The Life and Death of Artist Michael Stewart

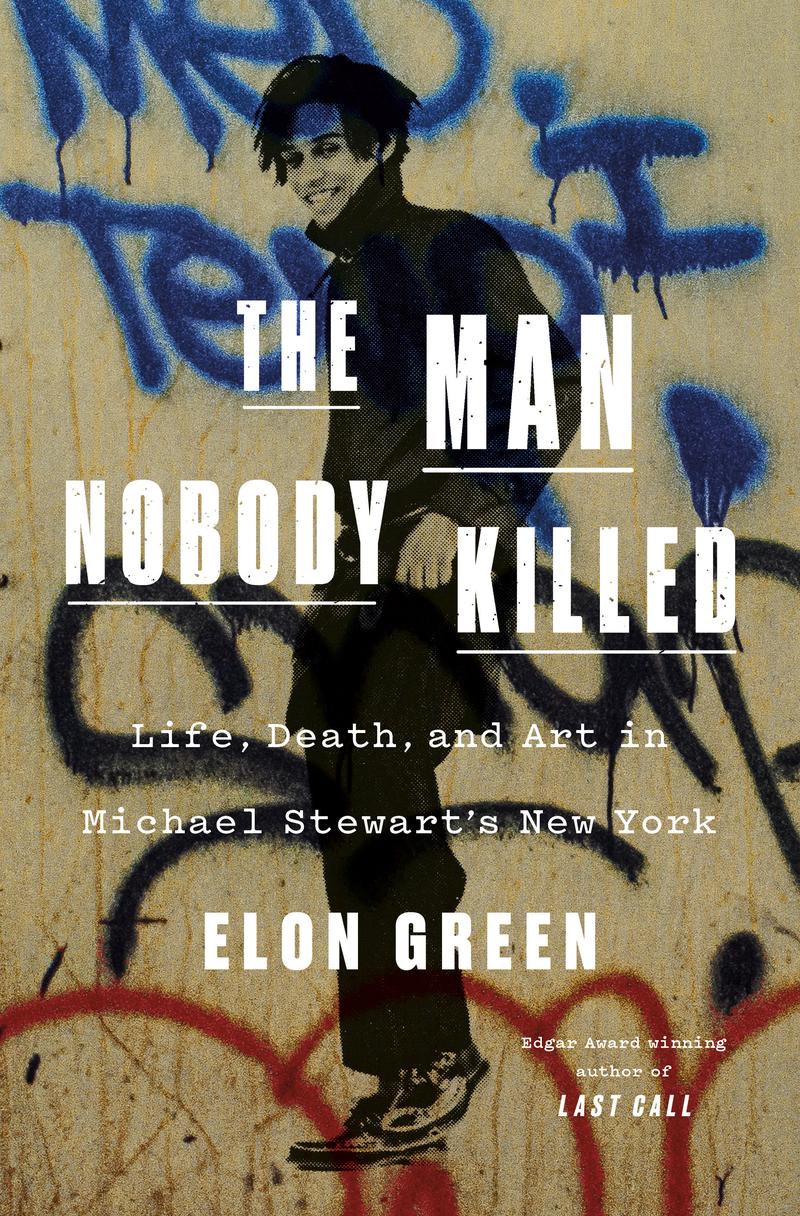

( Courtesy of Celadon Books )

In 1983, artist and DJ Michael Stewart was beaten and choked by New York City Transit Authority police after allegedly spray painting in the 14th Street subway station. After 13 days in a coma, he died in Bellevue Hospital. The new book from writer Elon Green seeks to share more about Stewart's life in New York, and explores the aftermath of his brutal death. The book is called The Man Nobody Killed: Life, Death, and Art in Michael Stewart's New York.

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. If you missed any of our segments this week, like the science behind better sleep with scientist Lynne Peeples, our conversation about music production with vocalist and producer Paula Cole, or our week-long discussion about COVID's effects on how we live, you can listen to any of those on our podcast, available on your podcast platform of choice. If you like what you hear, leave us a nice rating.

Now, let's get back into this conversation. On September 15th, 1983, in the early hours of the morning, the aspiring artist, model, and DJ Michael Stewart was arrested. Allegedly, he had been tagging a wall in a subway station. Michael was beaten by police officers from the New York City Transit Authority. He was handcuffed. His cries for help could be heard by Parsons students in a nearby dorm room. By the time he was brought to Bellevue Hospital, he was in critical condition. 13 days later, Michael Stewart died.

His death sent shock waves throughout the tight-knit creative community in the East Village where Michael worked and spent a lot of time. Artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring created emotional work inspired by his death, and a community activist demanded answers and accountability. Author Elon Green tells the story of Michael Stewart's life, death, and the subsequent trials and investigations in a new book titled The Man Nobody Killed: Life, Death, and Art of Michael Stewart's New York.

Elon Green will be speaking with David Grann at the Upper West Side Barnes & Noble next Thursday, March 20th, but he joins me now in studio. It is nice to talk to you.

Elon Green: Likewise. Thanks for having me.

Alison Stewart: I like your hat. It says writer. It's so good that you have a hat on that says writer. What was your research process like for this book?

Elon Green: It began with just reading every single newspaper account I could find. From there, it was trying to find every single living witness, attorney, friend, loved one of Michael Stewart, basically anybody who could shed a real firsthand account on what had happened.

Alison Stewart: Who was it really important for you to talk to?

Elon Green: It would have been very important to talk to the family, although I never got to. Shedding light on Michael's life in New York was, for me, the primary goal. That meant talking to staff at the Pyramid Club. It meant talking to disc jockeys at the Pratt Institute, basically anybody who was occupying the same space as Michael when he would go into New York.

Alison Stewart: Yes, that was an interesting part of the book, is you really have to understand what the East Village was like in the '80s, right? You explained a little bit, but how did you develop that atmosphere, letting the listener know what it was like to be a 20-something in the '80s in the East Village?

Elon Green: Luckily, a lot of that is very well documented, either in memoirs or biographies of people like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring. People also have vivid memories of the time and of the place. I could ask people what Alphabet City was like or what the interior of the Pyramid was like.

Alison Stewart: You could ask me. [laughs] Let's talk a little bit about the East Village artists and creatives who are all very close-knit. How would you describe Michael Stewart's role in this community?

Elon Green: I don't ever want to overstate his role in the East Village. As I said, he worked at the Pyramid. I think he was there for six months. Even though he wasn't at the level of a Basquiat or a Haring, he was visible, both because of where he worked, but also because of how he looked. Not to belabor the point, but he was gorgeous. He's tall, slender.

Alison Stewart: Just a beautiful face.

Elon Green: Yes. He also had a personality, a demeanor that stuck out.

Alison Stewart: How? How so?

Elon Green: Because he was quiet and sensitive and he didn't talk unless it was necessary, and that was not the way. Like a lot of people in that world, if they weren't established artists, that he was aspiring. He did some modeling and he appeared in Madonna's first music video. One of the things that I've always been struck by about him is that regardless of whether there was a real talent for painting, this was someone who had the capacity to ingratiate himself with some of the most remarkable people of the era. There's something very special about that.

Alison Stewart: It's interesting during this time when you think about what graffiti artists were like, the way they were treated. Why was graffiti art so heavily policed during this period?

Elon Green: That's a good question. I think it was because the powers that be, whether it was John Lindsay or Ed Koch, felt that it was tarnishing a beautiful city, which maybe to a certain extent that was true, but also the city had much larger problems. It was an aftermath of a fiscal crisis and basically nothing was funded. The fact that there might be some tags on a subway train didn't make much of a difference.

Alison Stewart: My guest, Elon Green, we're discussing his new book, The Man Nobody Killed: Life, Death, and Art in Michael Stewart's New York. Would you explain The Man Nobody Killed, the title of your book?

Elon Green: Yes. I should say first, that is also the title of a wonderful work of art by David Hammons, who was an artist in the East Village, still is an artist. It comes from an editorial that ran in the East Village Eye, a great neighborhood publication. In the aftermath of the acquittal, they ran this piece with that title to talk about how essentially there was nobody who was taking responsibility. For me, that immediately became the title because it symbolized the lack of accountability at every level from the governor's office on down.

Alison Stewart: Let's start at the beginning. Michael's in the subway, he's arrested, and then there are these conflicting accounts of what happened next. Based on your research, what happened to him when he reached street level?

Elon Green: I think what happened to him is more or less what the witnesses say happened. I think that he tried to get away. I mean, he tried to flee, which for understandable reasons, there were 11 transit police surrounding him, all for the crime of possibly tagging a subway station. I think he accidentally bumps into one of the police, and this sets off something that I don't think you can describe as anything other than an assault. I don't think we'll ever know who did what, but one way or another, he ends up in the back of an emergency services vehicle comatose.

Alison Stewart: Now, these officers were from the Transit Authority Police Department. It is now a division of the NYPD, but at the time, that was a separate policing group. How did the Transit Authority Police, how did they differ from the NYPD at this time in 1983?

Elon Green: They were basically the red-headed stepchild of the system. They made the same amount of money as the city cops, but they had inferior equipment. They patrolled solo as opposed to with partners. Also, very few people actually wanted to be transit police. Usually what ended up happening is that you would apply to the NYPD, and if you didn't get in, in the case of the arresting officer, he didn't pass the psychological exam, you would get shunted off to transit.

Alison Stewart: That's what happened to the officer who ran into him?

Elon Green: That's right.

Alison Stewart: Correct?

Elon Green: Yes.

Alison Stewart: Tell us a little bit more about him.

Elon Green: His name is John Kostick. He was the arresting officer. I interviewed him. He is very unapologetic. He was a young man at the time. I think he'd been on the job for maybe a year and a half. It was a hard job. I also don't want to look at the job of being a transit police just through the eyes of 2025 and the Manhattan of 2025. It was a very difficult job. One of the people I interviewed for the book said to me, she said, "Look, I think that Michael Stewart was murdered. However, I also think that being a transit cop in Manhattan in 1983 was the hardest job you could possibly have and a terrifying one at that." I think one of the reasons why what happened to Michael Stewart happened is precisely because of that. All of these people were just on a hair trigger.

Alison Stewart: I was curious, in the beginning of the book, how many students saw or heard what was happening. At the time, did they know that a man on the street saying, "Help me, somebody help me," what was actually going on?

Elon Green: No. All of these students were from out of town. Students who lived in the freshman dorm, the Parsons freshman dorm on the west side of Union Square were not local. That meant that they had been in Manhattan for maybe two or three days at that point. Most of them had never spent any time in the city. All they knew is what they had heard, which was that it was a dangerous, crime-ridden place.

The reactions from them at the time tended to be, "Well, this is like everything else we've heard. It's not really a big deal." Some of them thought, "Well, if he's being beaten like this, he probably murdered somebody." They didn't really do much of anything. I heard stories that eventually some of them got bored and closed their windows and went back to bed.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Elon Green. We're discussing his new book, The Man Nobody Killed: Life, Death, and Art in Michael Stewart's New York. What did the police officers, what did they say happened?

Elon Green: They say that he fell of his own volition, maybe trips on the steps or trips when they're in Union Square, but they say nobody hit him, nobody kicked him, nobody used a blackjack. It was all self-inflicted. Of course, they say, "Well, he was drunk and he was on cocaine and he had a heart attack because of the excitement," all of which, with the exception of the fact that there was alcohol in his system, there is no evidence for.

Alison Stewart: Once he got to the hospital, what did the hospital staff observe about Michael Stewart's condition?

Elon Green: They immediately realized that there had been physical violence inflicted on him. Word spread immediately that there seemed to be some kind of cover-up going on. Certainly, that was the attitude of the nursing staff who would have had the greatest amount of contact with him. He arrives without a heartbeat. The heroic efforts of the ER staff, they managed to restart his heart, though he never regains consciousness.

Alison Stewart: At one point, from your research, did that idea of the thin blue line start to assemble?

Elon Green: I think that was just the way it was. I don't think that there was any kind of conscious decision to cover this up. I just think that was just the instinct. It was unusual that Internal Affairs decided not to investigate what had happened. I mean, that is a genuine cover-up. The detective who was assigned immediately to investigate was furious that Internal Affairs wouldn't investigate. Not because she thought that the police had actually beaten Michael Stewart into a coma, but because she felt they didn't and she did not want their reputations tainted in the minds of the public, and so she wanted them cleared by Internal Affairs.

Alison Stewart: A big part of the story is the chief medical examiner, Elliot Gross, who performed Michael's autopsy. Before the Michael Stewart case, what was his reputation like?

Elon Green: He never had a sterling reputation, neither worse or better than anybody else. The position of chief medical examiner of New York is pretty thankless. If you do your job well, nobody will hear about it, and if you make a mistake, everybody will hear about it.

As far as medical examiners go, he was quite high profile. When John Lennon was murdered, he did the autopsy. When Tennessee Williams died under strange circumstances, he did the autopsy for that too. Anytime there was a fairly high-profile case or a very sensitive case, he would do it.

Alison Stewart: In this case, he made inconsistencies, inconsistent statements. How did that help the case or hurt the case of Michael Stewart? How did it cause it to become more of a headline than it normally would have? I know it's a hard question.

Elon Green: What I would say is that he generally did not actually make inconsistent statements, but they were widely interpreted that way. He came out in the hours after the autopsy and issued a statement that just, frankly, he shouldn't have, which was that the cause of death was cardiac arrest, pending further study. People conveniently didn't pay attention to the pending further study part of the statement. Whatever it was, a week later when he came out with a more refined cause of death, people treated that as if it was a flip-flop, an inconsistency, when, in fact, it really was just a much closer version to what he would finally arrive at.

Now, he did, in fact, change his mind on cause of death as time went on, but his real sin, if anything, was being a poor communicator.

Alison Stewart: That's a really interesting way of putting it. I'll think about that. Our guest is Elon Green. We're discussing his new book, The Man Nobody Killed: Life, Death, and Art in Michael Stewart's New York. The criminal trial, this case, you go into his parents, his parents' lawyers, his parents' doctors who sat in on the autopsy. There's a lot in the book. You do talk about the case, the trial that happened, including one grand juror who got in the midst of things.

Elon Green: He sure did.

Alison Stewart: Would you explain what it was he did and why he did it?

Elon Green: Ronald Fields had been sitting on the grand jury, I think, for a couple of days at that point. He was pretty incensed about one of the cases where there had been a, I believe it was like a cement truck that had rolled over a car in Manhattan and had killed a family. He only learned later, after there was no indictment, that the man who was driving the cement truck had been under the influence. He felt that that had been withheld from the grand jury, and he believed that, basically, the withholding was an excuse to cover up incompetence on the part of the district attorney's office.

When Michael Stewart's case comes before the grand jury, he's already in the mindset of wanting to have as much information as possible when he wants it, so he gets a hold of press releases from the chief medical examiner's office. He goes off and takes photos of Union Square from a great height to try to get a sense of where the incident happened. He keeps doing things that get him upbraided by the judge overseeing the grand jury. He's chastised by the prosecutor and he always promises to do better and he never does. Ultimately, his indiscretions end up tanking the first round of indictments, the first much stronger round of indictments, and the district attorney has to do it all over again.

Alison Stewart: What happened to the police officers in this case?

Elon Green: They all ended up acquitted, which would not be shocking now, and it certainly wasn't back then. None of them went on to have long, distinguished careers. I think to some degree, the case probably broke them too.

Alison Stewart: The tail end of your subtitle of your book is Art in Michael Stewart's New York. You write in the book, "Michael Stewart and Jean-Michel Basquiat were both handsome Brooklyn-born Black men who wore their hair in short locks, made art, and dabbled in graffiti. For the rest of his short life, whenever the subject of Michael arose, Basquiat would say, 'It could have been me.'" How did Michael Stewart affect other artists in his peer group and in New York?

Elon Green: Really, it was about proximity. This was not a community that it had to really confront police brutality as a systemic problem. The East Village was very sheltered in that regard. When Michael was beaten, they were suddenly affected by it in a way they never had before and realized they had to band together to do something about this. With Basquiat, he immediately begins. He goes home the night that he hears about Michael and begins drawing skulls on the floor. Keith Haring eventually does a painting about Michael. George Condo does one as well while Michael is still in a coma.

I believe after Michael dies, Basquiat goes to Haring's studio and does a gorgeous painting on the wall. Everybody was activated by what had happened to him.

Alison Stewart: We got an interesting text that says, "As a kid who grew up going down Cross Bay to Rockaway every summer weekend, I didn't know about my own privilege. Michael Stewart's death made me a different person." What do you hope people learn about Michael from reading this book? What do you hope they learn beyond just the tragedy of his death?

Elon Green: That's a good question and not an easy one to answer because so much about what happened with Michael Stewart's life is-- so much of it was potential. We'll just never know what he could have become. I think he was someone with a tremendous talent in a number of areas, whether it be his interest in art or his skill as a model. He had a tremendous instinct and interest for music, really esoteric taste. I want people to take away what didn't happen to him and what wasn't allowed to happen to him. He was never allowed to become who he would have become. The larger, maybe 30,000-foot view is, I think I want people to understand both how much has changed and how much has not changed.

Alison Stewart: My guest, Elon Green, will be with David Grann at the Upper West Side Barnes & Noble next Thursday, March 20th. He'll be discussing his book, The Man Nobody Killed: Life, Death, and Art in Michael Stewart's New York. Thank you for joining us.

Elon Green: Thank you for having me.