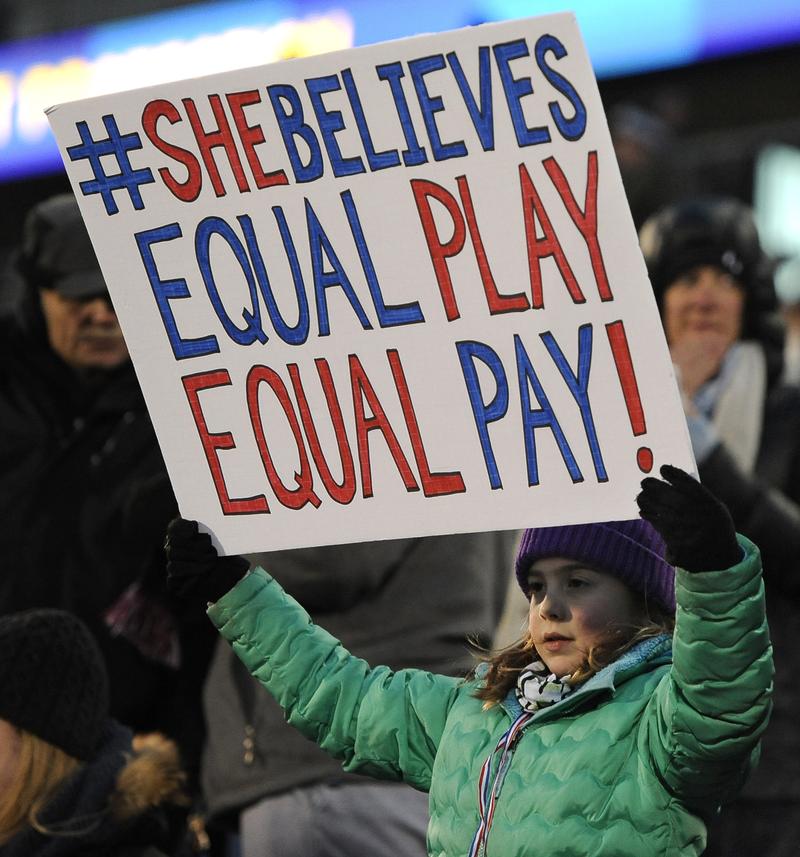

( AP Photo )

On Equal Pay Day, Josie Cox, business journalist and the author of Women Money Power: The Rise and Fall of Economic Equality (Harry N. Abram, 2024), shares the story of women who contributed to the fight for financial equality.

[MUSIC]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, again, everyone. This is Women's History Month. Today happens to be Equal Pay Day, March 12th, which is how far into this year it's been calculated that women have had to work to earn what men earned in the previous calendar year. That is, they earned it through December 31st. It took women until today to earn as much. With that as backdrop, we welcome now Josie Cox, author of a new book called Women Money Power: The Rise and Fall of Economic Equality.

Josie Cox is a journalist who has worked for major news organizations in Europe and the United States, including Reuters, The Wall Street Journal, and the Independent, where she served as business editor. She's also got an MBA from Columbia University Business School and currently teaches at Columbia in the School of Professional Studies. Again, the book is called Women Money Power: The Rise and Fall of Economic Equality. Josie, thanks for coming on, and congratulations on the book. Welcome to WNYC.

Josie Cox: Thank you so much. Thank you for having me.

Brian Lehrer: On today being Equal Pay Day, for people unfamiliar, can you say basically what it measures?

Josie Cox: Yes, exactly. Equal Pay Day is the point in the year that it takes for women to have earned the same amount of money, the average woman, I should say, in this country, as men earned the previous year. That effectively represents the gender pay gap, which is a term that is thrown around quite a lot, especially during Women's History Month. It essentially reflects the fact that the average woman in this country still only makes about 82 to 84 cents, depending on the source, on the average dollar made by every man in this country.

Brian Lehrer: Do you know roughly how much of that is because women tend to wind up in lower-paying lines of work like teaching and social work and nursing and home healthcare and how much is it that women actually get paid less for the same jobs that men also do?

Josie Cox: Definitely, yes, it's a great question, and I think the short answer is a significant amount. We have had legislation in place for decades which essentially bans men and women getting paid different amounts for doing equivalent work. Therefore, legislation has been a powerful force in erasing some of that gender pay gap. As you mentioned, there are an awful lot of cultural factors, biases, stereotypes, cultural mores, social mores that have ensured that women still dominate lower-paid jobs, jobs that tend to be more vulnerable during times of economic slowdown, during times of economic recession, and also jobs where the potential to rise through the ranks and to actually earn more are limited, so that's a really important factor to consider.

Brian Lehrer: You write about your own experience with unequal pay, including in a journalism role where you discovered you were getting paid less than some of the men you were supervising. Would you like to tell that story in a little more detail?

Josie Cox: Sure. This was a staff role that I held a few years ago. I was actually reporting on the gender pay gap at that time. It came to my attention that there was this pay discrepancy between myself and some of the men that I was managing on the team. It's so interesting to reflect on that experience now, all these years on. I think, in the moment, my initial reaction was just pure rage, quite frankly, at the managers who had made those payment decisions and those hiring decisions around me and my team.

The more I think about it and throughout the process of researching for the book and really dedicating my career as a journalist to understanding the nature of discrepancies like the one that I suffered, it's come to my attention that actually there's a much bigger picture here and there's so much more to this type of discrepancy. It's often a function of the mechanisms of the labor market, the mechanisms of capitalism, quite frankly, and just the supply and demand nature of the labor market as well. I was asked what my salary expectations were when I came into the role. I was asked what my previous salary had been when I came into the role.

What I've learned since is that these questions about the historic salaries that someone has received actually serve to perpetuate and to reinforce systemic inequalities and the fact that women tend to stay underpaid compared to men.

Brian Lehrer: Let me ask you about the subtitle of your book, The Rise and Fall of Economic Equality. Did something get better that has now gotten worse?

Josie Cox: [chuckles] It's a good question. It's interesting. I think when I first set out to write this book, I truly believed that I would be writing about a trajectory of progress. We have obviously come a really, really long way since the Second World War, which is where I really begin the reporting in this book. Women have gained the right to not get fired for getting pregnant, to not get fired for getting married, to have equal access to credit, for example, to not get paid a different amount for doing the same job as a man.

In many ways, what I realized as I started reporting was that every element of progress was met by an element of setback. I think most obviously we see that in the culture and the cultural piece that comes into this equality equation. What I'm thinking of specifically is that in the '90s, for example, when we did see more women coming into leadership, women were starting to take charge at Fortune 500 companies, for example. At the same time, we also saw an element of backlash against women coming into leadership. We saw women being judged more harshly as leaders than their male equivalents would.

At the same time, the '90s were also a time when popular culture really exploded, 24-hour TV, the internet, all these things really created this culture of sensationalism that often glorified misogyny, quite frankly, and really reinforced this idea that it's still absolutely okay to objectify women, to undermine women, and to question women's credibility in a really public way.

Brian Lehrer: Yes, you're not kind to the 1990s in the book, that's when the backsliding really began, as you tell it.

Josie Cox: Yes, absolutely. I think it's important to note that that wasn't the only time. To a lesser extent or a greater extent, throughout every single decade that I chronicle in the book, we have seen elements of progress met by real backsliding. I'm thinking of things like the Equal Rights Amendment which never passed in the '70s. Then, of course, very recently as well, the Dobbs decision when that came down in 2022, one of the arguments I make throughout the book is that reproductive rights and healthcare rights are inextricably linked to economic rights and independence.

There was this interesting arc throughout my reporting of writing about the passage of Roe v. Wade in 1973 and then a few months before I handed in the manuscript of the book, having to reexamine all of this progress that I've been reporting on as current events unfold.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, who has a story of unequal pay on this Equal Pay Day or a question for our guest Josie Cox, author of Women Money Power: The Rise and Fall of Economic Equality? 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692, call or text. Let's talk about a few points along the way in the history that you describe in the book from World War II before we get to the backsliding. One example you cite is the Equal Pay Act of 1963. Not a household law that people know. Maybe they know the Civil Rights Act of '64 or Title IX which came in the '70s, which of course you also write about. What was the Equal Pay Act of 1963?

Josie Cox: It essentially enshrined the right for women and men to earn the same amount of money for doing the same work, so it took gender into account in that decision. As you say, tremendously important for the broader story of female economic empowerment but not really recognized as such more broadly today. There were plenty of other examples of pieces of legislation that came into effect that were tremendously important, things like the Equal Credit Opportunity Act that I briefly alluded to earlier, which gave women the right to get credit and to receive credit under the same terms as men and gender to not be a factor in any decision on whether somebody should receive credit or not.

Also, things like the Women's Business Act of 1988 which essentially allowed women to get business funding. I mean, 1988, it's so recent. It's hard to believe that up until that point, a woman could still be demanded to have a male co-signer in order to get a business loan. You're right, these are all tremendous acts of progress that have to be recognized, but at the same time, I think it's our duty not to undermine the progress that was established with those particular things by neglecting to recognize the threats to progress that we're encountering today.

Brian Lehrer: What about Title IX, 1972? Many people might think of it mostly as mandating colleges, provide opportunity for women students in sports. What else is it?

Josie Cox: It's more than that. I think it's really about recognizing in educational institutions that gender should no longer be a limit to progress to potential, to the ability for women to be able to get out of an academic institution just exactly the same as what any man would be able to get out of it. Yes, I think sports is a large element of that, but there is, as you say, so much more to it and I think it's important to recognize that as well.

Brian Lehrer: Let's take what I think is a very important question and comment from Erica in Brooklyn who wants to react to even the framing of equal payday March 12th today. This is how long it took the average woman in the United States to earn as much as a man earned in calendar 2023, but that's a very general statistic. Erica in Brooklyn, you're on WNYC. Have at it.

Erica: Hi, how are you?

Josie Cox: Hi.

Brian Lehrer: Good. Thank you.

Erica: Good. I was just calling to clarify because I know based on what I've Googled, there's actually a Black Women's Equal Pay Day because Black women, in general, earn 69 cents compared to what white women earn, is 82 cents, and Hispanic women I think earn 66 cents. It's not a real true perspective on what women are earning. It's a very specific woman that's earning that 82 cents, and I just feel like that should be clarified.

Brian Lehrer: Do you happen to have it from Googling what Black Women's Equal Pay Day would be in 2024?

Erica: It's on July 9th.

Brian Lehrer: Wow. More than half the year in. Go ahead, Erica.

Erica: Exactly.

Brian Lehrer: I'm sorry, go ahead.

Erica: Oh, no. I was going to say there are other dates that I've seen in the past that were actually in August. I don't know if there's actually been improvements made, but for this year, for 2024, it's actually July 9th, and you can easily Google Black Women's Equal Pay Day 2023.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you for shouting that out. Do you deal with that in the book, Josie?

Josie Cox: I do, and I think it's such an important point, and thank you so much for raising it, Erica. I think actually metrics like the gender pay gap and equal payday, yes, of course, they are important. I think they are a decent gauge for giving a quick hit on the fact that systemic inequality still exists and is pervasive, but they're also very limited in the usefulness as metrics of actually understanding what's going on. I think they're an imperfect and crude gauge of economic equality and inequality. I think that there is a real danger in treating women as a monolithic group.

I think that by missing the nuance and by not acknowledging that the lived experience of certain women is extremely different from others, we are not doing ourselves a favor. We are doing many women a disservice. I truly appreciate, Erica, you raising that point and it is something that I address extensively in the book. I think racial divides are one thing, gender divides are one thing. There are so many other divides we also need to consider. Abilities, for example, backgrounds, socioeconomic backgrounds, religion, all kinds of things. We really need to acknowledge the multitude of those divides.

Brian Lehrer: It's one of the reasons that you focus on Shirley Chisholm as one of the characters in your book. We did a separate segment on Shirley Chisholm just recently on the show, but as a pioneer of Black People's Power and Women's Power in Congress and running for president in '72. Right?

Josie Cox: Yes, absolutely. And as a real champion of the Equal Rights Amendment as well. I consider it an absolute privilege to have had the opportunity to delve into the lives of people like Shirley Chisholm. The other person who springs to mind who I covered extensively and researched extensively for the book was Pauli Murray who is somebody who I quite frankly can't really believe that she's not a household name. She was a fantastic, amazing legal scholar born in 1910 who really became one of the first women to recognize the intersectional nature of inequality.

To really see the shortfalls of the Civil Rights Movement to the extent that it didn't recognize the women's movement and vice versa, the women's movement not fully recognizing what it could actually learn from the Civil Rights Movement. She went on to become a mentor to Ruth Bader Ginsburg. She was a lifetime friend of Eleanor Roosevelt and just an absolute remarkable champion of equality in this country. Again, just somebody who not only has been written out of history but I think in many instances wasn't really written into history in the first place. It's been a real privilege to have the opportunity to celebrate those legacies in a small but hopefully meaningful way.

Brian Lehrer: Shannon in Poughkeepsie, you are on WNYC with Josie Cox, author of Women Money Power: The Rise and Fall of Economic Equality. Hi, Shannon.

Shannon: Hi. Thank you so much for having this segment. I just wanted to share, I am 54 now, but when I was 23, I was one of the first women to venture into food distributor sales, and I went to work for one of the largest companies. After about three months, I had a female supervisor, and I think she was one of two in the country for this company. She recognized that my salary was much lower than the men coming into the role, and overnight, my salary went up $15,000 a year. This helped me when I moved to my next role to be able to advocate for more money. Thank you. I just wanted to share that. We've come a long way, but we're still not there yet.

Josie Cox: Thank you.

Brian Lehrer: Shannon, thank you very much. I'm going to go right to Holly in Brooklyn, who has a different kind of story, I think. Holly, you're on WNYC. Hi.

Holly: Hi. Thanks for having me on the call [chuckles]. I work as an art handler at a commercial gallery, and this position is an interesting sphere because it's one of labor, so I think it's a question of gender, race, and class. Anyway, I'm staff and I've noticed that for bigger projects, and I think this is across the board at other galleries, too, since it's a very physical job, they will hire freelance at the same rate as me if not more male to do the heavy lifting. This just brings in the physicality of jobs, too.

Brian Lehrer: How do you feel about that and can you do anything about it?

Holly: [chuckles] I don't know. I think for me it's just about forming a dialogue with other female art handlers has been helpful and to not really be alone in the experience, which it is a male-dominated field. It's just interesting because in this line of work, it's very physical, but we also operate in a realm of having knowledge of art. That's important but yet unrecognized in the field.

Brian Lehrer: Holly, thank you.

Holly: I don't know if you have any insight on that type of situation [chuckles].

Brian Lehrer: Do you, Josie?

Josie Cox: No, but I think it's just-- thank you, first of all, for speaking up and acknowledging this. I think you're absolutely right in certain industries and in certain very specialized roles, that is almost where we have to pay the most attention because as you say, this is something that is not widely acknowledged that this type of discrimination goes on especially in a role where you are essentially combining strength and physical ability with a really detailed and important knowledge and understanding of the industry in which you work. Thank you for bringing this to our attention.

Brian Lehrer: One more story, Sadie in Brooklyn, you're on WNYC. Hi, Sadie.

Sadie: Hi, thanks so much for having me on. How are you?

Josie Cox: Good. Thank you.

Sadie: Wonderful. I was curious about your research and just to see if something that I've noticed anecdotally in my own life and people that I've worked with plays out, but I've noticed that even in roles where specifically maybe hourly roles where it's a set hourly rate and men and women are paid exactly the same but women are being asked to take on additional tasks and additional labor that men are not asked to do.

Josie Cox: Sadie, isn't it?

Brian Lehrer: Yes.

Sadie: Yes.

Josie Cox: I think that is such an important point to raise. It actually refers back to our earlier conversation about the shortfalls of using metrics like the gender pay gap because sure, it gives us some information around pay discrepancies, but as you say, it doesn't tell us anything about unpaid labor, so to speak, that certain people are doing in the workforce that certain additional commitments, additional responsibilities that people have. The other thing that I think it raises, and it just made me think of it when you were asking your question, is that the gender pay gap doesn't take discretionary pay into account either.

Things like bonuses, things like commissions, things like special little paychecks that come around at Christmas or for any other holiday. These are things that are really discretionary, and what we know from research is that it's discretionary decisions like this that are more likely to be impacted by things like bias and heuristics that often go unchecked and that are also really hard to measure. A really important point.

Brian Lehrer: There's also the question that I think relates to Sadie's point, and Sadie, thank you for your call, about flexibility. How many more women are also doing more of the childcare and want to be able to go and pick the kids up from school and come back to the workplace? That relates to remote work and different roles as well, right?

Josie Cox: Yes. That just relates back to this cultural element that I talk about throughout the book, which is that, yes, we have made all of this legal progress. We have established all these rules, that's like the low-hanging fruits in this whole conversation about equality in the workforce, but we haven't yet managed to chip away at norms. Norms that you mention around the fact that women are more likely to be caregivers, that they are more likely to pick up the burden of childcare, which is obviously something that we saw very, very clearly during the COVID-19 pandemic when a lot of women were essentially forced to take a bit of a step out of the paid labor market and into the unpaid labor market in order to ensure that their households could keep running when schools and childcare facilities closed.

It's all of these little things. It's the fact that women are more likely to take parental leave than men. So many different things that we really have to still work so hard at in order to chip away at.

Brian Lehrer: With laws largely in place, but cultural things needing to change so much still, you write in the epilogue that we can't dismiss even the slightest hint of sexism in a throwaway comment. Then you write, polarization is the enemy of progress. In our collective quest for fairness, we must therefore always see common ground. That's a very fine line to walk. Seems to me calling out every minor sexist, slight, but doing it in a way that doesn't polarize and achieves common ground. You know what it made me think of? It made me think of this from Barbie.

America Ferrera: Always stand out and always be grateful, but never forget that the system is rigged. Find a way to acknowledge that, but also always be grateful. You have to never get old, never be rude, never show off, never be selfish, never fall down, never fail, never show fear, never get out of line.

Josie Cox: Perfectly placed. Absolutely. It's exactly that. To your point, I don't think one precludes the other. I think that we can learn to have a dialogue about something that is going on that is rooted in respect and that is rooted in compassion and that seeks to find the common ground and the common values without being afraid of speaking out against something that we think is unjust or that we think is creating some kind of setback in this common fight.

Brian Lehrer: Josie Cox, her new book is Women Money Power: The Rise and Fall of Economic Equality. Thank you so much for sharing it with us and taking calls from our listeners.

Josie Cox: Thank you so much for having me.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.