Housing Courts have a built-in imbalance. Unlike in criminal courts, there is no right to free counsel. As a result, while most landlords have lawyers, city data show just over a quarter of tenants and occupants facing eviction have counsel because there aren't enough free lawyers.

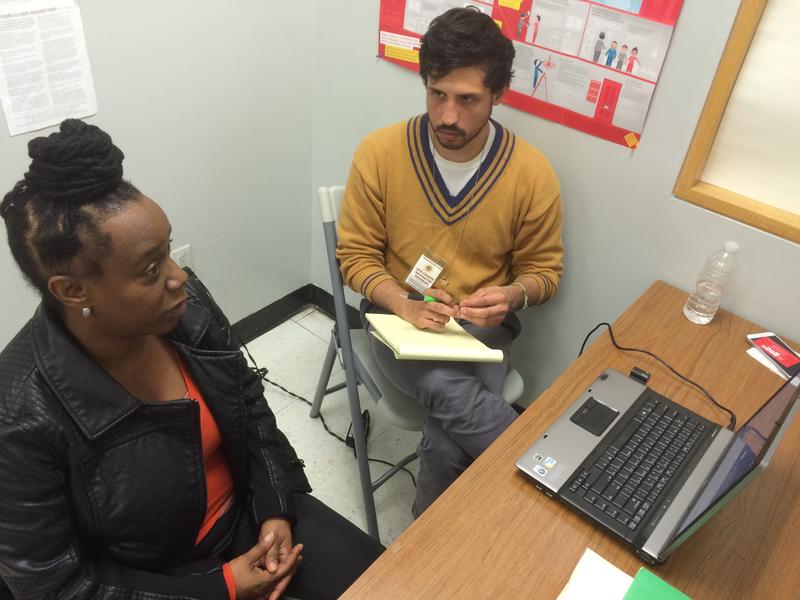

A new study by the American Bar Foundation, National Center for State Courts and supported by the Public Welfare Foundation, points to a program in Brooklyn housing court that pilots one possible solution: court navigators. These non-lawyers can't argue cases, but they are trained to help tenants fill out paperwork and understand proceedings.

The navigator pilot, which started in 2014, is run by Fern Fisher, the deputy chief administrative judge for the city's court system. She said she saw the need for more tenant assistance when she was a housing court judge in Manhattan.

"People freeze when they are in front of judges," she said. "And it’s important that the judge have all the facts before him or her, so he or she can figure out the best way to resolve the case."

There are three types of navigators working in the Brooklyn housing court pilot program; the first, and most intensive navigators, provided by the nonprofit group University Settlement, were highly successful at preventing evictions, the study found.

Normally, there is one formal eviction for every nine nonpayment cases that are filed citywide in housing courts, according to the study's co-author Rebecca Sandefur, a faculty fellow at the American Bar Foundation and an associate professor of sociology and law at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign.

By contrast, among about 150 cases that the University Settlement navigators served in the first year, Sandefur said there were no evictions.

"There were a handful of people, fewer than five, who left the apartment," she explained. "But they left voluntarily and they didn’t experience a period of homelessness — because that’s one thing you’re trying to prevent."

Teresa Anderson kept her apartment with help from University Settlement navigators. The 46-year-old single mother lost her job after getting sick in 2007 and suffering black-outs. She then had trouble paying the rent, about $800 a month, on her one-bedroom apartment in Brownsville. She said she would borrow money and get sued for eviction many times over the next few years, but never qualified for a free attorney.

Then, she met a navigator who helped her get a grant to cover her back rent. The navigator also found a pro bono lawyer who could keep the case going until Anderson got disability payments and a section eight housing voucher to help her pay the rent going forward. Eventually, Anderson prevailed and was able to keep her apartment.

"She fought for me when I gave up fighting," she said of her former navigator, who joined her in court for every appearance and paid for her car service. "It’s kind of emotional, because in the years that we did work together, I’ve never seen anybody go that hard for me."

The new study found two other types of navigators were also effective. The group Housing Court Answers has navigators helping tenants on their first day in court, when they fill out complicated documents in which they are asked to explain why they did not pay their rent. These tenants were almost twice as likely as unassisted tenants to have their defenses recognized and addressed by the court; for example, judges ordered landlords to make needed repairs for them about 50 percent more often.

A third group of volunteer navigators, known as Access to Justice Navigators, helped tenants understand different proceedings on their first day in court. The study found tenants thought the program was helpful because they were able to tell their side of the story to the court.

The entire navigator pilot program is funded through the end of 2017 with $228,000 from the city and the New York Community Trust. This goes toward three full-time navigators, plus the salaries of a few other staffers and operations at Housing Court Answers and University Settlement. Judge Fisher said she hopes the city will expand it to the other housing courts.

Some attorneys for landlords, however, question the effort. The City Council is also considering legislation that would guarantee lawyers for low-income tenants facing eviction in housing court. One lawyer, who did not want to be identified, said the city should help more landlords get their rents paid, while developing and building more low- and moderate-income housing.

But proponents of the navigators said they do help landlords by figuring out ways to help tenants pay their rent. And though they can't replace lawyers completely, Sandefur said navigators could be used more often as a less costly alternative, adding, "They’re both parts of a solution to a very big problem."