NYPR Archives & Preservation

NYPR Archives & Preservation

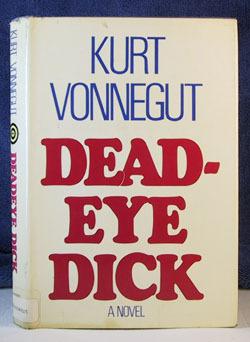

Vonnegut on Deadeye Dick, a Story of "Gun Nuts and Nukes"

Walter James Miller interviewed Kurt Vonnegut for the last time on WNYC’s Reader's Almanac on January 2, 1983. Vonnegut’s novel Deadeye Dick had just been published to mixed reviews.

As he had in several earlier conversations with Vonnegut, Miller staunchly defends his fiction against critics who continue to pan his writing as “naïve,” “unoriginal,” “unserious,” “juvenile,” “tasteless,” and worse. Vonnegut laughs off the criticism, mostly, comparing his detractors “circus geeks” who “bite the heads off chickens [his novels] for the amusement of the rubes [readers of “serious” book reviews] who walk by.”

This ongoing battle between Vonnegut and the critics in the 1980s is especially interesting given the fact that he was right in the middle of his greatest post-Slaughterhouse-Five period of productivity. Jailbird, a fascinating novel about the Watergate political scandal that brought down President Nixon, had preceded Deadeye Dick, and soon to follow were two even better books, Galapagos and Bluebeard. So while Vonnegut had been deeply stung by the harsh, and somewhat deserved, excoriation he got following the publication of Slapstick in the mid-1970s, he’s clearly past all that in this interview and enjoying his literary renaissance—even if some reviewers still are calling his novels sub-literary.

Deadeye Dick is a tragic tale of “gun nuts and nukes,” Vonnegut tells Miller. Rudy Waltz, the protagonist, while playing around as a child in his father’s upstairs gun room, fires off a round from a high-powered rifle and accidentally kills a pregnant woman as she vacuums her apartment several blocks away. In typical Vonnegutesque black humor, it’s Mother’s Day. Soon the police track down the source of the shot and drag Rudy to the station, where they utterly humiliate him and his distraught father. Vonnegut reveals the autobiographical parallels of the novel, saying that like Rudy he once “let off a high-powered shell over Indianapolis.” He then jokes with Miller that “and I’m not about to check in the newspaper files to see if anybody got shot back then.” Rudy’s father’s humiliation by the police parallels Vonnegut’s father’s emotional collapse during the Great Depression, when he lost his prestigious architectural career. The other significant tie to real life in the novel, the Reagan-era tensions with the Soviet Union over Reagan’s buildup of nuclear arms, serves to drive home Vonnegut’s warning that mankind, on both the micro and macro scales, seems absurdly ready to destroy itself with its own ingenious weapons.

Miller praises Vonnegut’s method of “telling the story in bursts,” a la Slaughterhouse-Five; his use of “playlets” as Rudy (who, like Vonnegut, tries play writing with humiliating results) relates several important incidents in his life; his inclusion of at least a dozen recipes to counterbalance the general misery of the rest of the novel; and his insight that life “is like a literary plot—with an epilogue.” Vonnegut considered his own life and work after Slaughterhouse-Five an epilogue, but this interview suggests that it was a fine one, a genuinely worthwhile second act.

___________________________

Special thanks to Mary Hume, Donald Farber and Ana Maria Allessi at Harper Collins for making the release of these broadcasts possible.

Walter James Miller was affiliated with the NYU Program in Liberal Studies.