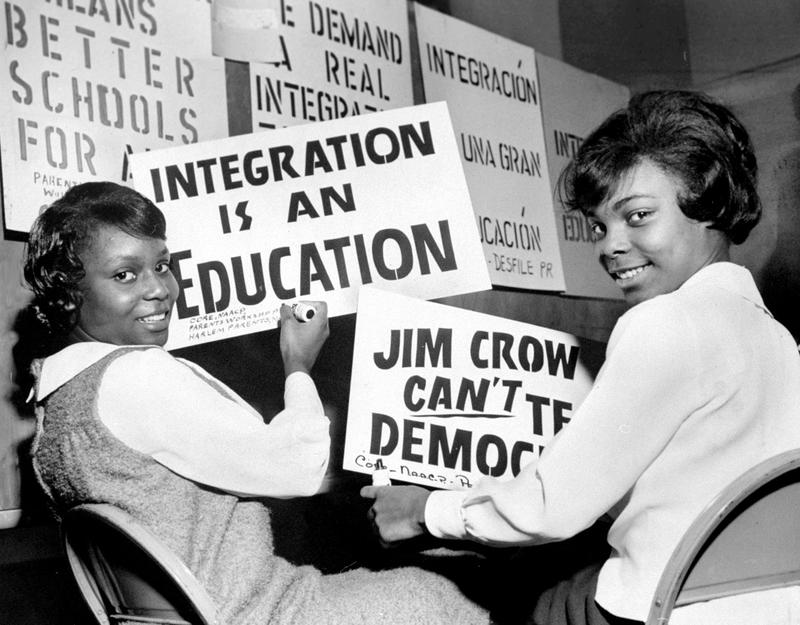

After hearing too many "vague promises" from the New York City Board of Education to integrate the schools, civil rights activists in 1964 called for swift action: desegregate the city's schools and improve the inferior conditions of many that enrolled black and Latino students.

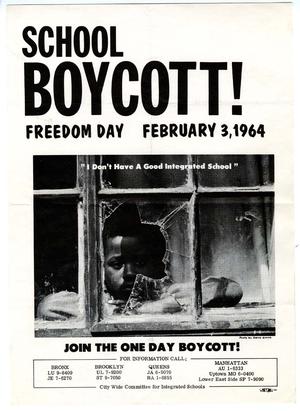

To force the issue, they staged a one-day school boycott on Feb. 3, when approximately 460,000 students refused to go to school.

Even adjusting for the typical absentee rate at the time, the school boycott was the largest civil rights protest in U.S. history. It didn't happen in the South; it happened in New York City, where the mostly white elected officials and Board of Education members said they believed in integrated education.

Yet, little came of the boycott, and the activists' demands resonate still.

A 2014 UCLA study found that New York City has some of the most segregated schools in the country, with high concentrations of black and Latino students isolated in their neighborhood schools. Researchers from The New School have more recently shed light on how schools can remain segregated, even as neighborhoods diversify.

Changing demographics have forced families and education officials to confront antiquated zoning practices that assign students based on their home address. Small-bore changes have come on an as-needed basis, as in the case of a Brooklyn school rezoning. City leaders have not committed to reviewing or changing school zone lines or admission rules on a citywide level. Instead, they argue, school-based pilot programs and the current mayor's affordable housing plans will help integrate many schools in the massive system.

These present-day issues are stark reminders that New York never adequately addressed segregation, said Matt Delmont, author of the forthcoming book "Why Busing Failed."

"We want to celebrate civil rights as something that was resolved and battles that were won in the 1960s," said Delmont, an associate professor of history at Arizona State University.

In the South, very distinct battles were won, he said. But northern cities largely stagnated.

"We never resolved the problems that were going on in the 1950s and 1960s in the North, and we're still dealing with those repercussions today."

The 1964 Boycott

The boycott came during a time of inspired protest, six months after the March on Washington.

Bayard Rustin, who organized the March on Washington, helped direct the New York City boycott. But its lead planner was Milton Galamison, a civil rights activist and pastor of Siloam Presbyterian Church in Bedford-Stuyvesant, who had been pushing for years for more integrated schools in New York.

Segregated schools had been illegal in New York City since 1920, according to Board of Education reports. But housing patterns and segregation ensured a racially segregated school system, and an unequal one.

In 1964, schools that enrolled mostly black and Latino students tended to have inferior facilities, less experienced teachers and severe overcrowding. Some schools were so overcrowded that they operated on split shifts, with the school day lasting only four hours for students.

"Nobody can do these children more harm than these children are being done everyday in this public school system," said Galamison. "And in my opinion, the refusal of the board to have already taken immediate steps to correct these evils is a disgrace and a crime.”

The Board of Education did have a plan, though. In fact, members released a blueprint for integrating the schools just days before the boycott in 1964.

The plan, which would be implemented over three years, called for rezoning a small percentage of schools, improving the educational quality of schools that served mostly black and Latino students and relieving school overcrowding in order to give each student a full school day.

Galamison and other civil rights activists said the plan was not comprehensive enough. Many white parents on the other hand, even those who extolled integration efforts in theory, thought the plan went too far.

White Parents Push Back

When it came to changes on a neighborhood level, parents protested in fiery community meetings. They feared widespread busing, and they began to organize.

A group called Parents and Taxpayers formed to protect the "neighborhood school" concept. They never spoke openly about race, or against the call for equal education. They centered their arguments on the importance of children attending schools closest to their homes.

In early March, 1964, some 15,000 white parents marched to City Hall holding placards reading "Bussing Creates Fussing" and "Don't Let the Courts Dictate Our Children."

"The only time the protests emerged and the only time they started using the language of 'neighborhood schools' was when there was a possibility of African-American or Puerto Rican students entering schools that had formerly been predominantly white," Delmont said.

Civil rights activists and education officials alike were frustrated. Activists, like Galamison, criticized the city for failing to aggressively tackle segregation; education officials believed activists were making impossible demands on a short timetable.

By the late 1960s, Galamison and other civil rights leaders shifted their focus: instead of pushing for integration, they pushed for local control of the schools.

Integration as a Goal

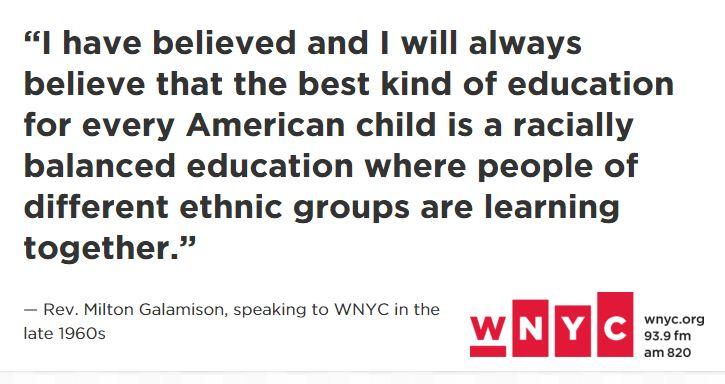

Although local control was a change of strategy, Galamison indicated that it was not the end game; it was a placeholder. On a WNYC radio broadcast, believed to have aired in 1969, Galamison reiterated his call for integration.

"I have believed, and I continue to believe, and perhaps I will always believe that the best kind of education for every American child is a racially balanced education where people of different ethnic groups are learning together."

Searching through city documents from that time and earlier, it was clear that many city officials sought the same thing.

In 1955, on the heels of the Brown versus Board of Education Supreme Court decision declaring segregated schools inherently unequal, the city's Board of Education formed a Commission on Integration.

"If the City was to obey the spirit of the Supreme Court's decision it must take immediate steps to put its own educational house in order," the commission said in its final report in 1958.

The report represented three years of work studying and making recommendations related to school facilities, zoning, teacher assignments and curriculum, among others.

The final report read:

"The task we have set them — to march, 'with all deliberate speed,' on the road toward the integration of our schools — is not an easy one. But the terrain has been surveyed, the route mapped, and, without any question, the people of the City of New York want to travel that road to the end."

Now, elected leaders and city residents must decide if those plans are still worth implementing.