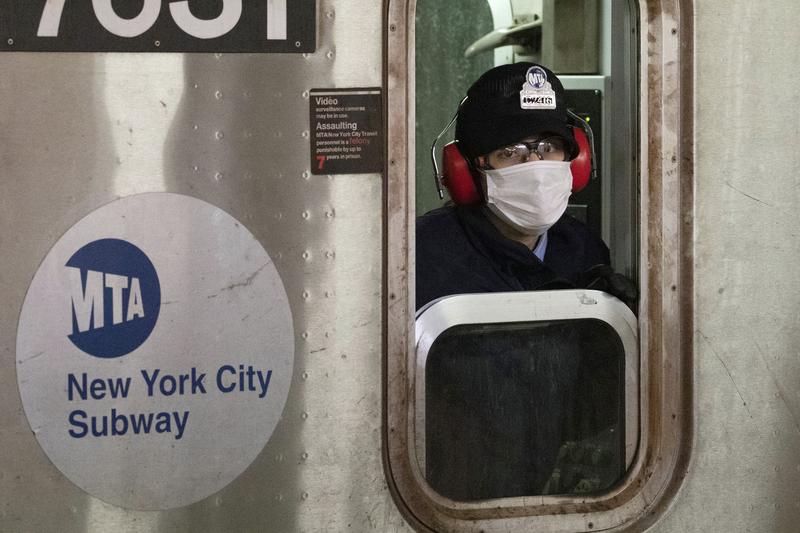

( Mark Lennihan / AP Photo )

Eric Klinenberg, professor in the social sciences and director of the Institute for Public Knowledge at New York University and the author of 2020: One City, Seven People, and the Year Everything Changed (Knopf, 2024), tells the story of New York in 2020 through the lens of seven New Yorkers, and talks about the ongoing effect of that traumatic year.

→ Eric Klinenberg will talk about the book "2020: One City, Seven People, and the Year Everything Changed" with Columbia history professor Kim Phillips-Fein on Monday, March 4th at 6:30pm at the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Library on 5th Avenue at 40th Street.

[MUSIC]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone. Is it possible that we're learning some of the wrong lessons about American culture from the pandemic? In a New York Times op-ed, NYU sociologist Eric Klinenberg writes that people tend to talk about an epidemic of loneliness that the pandemic spawned. Klinenberg says it's really a loss of trust we should be talking about.

That theory is part of a new book by Klinenberg called 2020: One City, Seven People, and the Year Everything Changed. The city is New York. We'll hear about some of the seven people and talk about what changed that we should still be talking about in 2024, trust and other things. Yes, 2020, the year that brought an economic crash precipitated by COVID-19, 2020, the year George Floyd was murdered by a police officer, 2020, the year that President Biden first went head-to-head with Donald Trump.

Eric Klinenberg is also director of the Institute for Public Knowledge at NYU. Again, the book title is 2020: One City, Seven People, and the Year Everything Changed. Eric, thanks for coming on. Welcome back to WNYC.

Eric Klinenberg: Thank you. It's nice to be here.

Brian Lehrer: I want to start, even though this is so personal, obviously, to so many people who are in grief and everything else since 2020, still, I want to start on an abstraction, I guess, with your theory of crisis and what we can learn from it. You write, "Extreme events can make visible a range of conditions that are always present but difficult to perceive." Talk about that theory of crisis.

Eric Klinenberg: Well, it's the theory that has motivated my work for several decades now. It's the idea that crises reveal things, who we are, what we value, whose lives matter, and of course, whose don't. When 2020 started, knowing this, my first very human impulse was to socially distance, to close the door, to take care of myself and my family, but I also knew we were living through something that would be historic.

I didn't know how big and how long it would last, but I knew it was consequential, and so I just started to look at as much as I could. In fact, I think we have to look closely at what we experienced in 2020 because we're still living in this kind of long COVID as a social disease, and if we repress it, that doesn't mean it's not acting out on us.

Brian Lehrer: You refer to a French sociologist's theory of anomie, the phenomenon in which spikes in destructive behavior occur during times of crisis. Why is anomie a fitting descriptive for the state of our country in 2024?

Eric Klinenberg: Well, here we are feeling atomized, feeling on our own, feeling distrustful. We have become even more skeptical of core institutions, including government, than we were in 2020. That is saying something because that was not the happiest time even before the pandemic started. One thing that we see when a society is experiencing anomie is a spike in interpersonal violence.

It's fascinating, Brian, countries around the world experienced severe lockdowns and all kinds of traumas in 2020, and actually, by comparative standards, the US hardly did lockdowns at all. It's nothing like what happened in China or Italy or Australia or France, but we got exercised and angry and we took it out on each other. In the book, I write about those viral videos of ordinary people fighting it out in grocery stores because someone was wearing a mask or someone wasn't wearing a mask. There were cases of homicide over that same issue.

The US is an outlier in the world because, in 2020, when most societies got more peaceful, we had this incredible spike in violence, and not just guns, Brian, we had a spike in reckless driving, in vehicular manslaughter. It's like we stopped taking each other and each other's well-being into account at the very moment when what we needed to survive was solidarity.

Brian Lehrer: For example, along these lines, one of the seven New Yorkers you profile is Daniel Presti, owner of a bar on Staten Island. The story as you tell it shows us how a once apolitical bar owner on Staten Island became radicalized by government mandates and a lack of support from the government. Tell us some of the Daniel Presti's story and how it fits into that theory of anomie.

Eric Klinenberg: Presti was a bar manager in a new establishment called Mac's Public House that had just opened in Staten Island at the end of 2019. It took the New York Liquor Authority, the State Liquor Authority almost nine months to get him his liquor license. He couldn't figure out why. The authority exists to make sure that these businesses can operate safely. What took so long? By the time they finally opened, it was the slow season, and then COVID happened, and they got shut down.

His original idea with his partner was to have a neighborhood establishment where people could come and just get to know each other better. It's hitting a social need that we all have, to be together face-to-face, to gather and convene. What happened over the course of the year is he felt like he kept getting shut down and had his business operations restricted. He tried to get meetings with different agencies to find out what would happen next, when he could open, and he couldn't get anywhere, and everything was falling apart in his business, had all kinds of personal effects. He got anxious about it.

At some point, Presti and his partner decided, "We're going to fall apart anyway. We might as well take a stand." They turned their bar into what they called an autonomous zone. That wound up getting the attention of Tucker Carlson, Sean Hannity, the right-wing media. Then protesters on the right, including the Proud Boys, came to Staten Island. I learned about Presti from watching videos of the scene at Staten Island. Here it was in New York City.

What I came to learn is that Presti actually is quite like millions of people across the country who found in 2020 this feeling that they were-- not that they were lonely, but that they were on their own, that there was no one really to give them the hand that they needed. Despite the stimulus checks, despite the support that we did provide, millions of people felt like they didn't have what they needed to get by. They were terrified of their future.

The reality of America in 2020 is that many political leaders on the right spoke to people like Presti. I tell his story in the book, not to advocate for him or his position, but to humanize that part of the experience, which was really important for America.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, if we have a kind of social or cultural long COVID in this country here in early 2024, as our guest Eric Klinenberg says we do, what do you think the symptoms are? Give us a call. 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. An epidemic of loneliness, an epidemic of loss of trust, what else? Or ask Eric Klinenberg a question. 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. You can even call if you're one of the seven people he profiles in his new book 2020: One City, Seven People, and the Year Everything Changed. 212-433-9692.

Now, Daniel Presti was the lead character in The New York Times op-ed that was a little adaptation from the book. That's where you laid out the theory that people like the Surgeon General of the United States, Vivek Murthy, talk about an epidemic of loneliness being the main cultural impact of the pandemic. You say, "No, it's not loneliness. It's loss of trust." Make that contrast for our listeners.

Eric Klinenberg: Well, the Surgeon General, I think, has good reason to be raising concerns about loneliness. It's clearly a serious condition that millions of Americans suffer from. That said, I don't think there's really good evidence that we're in an epidemic of loneliness. There's clearly no evidence that Americans are lonelier than ever. There was a little spike for some parts of the population in loneliness during the lockdowns, but since 2020, levels of loneliness have plummeted across the population. The problem is we're still stuck in this feeling like something is off.

I think the reason is not because we're lonely, it's because we're what I call structurally isolated. We feel like we're on our own. A number of people who I profile in my book with very different experiences, very different politics, there's a profile of someone in every borough in New York in this book, what you get is the sense that when they needed support, when they needed to turn to our core institutions for a hand, they found that they wound up getting slapped. I think a lot of Americans are living with this.

Can I just say one area in which I think this becomes really clear is, remember essential workers, remember that concept? There was a moment when it wasn't just the pandemic but the economy was in free fall. People were losing their jobs by the millions, the market was crashing. The government said to us, some workers are essential and their contributions matter, and they have to keep going to work.

By the way, those essential workers were not the finance guys, they were not the attorneys. They were the health workers, but then there were all the blue-collar workers, the clerks and the bus drivers and subway custodians and people working in agriculture business, the meat packing plants. You would think that calling someone essential would be honorific and it would come with appreciation, it would come with support, PPE or guaranteed healthcare or maybe some kind of a subsidy, a bonus, but in America, to be called essential meant to be deemed expendable.

Essentially, we threw people disproportionately Black, disproportionately Latino out into a dangerous workforce. At the moment, it looked like maybe we were going to do something wonderful to support them, like a built-up version of the banging on pots and pans at the end of the day for the healthcare workers, like maybe collectively we would do something, but instead, it's like we walked to the edge of this moral precipice, and then we just turned around and walked back and pretended like it didn't happen.

I think what so many Americans are struggling with right now, it's not actually the problem of loneliness. It's the problem of doubting whether we are collectively capable and willing to take care of each other anymore.

Brian Lehrer: Does this connect to perhaps the story of the New Yorker from the Bronx, who you profile in the book, Sophia Zayas, a 35-year-old public servant who also served as Governor Cuomo's Bronx Regional Representative? You write about Sophia's mistrust of the vaccine despite her working vaccine campaigns in the Bronx. What do we learn from her?

Eric Klinenberg: Sophia is an amazing person. She worked tirelessly through the toughest parts of the pandemic. She is from the Bronx. She lives in the neighborhood where she grew up. Her family's there. Her job was to support the governor's efforts to provide vital resources for that region during the pandemic. That meant trying to get PPE and respirators for hospitals, helping hospitals deal with dead bodies when there were too many for them to handle. It meant supporting small businesses. It also meant, as the pandemic went on, helping to get people enrolled to take the vaccine.

Sophia is from a community where there is real skepticism about vaccines because of the history of medical experimentation without consent on Black and brown people in the US. Sophia found herself in charge of organizing these mass vaccination campaigns, which, by the way, the state targeted in the Bronx out of concerns about health inequality. The notion was the Bronx got hit really hard in the early waves of the pandemic, and they wanted to make sure they got a high uptake on the vaccine, but she herself really wondered whether it was safe enough, whether we had enough evidence that it worked.

Her story is the story of someone who's trying to fight through that ambivalence and get on board. I think that's also-- Again, to be clear, my point in telling these stories is so we get a deeper understanding of this predicament that we're in right now because there are all these ways in which it's hard to make sense of the American electorate or New Yorkers today.

On so many measures, things are better. The economy's kicking again, that there are jobs that we just learned from your interview, that the city budget's not as bad as they say it is. There's all these ways in which we're back, and yet, we don't quite feel it in our bones. We act as if the crisis is worse than ever. That's what I'm trying to help us figure out.

Brian Lehrer: If you're writing about a crisis of loss of trust, Ross in Brooklyn has a theory on a piece of that. Ross, you're on WNYC with Eric Klinenberg. Hi.

Ross: Hi. Thanks for taking my call, and thank you to Eric for writing this piece. It's an important subject to keep talking about, even though I think a lot of people's first impulse is to deny this trauma that a lot of us have been through in the last few years, whether that was just the fear or healthcare workers, what they went through. I really think a lot of it comes down to the individualization of a collective problem, that this is an impossibly complex problem to navigate.

At a certain point, and especially in 2021/2022, a lot of us were told to figure out what your individual risk factors are and then navigate based on that, which is really by design impossible to do. It's exhausting and a lot of people tune out from the base problem of protecting yourself in a public health crisis, which is still going on. Thousands of people are still dying every week from COVID.

The COVID Express sites in New York, for example, run by the city government, they were brilliant, they worked very well, but they've been shut down because we're all on our own to figure out how to navigate this disease, which leads us to a place of giving up. Thank you again. I really, really appreciate just coming back to this subject, even though the pandemic isn't over, but a lot of people would like to pretend that it is, especially because it's convenient for business.

Brian Lehrer: Ross, thank you very much. Well, Eric, how much do you agree with that?

Eric Klinenberg: Very much. I want to point out a few things. First of all, we were traumatized, I think especially all of us in New York City, because during the most difficult time early in the pandemic, we were the global epicenter. The struggle here was immense, and it was frightening for many people.

I think the thing about American individualism is that while there's no doubt that we are on the extreme when we compare ourselves to other countries in this way, we didn't necessarily have to respond to a crisis in the way that we did because along with American individualism comes along tradition of American communitarianism, the stuff that Tocqueville wrote about two centuries ago.

We are also joiners. We work at the neighborhood level to take care of each other. In fact, one of the people I wrote about in the book, Nuala O'Doherty, she's a story of the rise of mutual aid networks, which proliferated in this city and in many others during the pandemic. At the grassroots, Americans did amazing things to take care of each other, but I want to point out just how badly we were led as a nation during 2020.

I think it's important since we're in a political year to point that out, there are very individualistic countries out there. I write about Australia in the book, places that they have historic levels of individualism that had a right-wing government at the beginning of 2020, that had a prime minister led by a science denier, who's skeptical about all kinds of science, and yet they took the pandemic seriously enough to work across political ideology to form these government agencies that had people on different sides led by health experts, and they coalesced to build solidarity and trust.

Australia is an amazing case because they had some skirmishes and protests about lockdowns, yes, but they also had less excess death than they did in a typical year. In 2020, fewer people died than due in a typical year in Australia, and levels of trust spiked in Australia during 2020. We were not fated to go this way. I think it's important for us to remember the chaos and disorder and dysfunction of the federal government, especially the wild messaging that came all over the place.

Right now, you can hear on the campaign trail Trump say things like, "Are you better off now than you were five years ago?" Which is not actually the way that statement is supposed to go. It's supposed to be four years ago because there's no one more than Donald Trump who has such a vested interest in having us forget about what we lived through in 2020. Think of it as an aberration.

It's really important that we go back and remember and tell the stories of what happened in this country. It's not just the pandemic by the way. All of these crises, the economic crisis, the fights around racial justice and police brutality, the assault on democracy. This was a major year in our personal lives and in the life of our city. We shouldn't go on without stopping to have conversations about what we went through, how it changed us, and why it matters.

Brian Lehrer: It's interesting that Nuala O'Doherty comes up in your book and that you profiled her. I don't know if you know, but for our listeners, for whom that name might sound familiar and like, "Where did I just hear that name before," we just gave Nuala O'Doherty the Lehrer Prize for Community Well-Being, we call it, something we bestow on this show every year to a few people doing good work that enhances community well-being. We gave it to her for her work at the Jackson Heights Immigrant Center with asylum seekers knowing nothing about your book. What a coincidence.

Eric Klinenberg: Let me just say, this is an amazing thing that happened in 2020. We can tell the horror stories, but we built in 2020 in every neighborhood of the city this invisible civic infrastructure through mutual aid networks that came up as grassroots efforts to help people get food or to get medication or to navigate a complex health problem. The Jackson Heights Immigration Center that you just gave this award to four years ago was the COVID Care Neighborhood Network. Literally, the basement of Nuala's apartment began its transformation from a private basement into a community resource during COVID.

The same set of people who helped their neighbors get through the worst part of this crisis, they're now helping their new neighbors, the new migrants to New York City, file their paperwork for asylum so that they can start the path towards becoming American. It's important for us to remember that part of the story because some amazing and inspiring things happened in the city and in this country in 2020. That's part of our legacy too.

Brian Lehrer: Yes. We just told that story on the air of how the COVID Care Center started in her basement, and then she transitioned it to the immigrant center when the pandemic started fading and the asylum seekers started arriving. Let me just raise a question about one premise here, that the government left us on our own. There's this whole other narrative that says the government stepped up during the pandemic in a way that they're now stepping away from, but that a lot of progressives especially wish would've become permanent.

There was the expanded Child Tax Credit that cut child poverty in this country by 50% according to some studies. That's now expired. There were the pandemic stimulus checks that allowed people to stay home from work and not fall into poverty. When they couldn't go to their jobs and get their usual paychecks, there was an eviction moratorium. The government mailed free COVID tests to anybody who wanted them. A lot of the pushback on the right was the government is doing too much to support people and libertarian economics should flourish again.

Eric Klinenberg: Yes, that's an important part of the story. It's also part of the story of 2020. Not everyone was on their own. Of course, the government delivered a tremendous amount of support through the stimulus checks. We know that they didn't go out evenly or equitably. Presti's story is important because it's about the struggle of a small business to compete with the Cheesecake factories of the world.

You all remember that major corporations were able to use their highly professional expert policy lobbying staff to seize more government money than the small businesses were able to. Millions of people slipped through the cracks in the stimulus debate. The Child Poverty Reduction Act is one of the extraordinary accomplishments of that 2020/2021 moment. We did reduce child poverty by record numbers.

I think part of the reason that so many Americans feel discarded and distrustful today is because we turned our back on all those people we supported. We refuse to, and we shouldn't say we, it's the right to turn down the chance to extend the Child Poverty Reduction Act, turn down the chance to rebuild our infrastructure on a massive scale by preparing us for the next set of threats. It feels, again, as if we started this thing, we made gestures towards creating some new and better world, a new and better more secure nation, and then we stomped it out and went back to things as they were before.

I think all of that is in the air. Here we are, Brian, again. It's 2024, we're facing the same political choice that we had in 2020. We're fighting out over these same things. My fear is that because we have refused to talk seriously about what happened to us in 2020, about what was made available in terms of social protection and what wasn't, we've opened the gates for all of these revisionist histories in which people make wild claims about what this country went through.

Brian Lehrer: Tiffany in Bayonne, you're on WNYC with NYU sociology professor Eric Klinenberg, author now of 2020: One City, Seven People, and the Year Everything Changed. Hi, Tiffany.

Tiffany: Hi there. Thanks so much for taking my call, and thank you, Eric, for this important work that you've done. Going back to your point about some of the hostilities and horrific things that have happened over COVID, I was a solo female traveler. I drove from New Jersey to Michigan for a wedding. On my way back through Pennsylvania, I was in a Prius with California plates, and I stopped at a rest stop that was also a truck stop. I masked up. I was the only one with a mask.

As I was walking up to the building, a man with right-wing clothing on had a holster on. He unbuckled his holster and sprayed me with a Novocaine spray, and I ended up becoming very numb all up into my one side of my body and ended up pulling over and calling 911 and being rushed to a hospital. They theorized that he targeted me because I was the only one in a mask, and I was a lone female, and I was driving a California Prius, and he just possibly made assumptions around that, and also potentially was going to follow me and either rob me or worse.

The hospital staff in rural Pennsylvania suddenly just released me in the middle of nowhere. I had no family. My car was 15 miles away and they just said goodbye. Thank God someone from the wedding knew a state trooper in Pennsylvania who spent 45 minutes to come and get me and bring me to my car and make sure I was okay. These are the kinds of things that-- The police took-- they didn't get to the scene of the rest stop for two hours. It was terrifying. Maybe not, but it looked like it was politically motivated and that I was masking and this person--

Brian Lehrer: You told our screener the guy was wearing a Trump shirt. Is that right?

Tiffany: Yes, that's right. He had a Trump shirt on and cowboy boots. I don't want to stereotype, but he definitely was pro-Trump. [laughs]

Eric Klinenberg: Well, that's such a powerful story, and to talk about being alone in America and left on our own by core institutions, it really hits there. I guess, for me, you're raising a point that drives one of the chapters in the book. I try to understand how it is that this little piece of fabric that we put on our face took on the weight of all of our political frustration and ideological baggage. It's such an amazing story because very few countries had the kinds of feuds like the one you describe over masks.

Some people will remember that when the CDC came out in early April of 2020 with the new guidelines that Americans should wear masks in public because we understood that when they were worn properly, they really could protect us, Trump announced that policy in a press conference. During that announcement, he said, "The CDC wants you to wear masks. Personally, I'm not going to do it." Then it became this mandate within his administration that everyone had to not wear a mask. You bear your face because a mask is a sign of weakness and fear.

Mike Pence winds up going to the Mayo Clinic of all places and refusing to put a mask on while he's with doctors and patients. He's the only one there. Then the mask becomes a symbol for the right. The mask, I think it's important for us to acknowledge also, became a symbol for progressives and Democrats. The next thing you know, Brian changes his social media photo to Brian Lehrer in a mask. His name is Brian, #wears a mask, Lehrer.

Brian Lehrer: [chuckles] We didn't actually do that. You're describing an archetype.

Eric Klinenberg: [laughs] Hypothetically. Hypothetically. The political candidates, Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, started doing advertisements with masks on. That's all to say that the mask became a symbol for progressives also. Suddenly, when [unintelligible 00:29:22] I'm guessing some people listening remember that feeling like you're walking down the street and you're wearing a mask and you see someone without a mask or even worse in a grocery store, and you could feel like your blood boiling, all this anger about what that person's doing.

We've transformed these things that were neutral. There were health protections, medication, vaccines, masks. We've turned them into symbols of our politics and ideology, and it's very hard for us to deal with the current situation because of that.

Brian Lehrer: Tiffany, I'm so sorry that awful thing happened to you in 2022. I think it's important that you shared that story because people will maybe learn from it. Thank you for calling in. Eric, we're over time, but I want to put a punctuation mark at the end of Tiffany's story and your answer, which is that most of the callers on the board, if we were to keep going, would be saying some version of this loss of trust was Trump's fault. It didn't happen in other countries, and if we had had a normal president in 2020, you wouldn't have had to write a book today about the loss of trust in the United States over the last four years. In 30 seconds, how much do you think that's true?

Eric Klinenberg: Well, we know that Trump was responsible for an enormous share of the misinformation that circulated at the time. We know that many other nations that are like ours took 2020 as an opportunity to bond together and build solidarity and try to overcome partisan differences. They had different levels of success for the long term, but in the short term, they were able to mount a collective campaign to get through it. The very opposite of that happened here.

What we know is during crises, when we're dealing with new threats, people look to leaders to help them get through it. I think here in the United States, we look to a leader who spit out a lot of bile, and we're still paying a price for that.

Brian Lehrer: Eric Klinenberg's new book is 2020: One City, Seven People, and the Year Everything Changed. If you want to see him talk about the book in person, you can do that on Monday, March 4th, at 6:30 at the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Library on 5th Avenue at 40th Street in Manhattan. He'll be in dialogue with Columbia University history professor Kim Phillips-Fein. Again, Monday, March 4th, at 6:30 at the Niarchos Foundation Library, 5th Avenue and 40th Street in Manhattan. Eric, thanks so much for sharing it with us.

Eric Klinenberg: Thanks for having me here.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.