The Queens Jazz Trail's New Digital Map

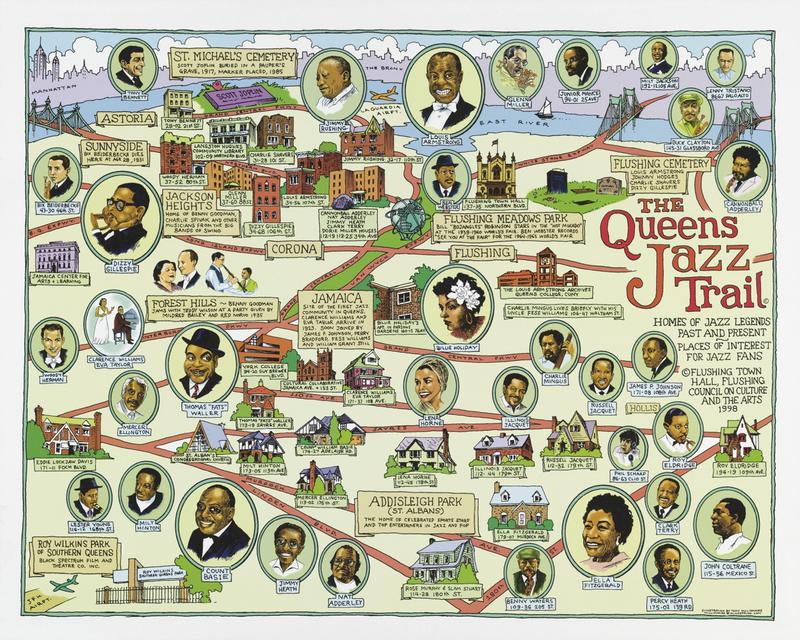

In 1998, Flushing Town Hall published the first edition of the Queens Jazz Trail Map, which documents key locations from around the borough where Jazz history was made. Now that it's been adapted into an interactive digital map, Flushing Town Hall’s jazz producer Clyde Bullard, and jazz historian and scholar Ben Young, who helped with the update, talk about recent additions, how to use the map for a self-guided walking tour, and share upcoming jazz shows and events in Queens.

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. Queens was the stopping ground for the world's most legendary names in jazz. Fats Waller and Count Basie lived around the corner from each other near Jamaica, just a few blocks away from Lena Horne and John Coltrane. Dizzy Gillespie was neighbors with Lewis Armstrong in Corona. Glenn Miller, Tony Bennett, Billie Holiday, Cannonball Adderley, Ella Fitzgerald, and Charles Mingus all once called Queen's home. Between the 1930s and '60s, many helped to desegregate some of the white neighborhoods in the borough. Back in 1998, Flushing Town Hall designed and published a map marking many of the historic jazz sites in Queens. Last year, got a bit of an update, and now there's a fully interactive digital version of the map that you can now use to plan a walking tour or simply see who might have you run into your new neighborhood. Joining me now to talk about the rich history of jazz in Queens, complete with our own soundtrack, by the way, I'd like to welcome jazz historian and scholar Ben Young. Hi, Ben.

Ben Young: Hello. Thank you, Alison.

Alison Stewart: And Clyde Bullard, who is Flushing Town Hall's jazz producer. He's been on the show before. Nice to talk to you, Clyde.

Clyde Bullard: Hello. Hey, glad to be here. You've got the best of both worlds. We have Ben Young, who's a jazz historian. I'm not a historian. I'm a producer and curator, so you got the best of both worlds from both sides.

Alison Stewart: Clyde, what about the history of the Queen jazz trail map? When and how did it come about?

Clyde Bullard: Well, according to a narrative that we were given, it all began supposedly in 1923 with Clarence Williams and his wife, Eva Taylor, who had bought a home in Jamaica, Queens, on 108th street. They supposedly bought, I think, six adjoining lots. Now, he was a producer and pianist, and entrepreneur from Louisiana. He knew Louis Armstrong. Louis Armstrong came to visit him, and he really liked the Queen's feeling because it was very rural. He eventually relocated there, and it brought attention, and many other musicians from other areas of the country started moving into Queens because it was very close to the New York music scene.

Of course, when Robert Moses designed the tribal bridge, it gave it a direct funnel right into 125th Street because Harlem at one time was burgeoning and hustling and bustling with jazz everywhere. That is the early genesis of the Queen's Jazz Trail.

Alison Stewart: Yes. Ben, when you give the scope of Queen's contributions to the jazz world, why wasn't the borough particularly recognized for those contributions? When you think about it.

Clyde Bullard: That's an interesting-- Go ahead, Ben.

Ben Young: Yes. All right. I think it's because at least partly because the work wasn't there. It was where people lived. You know that phrase, bedroom community. A lot of these cats, just like Clyde was saying, that you'd go to work in Manhattan, whether it's uptown or downtown, and then as the sun is coming up, three, four, five in the morning, whatever, you're going back to where you crash and have a family, whatever else. I think there's a lot of that in Queens in general, that it's a place where people live more than it's a place where all the action is.

No offense to the Mets, maybe [unintelligible 00:03:28] a long wave and so on, but, you know what I mean, but the performance part is different from where people [inaudible 00:03:36]

Clyde Bullard: I want to say also NEA Jazz Masters, Nat Hentorff, who was the co-creator and founder of the Village Voice, he said, "Never again should a history book be written about jazz that doesn't include the importance of Queens, because Queens is the one borough in the world that has the most amount of iconic jazz artists that once lived there.

Ben Young: Yes.

Alison Stewart: Yes. I want to get back to Clarence Williams. He was a producer. He moved to the Queen's neighborhood of Bricktown, southeast of Jamaica, in 1923. Ben, I want to ask you what Clarence saw in Queens. Why do you think this would be a good place for jazz musicians to congregate?

Ben Young: Well, I think, for starters, it was a place for him to congregate. The thing that Clarence Williams had in music probably is related to what he had as a neighbor, which is magnetism, that he was going to drop the word on his colleagues. James P. Johnson moved out a little bit later in the 20th century to take one of those spots right next to Clarence Williams. These are 100-year-old names, but they still show up in a lot of composer credits for songs that people know. The issue for Clarence Williams was he's a person who likes to make things happen in music and also a bit of a magnate.

This idea that he buys up a bunch of lots, he knows better than a lot of other people know. This city's only growing. If you make the investment now, it'll pay off for you later. Whether you get started. If things go bad, you can start a farm. If things go good, you can sell it to your friend or sell it for big money later on. Then I think with the tumble of James P. Johnson coming out with sort of this is relying a little bit on Phil Schapp's, history. Of course, he was born and raised in Queens, or grew up in Queens, at least, and saw a lot of this happening.

As he would say it, that new magnetism, plus Louis Armstrong moving there in the '40s, meant, like, wow, suddenly now you want to be there to rub elbows with people, in addition to the simplicity of it being a great good idea.

Alison Stewart: Well, here, let's hear a little bit of Clarence Williams. Here he is singing with pianist James P. Johnson. This is You Don't Understand, recorded in 1929.

[MUSIC - Clarence Williams: You Don't Understand]

It makes me grieve when you turn me away

But I know, dear, that you don't understand

My little baby, you won't believe anything that I say

I'm sorry that you don't understand

Open up your heart, let me in your heart I'm pleading.

No one else will do. Cause it's only you I need in my faith

You hope and my love's in your hand

But I know there that you don't understand

Alison Stewart: You know. An article in Queen's Clyde noted that these musicians were usually among the first Black people to live in these neighborhoods. Tell us a little bit about that. Was that difficult for them? Were they famous enough that people looked the other way? Tell us a little more.

Clyde Bullard: Well, by the time that musicians were able to afford to live in Addisleigh Park or buy homes in Queens, they were probably moderately or well known, so they could afford it. They were more than just the average African American, or Negro, as they called them at that time. People. They were celebrities. People were probably very enamored to be living near them or adjacent to them. I never heard of many problems of any racism or anything happening in Queens or Addisleigh Park.

Alison Stewart: Yes, you can see on the map where people lived and back in 1998, when it was first printed, Ben, when it first came out. Originally, tell us, what was the purpose of the map, and how were the original designers hoping people would use the map?

Clyde Bullard: Well, the purpose of the map was to illuminate and to make it known to people that might not have known, and many do not know and didn't know that Queen's was such a burgeoning place where all these jazz artists had lived, who had given so much music and happiness and joy to the world. The map was a way to document and edify that fact. It was later used to help formulate the Queen's Jazz Trail Tour, which I had presided over and administered for Flushing Town Hall for seven years.

Now, in 2004, the Queen's jazz show tour won the best jazz tour in New York City, which was really great when you think of the enormity was happening. Flushing Town Hall had partnered with a company called NYC & Company, which is not in existence anymore. NYC & Company had offices all over the world. People start their vacations where they live. They were promoting the Queen's Jazz Tour on airplanes and as well as in their offices. We were getting people that wanted to take the tour from Switzerland, Germany, Paris, London, England.

We would do the tours on Saturdays. It was $20. Flushing Town Hall at the time had a trolley. People would get on the trolley and we would take them on-- The tour was part partially on the bus, but then when we got to Addisleigh Park, people would get off the bus and be led by the tour guide, a man named Kobe Knight Boisenko. We couldn't go in the homes, actually, because you had new residents living in those homes. Milt Hinton and Mona Hinton always let the entire tour come into their home. He would graciously greet everyone and he had enough trinkets and buttons that he would give everybody.

We usually have 20,25 people, maybe 30 people. Milt Hinton was very, very gracious. Of course, he's one of the major bass players in the jazz vernacular. They called him the judge.

Alison Stewart: The judge, that's right.

Clyde Bullard: Because he was just wonderful, wonderful man.

Alison Stewart: Ben, you wanted to spotlight the song Palo Alto performed by Lee Konitz. Can you set this up? Can you tell us about the Queen's root of this song?

Ben Young: Yes, a little bit. The piano player, Lenny Tristano, we talk about now probably as much for his pedagogy as for his piano playing. He taught a whole lot of people and sort of was a 20th century guru, I guess, who had a great system for making good jazz musicians into great jazz musicians and also for starting a lot of people from scratch. He took up a residence in one of the Palo Alto's that's in Hollis. I've gotten lost myself looking for these. I believe there is a Palo Alto street that maybe is a few blocks over from the other Palo Alto.

One of your listeners probably will call in and say, I know what he's talking about. Palo Alto is obviously the name of a place in California, up near San Francisco, but when Lee Konitz recorded the tune based on his experience of being a student of Lenny Tristano and going out to Palo Alto Street, he's referring to that little spot in Hollis.

Alison Stewart: Let's hear Palo Alto.

[MUSIC - Lee Konitz: Palo Alto]

Alison Stewart: My guests are Clyde Bullard and Ben Young. We are talking about the Queen Jazz Trail map, which is now online, an interactive version available to everyone to show you how much jazz history took place in Queens. We have our soundtrack to match. All right. I read somewhere about Count Basie's "renowned pool parties." Do you know anything about them?

Clyde Bullard: I never met him, unfortunately, but our tour guide, Kobe Boisenko, or Jake Kobe Knight, he used to allegedly go into his pool. He was very gracious. He would let the children come in. He and his wife Catherine. They would let them swim there. He was well-loved in the block, and you go around the corner, two or three blocks from him, here you have Fats waller, and you go around the other way, you have Milt Hinton, and a few blocks from Milt Hinton, you have Mercer Ellington.

The area was just full of great musicians who at that time, we didn't know what indelible marks and history they would leave as far as jazz history. According to H.R.57, House of Representatives Bill 57, jazz music is the indigenous music for America.

Alison Stewart: Let's listen to--

Clyde Bullard: Very well respected and should always be preserved and probably will never die. Because the music is now ubiquitous. You can find jazz all over the world where you just think 50, 60 years ago, if you were caught playing jazz or practicing jazz in certain universities, you can almost be expelled. Now jazz has now featured, featured courses all over the world and especially America.

Alison Stewart: Let's hear another piece of music from a couple of Queens residents. Here's Count Basie and Ella Fitzgerald: Ain't Misbehavin.

[MUSIC- Count Basie and Ella Fitzgerald: Ain't Misbehavin]

No one to talk with, all by myself

No one to walk with but I'm happy on the shelf

Ain't misbehavin', I'm savin' my love for you

I know for certain the one I love

I'm through with flirtin', it's just you I'm thinkin' of

Ain't misbehavin', savin' my love for you

Alison Stewart: I have to let Ella finish there. Ben, between the 30 years, between the '30s and the '60s, how did the scene change in Queens? Because we know it's sort of. A lot of these folks either relocated or passed away, but between the '30s and '60s, what was the scene?

Ben Young: Well, that's a great question, and I have to confess, I don't go back to either of those decades expressly, but to give you a sort of view from the street. There's a difference between the sort of pioneering, actually, people study this in sociology courses, that there's a pioneering layer where somebody takes a stand, goes someplace, and then there's a real support that's indicated by the second person to take up the same mission and say, "Okay, Clark Terry is going to go out and live where Lewis Armstrong lived."

Then suddenly now somebody who was an outlier, there's a movement coming on, and this is a pretty-- There's not really a finite way of answering your question, Alison, but it's a part of that same dynamic that as soon as your friends live there and can vouch that this is a comfortable place to live and, oh, by the way, you get to sneak into Count Basie's pool parties over here, then there's enough momentum to keep it going.

In fact, in doing the revision for the latest version of the Queen's Jazz Trail map and the online edition of it, we spent a lot of time with AFM books, American Federation of Musicians, the union that employs musicians, basically just going through it, leafing through it piece by piece to look for jazz players in among all the other players. In the '60s is when you start to see this bump of a sort of new plateau of folks who either were just making it, which is true for a lot of jazz in the '60s, it was sort of starting to tail off, but there were folks who had a foothold who were able to say, I have work in the theaters or I have work in show business in some other place, or I have a job as a teacher that can supplement my jazz activity, that they were able to then become homesteaders and Queens.

You see in the '60s a very robust uptick. In other words, the thing that started as a skeleton in the '30s was just snowballing, and it's really underway by the 1960s.

Alison Stewart: The Queens Jazz Trail Map is available online. An interactive version is available for everyone to show just how much jazz history took place in Queens. My guests have been Clyde Bullard, Fuller Town Hall's jazz producer. By the way, they hold monthly jazz jams, next one being held on October 9th for all you folks who are into jazz and into Queens, and also Ben Young, jazz historian and scholar. Thank you so much for both of you for joining us.

Clyde Bullard: Thank you for having us.

Ben Young: Thanks, Alison, and check out the site.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.