Neil deGrasse Tyson, astrophysicist and director of the Hayden Planetarium at the American Museum of Natural History, a host of the StarTalk Radio podcasts, one of the authors of A Brief Welcome to the Universe: A Pocket-Sized Tour (Princeton University Press, 2021), and the author of Cosmic Queries: StarTalk's Guide to Who We Are, How We Got Here, and Where We're Going (National Geographic, 2021), talks about space travel and the need for science education.

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again everyone. At 11 o'clock this is WNYC FM HD and AM, New York, WNJT-FM 88.1, Trenton, WNJP 88.5, Sussex, WNJY 89.3, Sussex WNJY 89.3 Netcong, and WNJO 90.3, Toms River. We are in New York and New Jersey public radio, and we continue with some special programming during this Membership Drive Week. When you want to talk about outer space and the cosmos, who would you turn to first, Jeff Bezos or Neil deGrasse Tyson? Okay, maybe William Shatner, but forget him for a minute.

We have made our choice and we're delighted to have astrophysicist and America's favorite space geek, Neil deGrasse Tyson back with us for a few minutes this morning at a time when space travel is in the news more than any time in recent memory. There's the recent Bezos trip, the private SpaceX trip, last month to the William Shatner trip, and the return on Sunday, did you hear about this, of a Russian actor and director from the International Space Station after spending 12 days making what's being described as the first scenes ever shot in space for a full-length movie drama.

Neil deGrasse Tyson is an astrophysicist and Director of the Hayden Planetarium at the American Museum of Natural History. Host of the StarTalk Radio podcasts. One of the authors of A Brief Welcome to the Universe: A Pocket-Sized Tour brand new book and author of Cosmic Queries: StarTalk's Guide to Who We Are, How We Got Here, and Where We're Going, published just earlier this year. Always great to have you, Dr. Tyson, welcome back to WNYC.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Thanks, Brian, and please call me Neil. It's been good to be back. It's been too long. I haven't seen you since COVID, so this is long overdue.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you, and I'm so delighted you're here. You're a scientist, not a travel agent, but what do you think about the current burst of private spaceflights that the media tend to call space tourism?

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Well, first, it is space tourism. They're average, rich people. [chuckles] That's an important distinction. It's tourism for rich people at the moment, but I don't see any reason why we wouldn't collectively foresee the day where the price of that trip drops sufficiently so that maybe you'd save up several of your own vacation budgets to pull it together and then take one trip into space. I can see that happening, maybe within even a decade, but certainly within the next 20, 30 years.

Brian Lehrer: Well, if anyone should be allowed to ride on one of these trips, I would think you would be near the top of the list. Do you have any plans or aspirations?

Neil deGrasse Tyson: No. I've joked with Elon. People said, "Will you fly to Mars on Elon's rocket?" I half-jokingly say, "Yes, but only after he sends his mother and brings her back safely, just to affirm that it's safe." With these, the suborbital trips, Jeff Bezos, put his own flesh into that risk to demonstrate that it's safe, and so we're rapidly approaching that point. For me, to either go into suborbital launch, which is what Bezos in Branson did, or even orbital, which is what SpaceX has been doing,

File name: bl101921cpod.mp3

for me, that's boldly going where hundreds have gone before.

For me, as an astrophysicist, the universe is much larger to me than low Earth orbit. If I'm going to go into space, send me to the moon, Mars, or beyond, someplace. Give me a destination far that I can look forward to and watch it grow in the front windshield.

Brian Lehrer: Well, you know what I was wondering as I was thinking this morning about you coming on today? If you got up there, if Neil deGrasse Tyson got up there, knowing everything you already know, what would you be looking to observe or experience?

Neil deGrasse Tyson: I would want to see and just emotionally feel how thin our atmosphere actually is. I know what it is intellectually, in fact, this famous Karman line that has been established as the boundary between Earth and Space, which is not particularly high up above Earth's surface. You can do the math on this. If you take Earth and shrink it to a schoolroom globe, just so you get a sense of this, and then take the thickness of two dimes, that's how high above earth surface Branson and Bezos went with their suborbital flights.

At that distance, you're not seeing a pale blue dot in the distance as Carl Sagan had waxed poetic of the image from Voyager. You're not going to see the curvature of the earth. None of that's going to happen, but you will ascend above the thickness of Earth's atmosphere, sufficient amounts of its thickness so that the blue sky disappears and it becomes the darkness of space, even when the sun is out. That's a remarkable transition to experience.

Frankly, we experience that every evening at sunset, [chuckles] the stars come out, but you get to see this in a matter of moments. That's considered the boundary to space, but that's also the thickness of our atmosphere, of our material atmosphere. Our atmosphere is to Earth as the skin of an apple is to an apple. That's a lesson that not enough people have, and we should all have it.

Brian Lehrer: Really interesting how thin that is. Were you aware of that movie shoot, what they're calling the first movie shoot in space for a feature-length drama? Is there anything they can do visually, do you think, in actual space that they couldn't simulate on earth in Hollywood?

Neil deGrasse Tyson: For example, if you take the movie Gravity with Sandra Bullock, as the star, they captured a lot of zero-G phenomena in the capsule. The movie is called Gravity, it really should have been called zero gravity because the whole movie was taking place in orbit. They use special effects and wires, and visual effects and this thing, all combined, but there are certain things that they missed. For example, Sandra Bullock's bangs always pointed downwards in every scene, and that's not what would happen if she would film actually in space or in orbit.

The bangs are supposed to be floating randomly, so they missed that. You don't have to worry about remembering what to make look zero-G when you're actually in zero-G. I did not know about this fellow who was the filmmaker. I can tell you that, as

space access becomes available to everyone, I want you to send poets, send illustrators, send artists of all stripes because then they will come back and enable space to infuse into their own tributaries into the main rivers of civilization. Space belongs to us all, not just the privileged rich, or "the right stuff," that we had all read about from the 1960s.

Brian Lehrer: You're saying, even as an astrophysicist, it shouldn't just belong to the scientist?

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Oh, definitely not. In fact, what we should all do, again a half-joke, but that means I'm half-serious, the first voyagers to space should be all the politicians.

Brian Lehrer: That the one-way trip.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: [laughs] Depends on who your favorite politician is.

Brian Lehrer: You let poets and the artists come back. Neil deGrasse Tyson with us. I was reading today about the forthcoming recommendations for NASA and the field of astronomy, in general, from the National Research Council, known as the Decadal, is that how you say it?

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Decadal.

Brian Lehrer: Decadal, referring to 10 years, Decadal. They release one only every 10 years. The new one is expected to include diversity goals when only a tiny fraction of astronomy PhDs, even now, go to people from underrepresented groups. The report is expected to address systemic barriers. I'm curious if you have any thoughts on how to improve the field in this way.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Thanks for asking about that. First, the decadal survey is one of our proudest things we do as a community of astrophysicists. We've been doing it at least since the 1960s, maybe even a decade-

Brian Lehrer: Somebody's got a nice spacey ring tone going there. Sorry, that was in our studio. We fixed that now. Sorry, Neil go ahead.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: [chuckles] At least it was a spacey ringtone. This decadal survey, we gathered together the most trusted among us and the most respected among us. They gather, they bulkheads, they put forth projects that are large and expensive and require a lot of buy-in from the broader community, and then they get prioritized and presented to Congress. Whatever money gets spent, will then get spent in that order.

The Hubble Telescope emerged from a decadal survey. The very Large Array Telescope in New Mexico, the one famously shown behind Jodie Foster when she communicates with aliens, that came out of a decadal survey,

It's very important, then it's long overdue, I think, for a commitment to accessibility,

File name: bl101921cpod.mp3

diversity, inclusion, be made a priority. Yes, I'm glad. I should be. I served on a decade of survey back in 2010. That included discussions about how many of us are actually bringing science to the public so the public can participate, at least vicariously or emotionally or intellectually in our activities which, in fact, they had paid for as taxpayers for NASA, for the National Science Foundation and the like. These reports have always had a social-cultural dimension to them in addition to the science priorities.

Brian Lehrer: Your new book, A Brief Welcome to the Universe: A pocket-Size Tour just out. It is really small. If anybody wanted the Neil deGrasse Tyson intro, tell me if you think I'm characterizing this fairly, that you can do almost over lunch. It's a great way to start or to give to your kid, probably even. What's the most common question you get asked by laypeople that you tried to answer in this book?

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Those are two different things. There's what I'm often asked and then there's what I'm often asked that landed in the book. We decide-- I don't know if this, I am still hounded, no pun intended, by Pluto. I had a role.

Brian Lehrer: You mean like planet or no planet?

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Exactly, and I would've thought all the elementary school kids who sent me hate mail back in 2005 were grown up now and had other priorities, but apparently not. I'd still get on my internet feeds and things. There's a whole chapter in there on just what happened with Pluto and why, but there are other things in there because I have two co-authors, two people I taught a class with at Princeton University.

Out of that class, we wrote a textbook, and from that textbook became this book, so that everyone can have a little taste of what goes on in the Intro Astrophysics classes in the Ivy League.

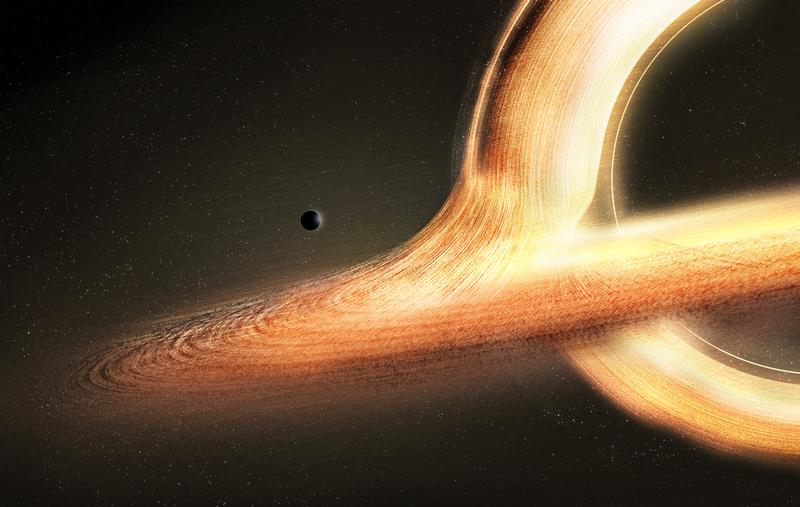

I talk about the size and scale of the universe. Pluto is in there, multiverse. The monstrous black hole in the center of the galaxy, which just got Nobel Prizes, not this year, but in the previous year. Nobel Prizes awarded for their discovery. There's really cool science cherry-picked just to be singular, tasty, and mind-blowing. We're very proud of it, and it really actually fits in your pocket. It's a pocket-size story. We're quite impressed. We're very happy with it.

Brian Lehrer: I can't wait to get mine. Last question, how's the planetarium? Are you open in person again and what's happening there?

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Thanks for asking. Yes, we were following guidelines, not only from the CDC but from the city and at the state levels as well. They had very, very carefully laid out instructions of how to open theaters, how to open large spaces for the public. We've been following all of those rules. We're open and we have-- Huge crowds are coming back with new exhibits. We just opened a whole exhibit. We redid the mineral hall. Oh my gosh, that's one of the great attractions. Maybe second only to the big tooth dinosaurs.

I would say the mineral-- To the planetarium itself, the mineral hall, just minerals and

gems. Oh my gosh, it's completely reconceived and with new minerals on display and crystals. People have been rapping about it. It's still there. I heard you describe in your fundraising efforts that you cover local news and local information, and anybody local knows the American Museum of Natural History and the Hayden Planetarium. It's part of our childhood, it's part of our adulthood, bringing our kids. We're still there and I think we're better than ever.

Brian Lehrer: Long may it thrive, long may you thrive. Neil deGrasse Tyson's latest book is A Brief Welcome to the Universe: A pocket-Size Tour. You can hear him on the Star Talk Radio Podcast, and, of course, he still runs the planetarium. Neil, this was great. Thank you so much. Talk to you again soon I hope.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Good to have you, sir. Thank you,

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. More to come.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.