NYPR Archives & Preservation

NYPR Archives & Preservation

WNYC: The Station That Dodged Bullets

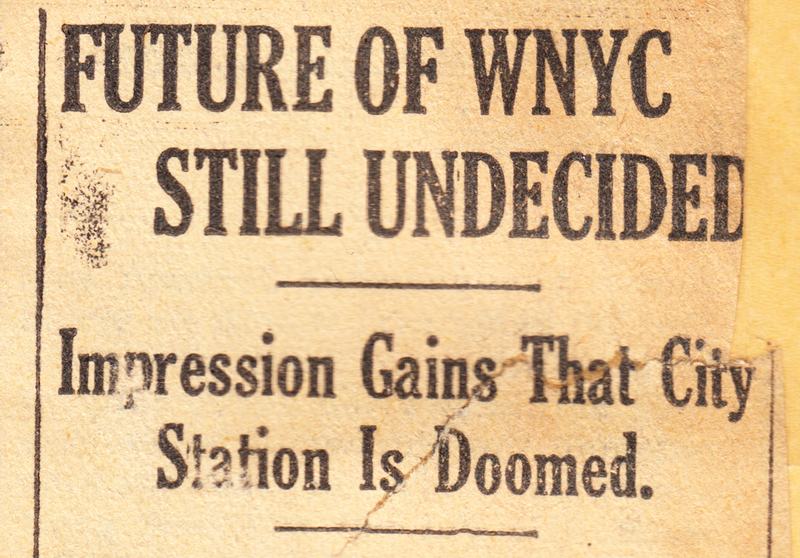

By most measures, WNYC should not exist. You might even call it a radio station with more than nine lives. Powerful forces fought to keep it from ever going on air.[1] And once it did, competitors, taxpayers, and politicians lobbied to pull its plug. The arguments were like markers on Fortune's wheel: 'Save the taxpayers money!'; 'Government shouldn’t be in the broadcasting business!'; 'The Mayor is abusing the airwaves!' (which he sometimes did), and 'New York City doesn’t need another radio station!'. Every year, especially around election campaigns and budget time, the critics, the number crunchers, the fiscal watchdogs, and the bean counters would write letters to the editor, speak out at public hearings and make calls to the Mayor, their alderman and council members. It was a perennial chorus of ‘Shut it down.’

WNYC was a government radio station in a country that didn’t have state broadcasters or believe in them. It was a non-commercial station in a broadcast system driven and dominated by commercial interests. Even among non-commercial stations, WNYC was the odd man out. It wasn’t a college or university ‘educational’ station, nor was it a neighborhood or community non-profit. By nearly every measure of what an American broadcaster should be, WNYC could not have been more out of sync. Still, its advocates somehow managed to muster just enough leverage, determination, and luck, to keep the plug in the socket and ‘The Voice of New York’ on the air for 73 years as a municipally owned and operated station.

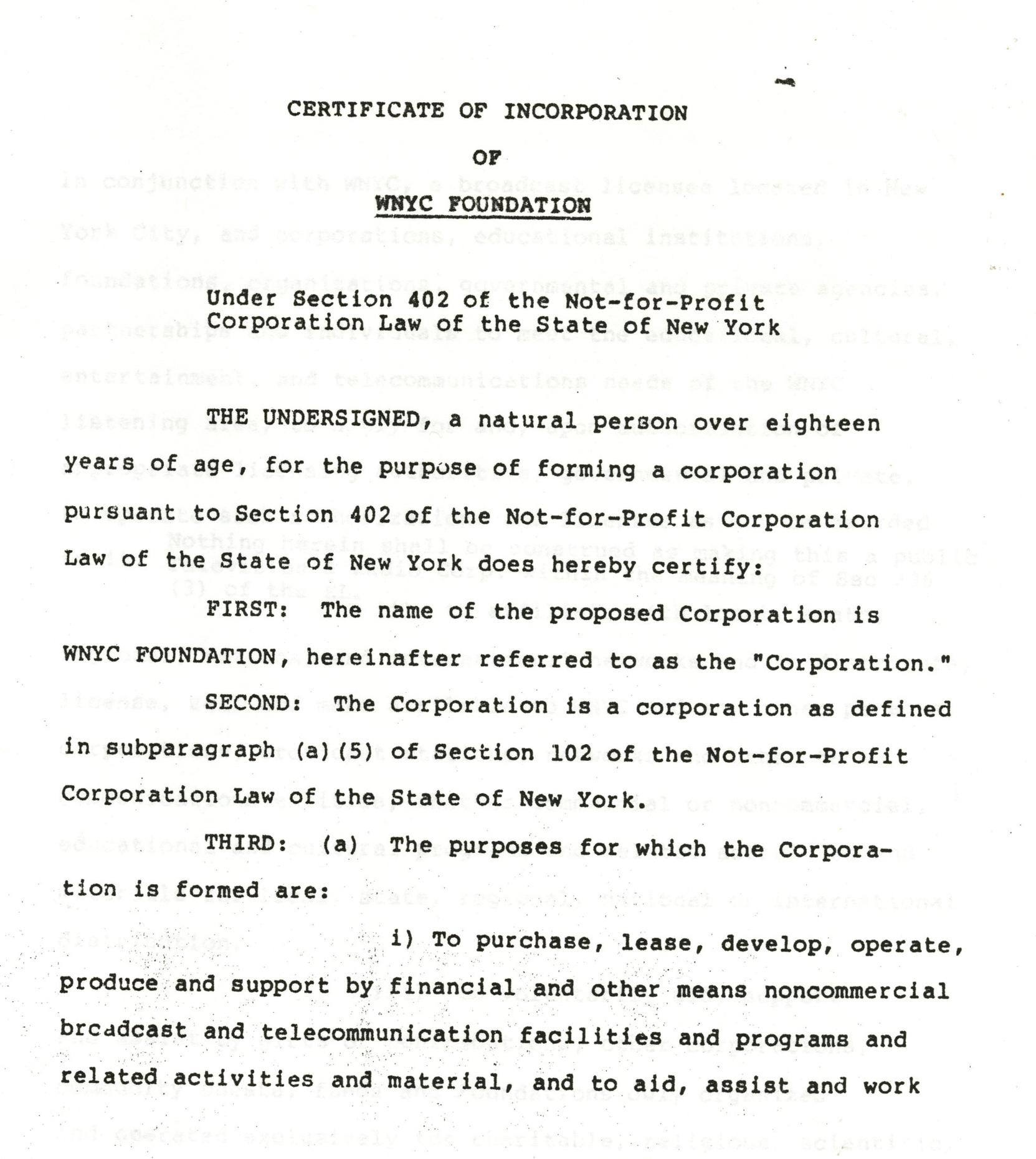

New York City's mayors were not always on board with WNYC. Fiorello H. La Guardia, in particular, was a major critic long before he became its champion.[2] The final mayoral threat, however, came in 1994 from then-Mayor Rudolph Giuliani. Fortunately, rather than eliminating the station, the former U.S. Attorney was receptive to negotiating a plan for keeping the AM and FM stations on the air as public media. WNYC-TV, Channel 31, was sold commercially. But the salvation for radio did not happen overnight. It grew out of a process that had begun 15 years earlier, in 1979, by establishing the non-profit WNYC Foundation. Launched in the wake of a fiscally troubled decade for New York, the foundation allowed the station to slowly wean itself from the City by permitting it to accept private foundation and government grants and listener dollars outside of the City's coffers.[3]

With this new revenue stream, the station grew its critical support base by developing innovative programming that included: the Peabody-awarded children's show Kids America; a storytelling festival; Senior Edition; the women's issues program Speaking for Ourselves; On the Media; and expanded remote concert broadcasts. Emphasized too were 20th century composers and artists with shows like Newsounds, New, Old and Unexpected, Spinning on Air, Airworks, and Meet the Composer. Expanded programming from National Public Radio and the addition of content from sprouting public radio outlets also bolstered listenership.[4] Had the City of New York sold the broadcast licenses before these advances, WNYC may not have survived as a public station. Those additional supportive years following the foundation's creation, under the public media-sympathetic mayoralties of Ed Koch and David Dinkins, put the station in a position that made independence possible.

I would be remiss if I didn't mention, too, that the intimacy of the medium and people (locally and nationally through NPR) dedicated to its art, rather than its commerce, were also significant factors in WNYC's survival and reinvigorating its brand. Hosts like Tim Page, Steve Post, John Schaefer, Leonard Lopate, Margaret Juntwait, Brian Lehrer, David Garland, and Sara Fishko highlighted WNYC as one of the few places on the dial that wasn't trying to sell its listeners to advertisers. Instead, they underscored the station's mission to provide engaging and essential information, with a wide variety of music (although largely classical). All of it was held together with familiar voices in your ear and keen writing for the mind's eye.

It may be hard to remember when, other than the telephone, radio was the only disembodied voice around. The smartphone, the Internet, and their on-demand universe have radically changed the notion of ‘wireless’ in ways that have indeed ended radio as it once was. When I started, field recording was done with a cassette machine. We dubbed these tapes to quarter-inch reel-to-reel tape for editing with a grease pencil, razor blade, and splicing tape. Now, it is all done with a flash recorder, computer, software, and a mouse. WNYC has always adapted to changes in technology and many times has been at the cutting edge. Likewise, it has taken on every new platform, incorporating its content into the ever-expanding ‘meta’ juggernaut; streaming, podcasting, tweeting, tumbling, Instagramming, Snapchatting, etc. Perhaps more importantly, this adaptation responds to rapidly growing competition in a realm where the station, and a few others, were essentially the only audio game in town. The playing field has radically transformed, and listeners now decide what they want to listen to and when, leaving me to wonder how well we'll do in this brave new digital world. Indeed, the current media revolution is undoubtedly WNYC's next test to master as it journeys into its second century.

Although WNYC has a long history of meeting challenges to its existence, past threats, as outlined below, were primarily political and almost seem quaint compared to what lies ahead.

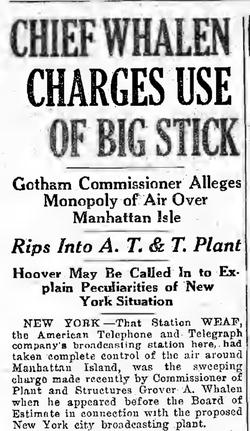

1924 March 5: NYC Commissioner of Plant and Structures Grover A. Whalen charges a conspiracy by 'the radio trust' (broadcasters, equipment manufacturers, and line leasers) in attempting to keep the city from having its radio station. WNYC went on the air July 8, 1924.

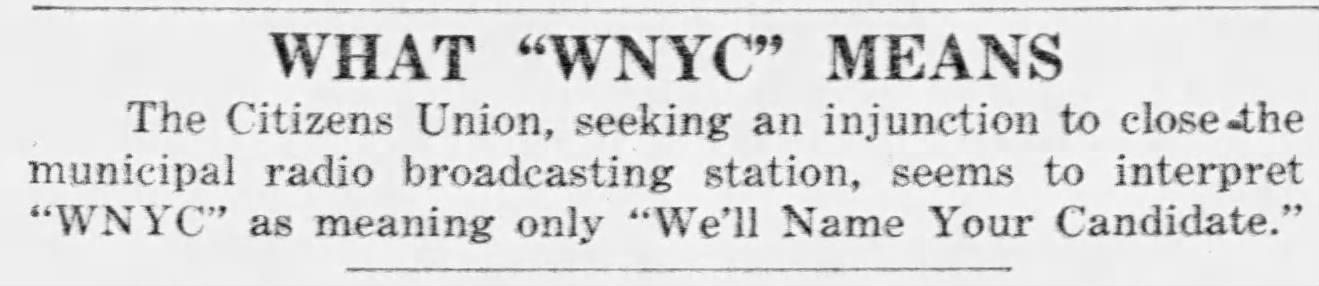

1925 August 8: The Citizen's Union files suit to shut down WNYC in light of liberties taken by Mayor Hylan to attack his opponents and use the public airwaves for his political agenda. Although the station was not shut down, the court ordered that WNYC could not be used for "broadcasting any political speeches or propaganda...for the political advantage of any official of the City of New York..." (Scher, Saul Nathaniel, Voice of the City, NYU Thesis, 1965 pg. 75).

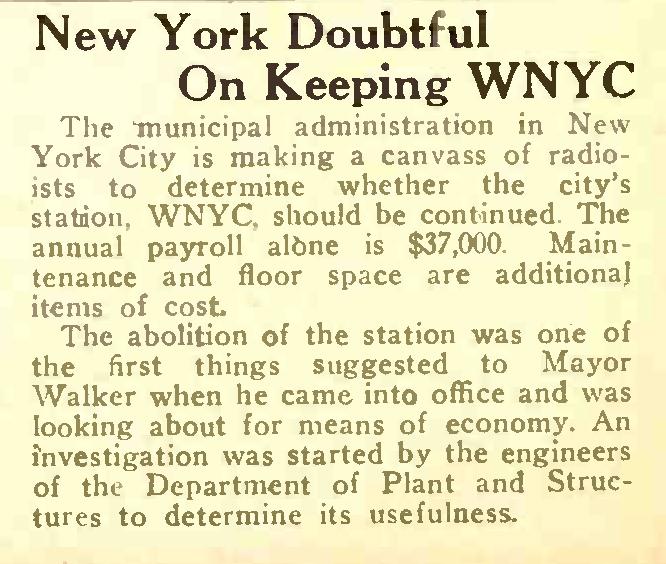

1926 March 24: The Daily News reports that "Mayor Walker is considering the advisability of conducting a poll of radio fans to decide whether or not WNYC should continue broadcasting." (pg. 111) A day earlier, the New York Post reports the Mayor had gotten "numerous requests asking that WNYC be silenced for reasons of economy, if not politics." (The Daily News, March 23, 1926, pg. 4). Walker, through Commissioner Albert Goldman, indicates that he was initially undecided about continuing the station. Goldman announces he will poll the public on the subject. A New York Times editorial the next day referring to Goldman's announcement considers the pros and cons and states: " Mayor Walker's instinctive antagonism to the station is well founded." (The New York Times, March 25, 1926, p. 22).

1927 March 12: Edgar Felix, a contributing editor of the influential Radio Broadcast magazine is noted as suggesting that WNYC should be closed down "because its program standards are hopelessly below par and will remain so unless the city appropriates a million dollars a year for talent. Furthermore the station is not being used entirely for broadcasting; its point-to-point communication is claimed a misuse of the broadcast band." Felix had represented the magazine at Federal Radio Commission (FRC) hearings and had been a Director of Public Relations at WEAF (A T & T's New York radio station and part of the original 'radio trust' fighting the launch of WNYC). He was also a consultant and promoter of commercial radio advertising. (Butman, Carl H., "Reducing Broadcasters to 300," Buffalo Evening News, March 12, 1927, pg. 2). Note: The exact quote attributed to Felix above is also found in the April 1927 edition of Radio Broadcast magazine in an extensive article on the new radio commission titled, "Welcome to the Radio Commission," pg. 557.

1927 May 28: Radio World magazine reports that WNYC is being forced by the Federal Radio Commission to share its 570 k.c. frequency. Station director Christie Bohnsack tells the publication: "We are not looking for a fight. We fully realize the problems which the control board faces. However, the City of New York is big enough to run full time on an exclusive wavelength. If not, we'll shut down. Why should the city divide time with a commercial station? We want to help the commission in every way possible but in doing so we do not want any entanglements." ("Full Time or We Quit Air, WNYC's Stand," Radio World, May 28, 1927, pg. 15).

1928 December 26: The Nation magazine charges that "municipal operation of a radio station does not mean freedom of speech, [and] in the case of station WNYC it has meant quite the opposite." The weekly charged the station with avoiding the investigation of government scandals and suppressing robust political debate. It likened the situation to England, "where government control has proved irksome and repressive." See "While We Are Distributing," The Nation, Vol. 127, no. 3312, December 26, 1928, pg. 699.

1932 October 9: Republican nominee for mayor Louis H. Pounds calls for the elimination of WNYC, "that most useless station," from the 1933 city budget. ("Leaders Await Declaration of Judge O'Brien," Long Island Daily Press, October 10, 1932, pg. 2). While the McKee administration didn't shut down WNYC, it came close to significantly cutting its staff that budget cycle.

1932 October 14: Peter Grimm, Chairman of the Citizens Budget Commission, says WNYC is a "joke" and should be abolished. ("5-Cent Fare on City Subway Held Menaced," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 15, 1932. pg. 7).

1933: Fiorello H. La Guardia campaigns for Mayor on a 10-point cost-cutting program of reforms. The abolition of WNYC is number nine on his list. (See also, Luscombe, Irving Foulds, WNYC:1922-1940--The Early History of a Twentieth-Century Urban Service, NYU Ph.D. Thesis, 1968, pg. 153).

1933 December 4: Minority leader Joseph Clark Baldwin III proposes the abolition of WNYC to the finance committee of the Board of Aldermen as part of a cost-saving package for the 1934 city budget. ("Baldwin Seeks $40 Million Cut in City Budget," The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 4, 1933, pg. 1).

1934 January: Mayor La Guardia appoints Seymour N. Siegel, assistant program director of WNYC, and sends him across the street to begin to "shut the joint down." WNYC is placed on probation while a panel of broadcasting experts assess the station's problems, pros, and cons and writes a report for the Mayor, which ultimately tells the Mayor to keep the station and implement a list of recommendations for changes and improvements, many of which were acted on. However, before the study and report are done, wolves are baying at the station's front door. Commercial broadcaster WINS telegrams the Mayor to ask the Federal Radio Commission for WNYC's airtime, CBS offers to negotiate a deal for acquiring WNYC's frequency, and the New York Post offers the city $50,000 for the broadcast license. (Scher pg. 135).

1937: December 29: In a letter to Princeton University's Dean of the University Chapel, Robert Russell Wicks, Mayor La Guardia writes: "I am glad you like the 'Master Work Hour,' Frankly, I'm not at all satisfied with what we are doing over the Municipal Radio Station. I hope soon to be able to devote some time to it and make it an outstanding station for education and art. I am so hampered by lack of funds that we actually have to beg, borrow and even steal to keep the station going. I am going to make something of it or discontinue it -- I don't want to discontinue it." (La Guardia, Fiorello H., papers August 1937- December 1937, La Guardia and Wagner Archives, Box 3198, Folder 10, Microfilm 0515).

1938 March 8: A travelogue program elicits calls for shutting down WNYC by City Council members charging WNYC with airing Soviet propaganda. An investigation into Communist influence on WNYC programming is initiated. See: Communist Propaganda or Capitalist Commercial? An attorney for the City Council committee issued a statement in August of that year announcing that the investigation would not be limited to the alleged propaganda broadcast but would be expanded to consider the station as a whole. "We hope a well-defined policy will come of the investigation if the committee does not conclude to recommend its demolition." (Carlton, Leonard, "WNYC 'Red' Probe Seems to be Doing a Corrigan," New York Evening Post, August 9, 1938, pg. 12).

1939 March 30: Bronx Borough President James W. Lyons issues one of his many calls for the abolition of WNYC. Addressing the Board of Estimate, he charges, "WNYC is of no use to the city except to give puffs to the city administration...We ought to get rid of this wind-jamming machine giving vent to the whims and policies of the city government." ("Lyons Loses Fight to Abolish WNYC," The New York Times, March 31, 1939, pg. 23) Two days later, the Bronx official took his message directly to WNYC listeners, saying that being on the station "is very much like a man in a telephone booth talking to himself." ("Lyons Over WNYC, Asks End of WNYC," The New York Times, April 3, 1939, pg. 3).

1939 April 13: The New York Journal American reports, "Elimination of such 'useless' expenditures as Municipal Radio Station WNYC and postponement of the three-platoon system in the Fire Department were demanded by the Citizens Budget Commission today as more than 1,000 objectors to the city budget besieged City Hall for the second successive day." (April 13, 1939, pg. 34)

1940 April: Influential attorney Harold Riegelman requests the Board of Estimate at its budget hearing discontinue WNYC on the grounds that New York City had ample radio coverage and that in view of the city's financial situation, WNYC's continued operation cannot be justified. Riegelman recommends the sale of the station.

1940 May 21: The Taxpayers Union, the Midtown Real Estate Association, the Association of Harlem, and Bronx Property Owners, Inc., issued a joint statement calling for the end of WNYC. The groups charged, "That the broadcasting station is an unwarranted luxury is demonstrated by the recent report of the Police Commissioner that 'serious crime' is on the increase in the city." The organizations argued, "The $118,000 now misspent by the city on broadcasts would enable the appointment of fifty additional policemen who are sadly needed at this time to prevent further crime increase." ("Would End WNYC," The New York Sun, May 22, 1940, pg. 31).

Meanwhile, Mayor La Guardia claimed the attorney for the Citizens Budget Committee against the station was also having secret meetings with CBS in Mexico to further undermine the station in its quest to remain on the air after sunset. WNYC was forced by the Federal Radio Commission to shift its frequency from 570 to 810 in 1932. Because of this, the station had to sign-off off the air at sunset to avoid interfering with the CBS clear-channel station in Minneapolis at night when AM signals travel farther. WNYC had been trying to get a special dispensation to remain on the air a few hours longer each day, a waiver they did not get until after the U.S. entered World War II. The wrangling between WNYC and WCCO, however, continued and would become the most protracted fight in FCC history.

In a May 25, 1940 letter to the FCC Mayor La Guardia wrote: "For some time The Citizens Budget Commission, Inc. through its council Harold Riegelman, has been engaged in an attempt to eliminate WNYC and turn it over to private radio interests. Only after the City Commissioner of Investigation, William B. Herlands, subpoenaed and examined two vice-presidents of Columbia Broadcasting System did we discover certain correspondence between Columbia Broadcasting System and Riegelman; and we learned that Columbia Broadcasting System and Riegelman were working in collusion in furtherance of this vicious scheme."

The Mayor called on the FCC to investigate and charged there was a conspiracy between the civic group and CBS: "The collusive arrangement between Riegelman and Columbia Broadcasting System and Riegelman was conceived and maintained in secrecy. Neither Columbia Broadcasting System, Riegelman, nor any of their employees ever disclosed to any public agency or to the public generally the fact that they had been meeting and working together on the proposition that WNYC be suppressed as a municipal broadcasting station, and that it should be turned over in the form of a lease to private interests." (La Guardia, F. H., 1940 correspondence file, La Guardia and Wagner Archives, CUNY).

Harold Riegelman later wrote of the charges: "I suspect that the City's application (for an extension of broadcasting hours) was languishing and the Mayor was eager to dramatize the matter...In May 1940, the Mayor, with a great show of heat, charged me with conspiring with a vice-president of CBS to take WNYC away from the city. The scene of the alleged conspiracy was laid in Mexico which certainly gave the charge a fine conspiratorial flavor. The tale of course a pure fabrication from first to last. I took vigorous exception to it and challenged the Mayor to present the facts to the FCC As I recall, nothing ever came of it." (Harold Riegelman letter to Milton Nobel, June 3, 1952 in Nobel's 1953 CCNY masters thesis, The Municipal Broadcasting System, pg. 64).

1941 October 23: William O'Dwyer campaigns for Mayor against Fiorello La Guardia and, among other things, suggests , the closing of WNYC if he wins. "There is a place to discuss the merits of dried fish versus fresh fish, but that place is not the city radio station, and the station shouldn't be used to put one business out of existence." O'Dwyer was critical of Francis Foley Gannon's weekday radio reports for the Department of Markets advocating fresh fish at the expense of dried fish vendors. ("O'Dwyer Assails Markets Policy," The New York Times, October 24, 1941, pg. 15).

1942 May 18: The Citizens Budget Commission recommends the finance committee of the City Council close WNYC to save the taxpayers money. (The New York Times, May 18, 1942, pg. 14.) This would occur the following year (The New York Times, May 17, 1943, pg. 17) and in 1944 as well. (The New York Times, May 13, 1944, pg. 1).

1943 May 26: Jerry Franken wrote in PM column Heard and Overheard (pg. 26):

The annual attempt to wipe the City's own station, WNYC, off the dial is underway. It goes without saying that the movement has the staunch support of the City Council's reactionary hatchetmen, but this year something new has been added—the support of so-called civic-minded businessmen. Actually, all these self-seekers are trying to do is to finagle the budget so that they might gain by reduced taxes somewhere along the line. As matters stand now, the Democrats in the Council have killed WNYC's appropriation, $106,915. Mayor La Guardia will undoubtedly use his veto power to restore the appropriation. The Democrats are shy of two votes needed to override the Mayor's veto.

Soon after, Leonard Lyons wrote in his syndicated newspaper column:

There's a split in the Democratic ranks at the City Council. The Manhattan bloc notified the rest that it would support the continuance of the municipal station, WNYC ... In the meantime, a committee of N. Y. notables, headed by H. V. Kaltenborn, Wm. Fellowes Morgan, and Walter Damrosch, will start a battle to preserve WNYC.

(Logan, Malcolm, "Budget Cut May Hit WNYC," The New York Evening Post, May 20, 1943).

1944 May: P. J. Griffin, Secretary of the Flatbush-based Family Civic League, calls for the sale of WNYC. The group petitions the Board of Estimate and City Council, arguing "members of this league do not feel that a radio station is a necessary adjunct to our city's government." ("Family League Would Give Mayor Air, Sell WNYC," The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 10, 1944, pg. 5). On May 21st the City Council adopted a Finance Committee report and votes to abolish the annual appropriation for WNYC. The measure is vetoed by Mayor La Guardia and the council fails to override. (The New York Times, May 21, 1944, pg 42).

1945 December 11: Bronx Borough President James J. Lyons calls for the sale of WNYC for $2 million. In a letter to the Board of Estimate, he argues the move would save an annual $90,180. The proposal was previously submitted in April 1945. Lyons says, "There is no more reason for a municipality to operate a broadcasting station than a newspaper." (Levin, "Heard and Overheard," PM, December 12, 1945, pg. 17).

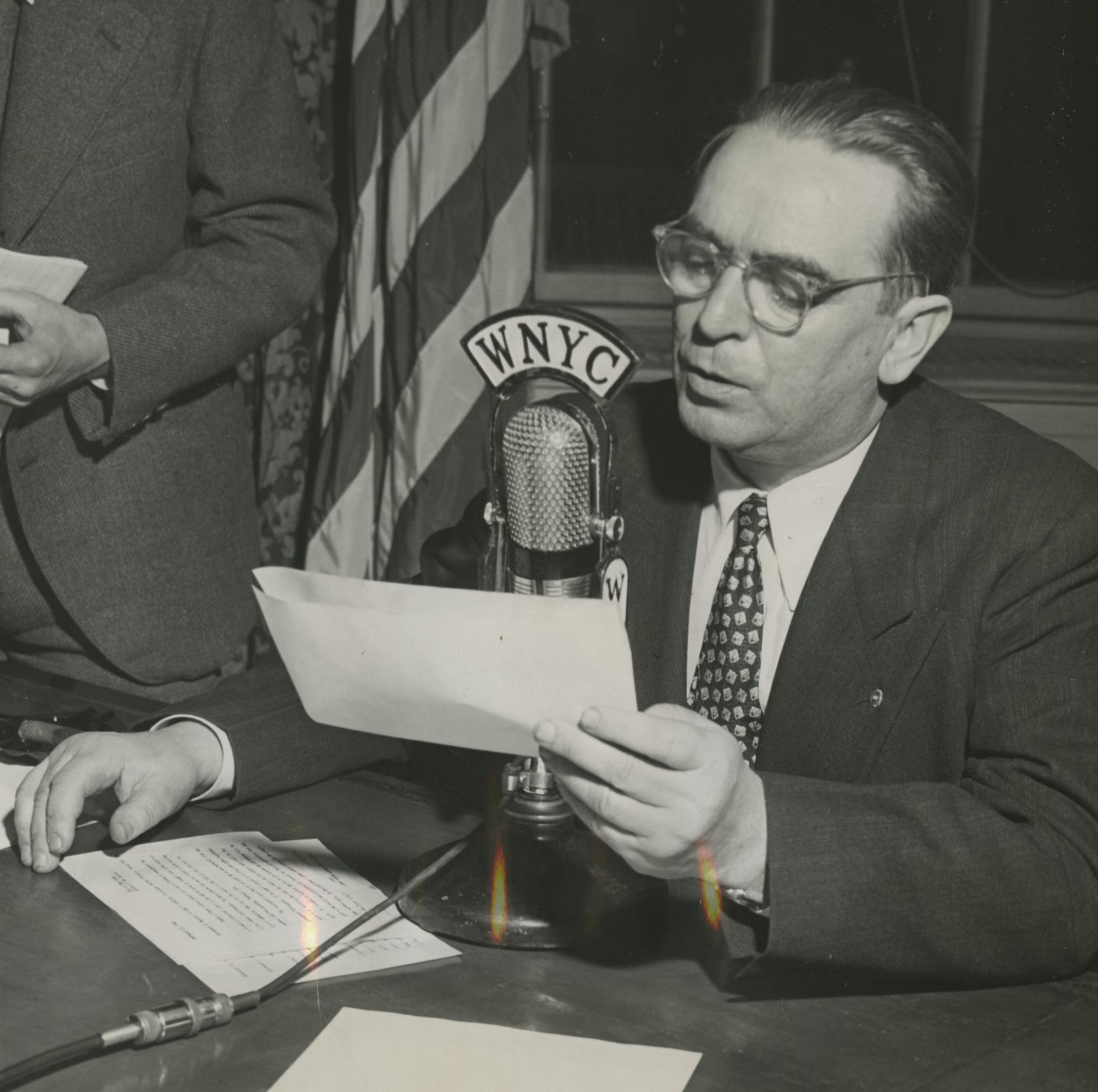

1946 February: Radio Daily reports Mayor William O'Dwyer appoints a committee to look into the issue of selling or leasing WNYC to commercial operators. In his 1965 NYU thesis, Voice of the City, Saul Nathaniel Scher writes, "Rumors were rife that the O'Dwyer Administration was indifferent to WNYC and that people close to the Mayor were suggesting the station be sold to private interests or be operated commercially by the city so that a profit could be realized on an allegedly wasteful enterprise." (Scher pg. 277) Among those pressing for a closure of the station were Commissioner of Parks, Robert Moses, several members of O'Dwyer's budget committee including Deputy Mayor George E. Spargo, and City Council Majority Leader Joseph Sharkey.

Scher also notes an unsent letter in O'Dwyer's papers indicating his mixed feelings about the station and thoughts for a trial or probationary year that never materialized. He wrote in part: "It seems to me there is no legitimate place in city government for a radio station which is the personal instrument of the Mayor and of the administration which happens to be in power. On the other hand, I can see decided benefits to our citizens from a station..." (Scher pg. 282) .

1946 August 6: Radio Daily reports a $2 million offer to purchase WNYC has been presented to the Board of Estimate by an unnamed New York City newspaper, according to James L. Lyons, Bronx Borough President. An earlier unidentified newspaper clipping from December 1, 1945, in the WNYC Scrapbooks (NYC Municipal Archives) reveals the offer came from newspaper publisher Theodore Newhouse.

1947 December 9: George Durst of Jamaica, Queens, a prescient fan of WNYC and frequent writer to New York City newspapers, suggests to a PM columnist the following:

I have a psychic hunch that radio station WNYC will cease to exist before long, now that the politicians have succeeded in getting rid of Proportional Representation in the City Council. Therefore I suggest a novel idea: To date, there is no sort of La Guardia Memorial. Well, I suggest that the many friends and admirers of the late Mayor La Guardia should create an F. H. La Guardia Memorial Foundation Fund to purchase WNYC when, as, and if the politicians try to sell the station out to private interests.

Durst argues there are enough La Guardia fans to fund the foundation. ("McManus," PM, December 9, 1947, pg. 19). The following day the Long Island Star-Journal reports that the Elmhurst Community City Council has passed a resolution calling to eliminate WNYC as part of a cost-saving measure in the city budget.

1948 November 10: The Equity Taxpayers Association votes to write Mayor O'Dwyer and the Board of Estimate calling for the sale of WNYC. The Queens-based group argues the money is sorely needed elsewhere in the city's budget. ("Equity Objects to O'Dwyer's Radio Plans," The Leader-Observer, November 18, 1948, pg. 1).

1950 November 9: The Equity Taxpayers Association of Elmhurst, Queens, opposes the addition of WNYC-TV to the Municipal Broadcasting System. The group's secretary J. J. Lantelme writes to the FCC requesting it deny WNYC's application for a television license calling it a needless expense to city taxpayers. He also praises the federal agency for denying a WNYC request to remain on later on election night to report on election returns. ("Equity Opposes City Having TV Station," The Leader-Observer, November 9, 1950, pg. 1).

1951 August 7: A group of veterans and conservative groups calls on the Mayor to stop funding WNYC's presentation of entertainers, they say, are from communist front groups. The New York Journal American reports on a letter sent to Mayor Impellitteri by Rabbi Benjamin Schultz on behalf of the "Joint Committee Against Communism." The group, according to the article by Howard Rushmore, represents the American Legion, the VFW, the Catholic War Veterans, the Disabled War Veterans "as well as borough civic and fraternal organizations." Schultz's letter was quoted, "Why should the taxpayers of the city finance the frequent appearance of entertainers linked to communist front groups?" The rabbi also called on the Mayor to investigate the situation before "a Senate subcommittee spotlights the conditions prevailing at our city-owned station."

1952 November 17: City Comptroller Lazarus Joseph proposes shutting down WNYC to save money. Mayor Impellitteri opposes the idea the following day. In addition, a storm of protest from station advocates follows, and Joseph does not raise the issue again. ("City and State Officials Haven't Agreed on Plan," The Kingston Daily Freeman, (AP Report) November 18, 1952, pg. 7).

1958 December 1: The New York City Chamber of Commerce recommends the elimination of WNYC to save $485,535 for the 1959-1960 fiscal year. ("2 Budget Experts of City and State Meet this Week," The New York Times, December 1, 1958, pg. 1).

1971 June 3: Marie La Guardia, widow of the former Mayor, and former WNYC Director Morris Novik are co-chairs of the "Save WNYC Committee." They call on Mayor Lindsay not to sacrifice the station because of the current city budget crisis. Fifty-five WNYC employees were recently laid-off. Volunteer WNYC science reporter Philip Koltar urges supporters of WNYC to write the Mayor and other city officials. ("Mrs. La Guardia Heads Campaign to Save WNYC," The Riverdale Press, June 3, 1971, pg. 3).

1972 April 22: Amsterdam News columnist Billy Rowe reports that some prominent Black community leaders talk to Mayor Lindsay about buying WNYC. (Billy Rowe's Notebook, The New York Amsterdam News, April 22, 1972, pg. A12).

1976 April 15: Mayor Beame calls for the transfer of WNYC to a nonprofit public benefit corporation. The Times wrote, "The mayor's action makes it clear that the city intends to end its 52-year involvement with noncommercial broadcasting as another step in paring its budget." A public benefit corporation would require approval through legislation from the state. Meanwhile, the city is also considering a WNET proposal to take over the stations, which a month later faces stiff opposition by a Citizens Committee headed up by former Mayor Wagner and Marie La Guardia, widow of Mayor La Guardia. (Brown, Les, "Beame Urges Transfer of City Stations' Control," The New York Times, April 16, 1976, pg. 33).

1976 September 10: Mayor Beame appoints a fiscal task force to make recommendations regarding the future of WNYC. The station's budget has been cut by one-third. He says, "The city's role in the operation of WNYC must be fully reviewed in light of our austerity program." ("Task Force Named to Aid WNYC," The New York Times, September 10, 1976, pg. 87).

1994 January 9: A committee appointed by Mayor Giuliani recommends that the city sell WNYC Radio and TV to help fill the city's expected $2.3 billion budget gap. Declaring that the city is getting "out of the broadcast business," Mayor Giuliani promises to sell the stations to the highest bidders. (Mitchell, Allison, "Mayor Given Array of Ideas on Privatizing," The New York Times, January 9, 1994, pg. 21).

1994 February: New York Newsday and New York Post both publish editorials urging Mayor Rudolph Giuliani to sell WNYC

1994 March 29: WNYC Foundation board Chair Irwin Schneiderman sends a memo to staff to disregard rumors about the station's future and keep doing a great job despite the current uncertainty.

March 21, 1995: A deal between the WNYC Foundation and the City of New York is made to sell the WNYC AM and FM licenses. WNYC-TV will be sold to a commercial buyer. See also: Going Public: The Story of WNYC's Journey to Independence.

1997 January 27: WNYC officially celebrates the sale of the AM and FM licenses to the WNYC Foundation for $20 million over six years.

________________________________________

[1] Lanset, Andy, The Man Who Fought For and Founded WNYC, May 29, 2014, wnyc.org.

[2] It took some lobbying from Seymour N. Siegel, a study and report by broadcast experts, and funding from the Works Progress Administration to change La Guardia's initially negative impression of WNYC. By 1937, there was probably no stronger advocate and his vision was that of a flagship cultural station that would lead a public radio network. See: 1937 Vision.

[3] Darrow, Peter H., Going Public: The Story of WNYC's Journey to Independence, May 10, 2018, wnyc.org

[4] NPR's Morning Edition began in 1979. American Public Radio was launched in 1983. A Prarie Home Companion began airing nationally in 1980. Monitor Radio, the broadcast service of The Christian Science Monitor began in 1984. See also The Public Broadcasting Timeline by Current.