A proposal to end the test that determines admission to some of the city’s top high schools has drawn intense debate from elected officials, alumni groups, advocacy organizations, and newly minted parent activists. While some decry the test as a scion of segregation and others uphold it as a bulwark of meritocracy, the eighth graders who will be taking it this weekend have mostly kept their heads down and studied.

A week before the test, 13-year-old Sarah Ibrahim stepped out of her test prep class at A+ Academy in Sunset Park still confused about some aspects of triangle geometry, but unwilling to review the formulas that might be of use on the math portion of the test, especially since students can't use calculators on the three-hour standardized test.

“I feel like if I go over more information my brain will explode,” she said with a laugh.

Although the test was changed last year to better align with curriculum taught in school, students like Sarah said they’ve had to learn new material in addition to honing their test-taking techniques. Last year, about 30,000 students competed for just over 5,000 specialized high school seats.

Sarah, a student at Dyker Heights Intermediate School, exuded exuberance despite the stakes. She’s foregone extracurricular activities and even the TV shows she used to watch with her brothers because of her singular focus on preparing for the specialized high school test, or SHSAT.

“She doesn't mind, she's determined, she's happy,” said Sarah’s mom, Akthari Jahan, who came to pick her up in the family SUV.

Akthari said high-stakes tests were a major part of education in her native Bangladesh, and yet, she worried that the SHSAT puts too much pressure on students. She said she reminded Sarah that she’ll have plenty of good options even she doesn’t get into a specialized high school: “You’re ultimate goal is what you want to be in the future. A specialized high school is not the ticket for your good future.”

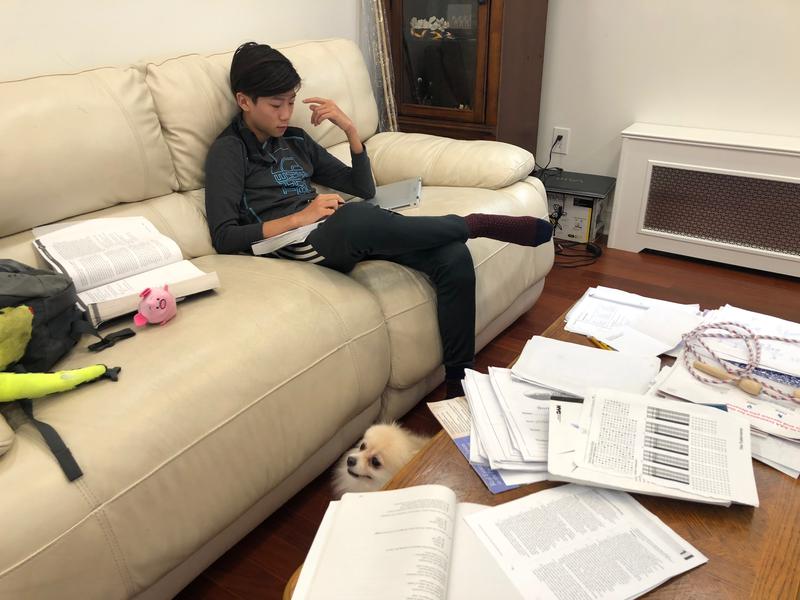

Derek Zang said his dad tells him the same thing, but he knows his parents would be happy to see him follow his older brother to Stuyvesant High School. The J.H.S. 190 student spent much of the last few months plopped on the couch in his Forest Hills home surrounded by SHSAT workbooks. He even plowed through one of them on a family vacation.

“You see everybody else and how they're spending their time,” he said. “They're all having fun right now but I know that in a few months some of them aren’t going to be as happy as they are are now, so that's kind of a motivation.”

Students might rely on a competitive spirit, a healthy dose of peer pressure, and a narrow focus on their goals to put in the time needed to study. Some parents have their own reasons to push their children to study.

Over breakfast at a Clinton Hill diner, Auressa Simmons said she invested time and money in test prep for her daughter, Anaiyah. Less than 5 percent of those admitted to specialized high schools last year are black, even though about one-fourth of all New York City students are black. Few black families like theirs are aware of the extensive study required for the test; Auressa took it herself when she was in eighth grade but didn't land a spot in a specialized high school.

She said she found it hard to strike a balance between encouraging Anaiyah to study without overwhelming her.

“That's where my struggle is,” she said, looking at her daughter. “I want this for you, but I can't want this for you more than you want it for yourself.”

Anaiyah, who goes to the Dock Street School, said she appreciated all her mother did to support her, but worried she’s taken on an unhealthy dose of stress for herself.