More than 60 people were injured and at least 19 people have died after a space heater sparked an enourmous fire in a high-rise apartment building in the Bronx. Charles Jennings, associate professor of Security, Fire and Emergency Management, and director at the Christian Regenhard Center for Emergency Response Studies (RaCERS) at John Jay College of Criminal Justice (CUNY), and Jake Offenhartz, reporter for Gothamist and WNYC, talk about what happened and answer listener questions about fire safety best practices.

They discuss details on who owns the building and what fire safety elements may have been missing and say what can be done on a city policy and individual level to keep New Yorkers safe in similar high-rise buildings.

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. You've no doubt heard about the fire that broke out in a building in the Fordham Heights section of the Bronx yesterday, East 180 first street for people who don't know the area that's near the Grand Concourse north of the Cross Bronx Expressway, south of Fordham road. Not that far after getting off the George Washington bridge, let's say, coming into the Bronx, but a little north of the Cross Bronx Expressway, a little ways in.

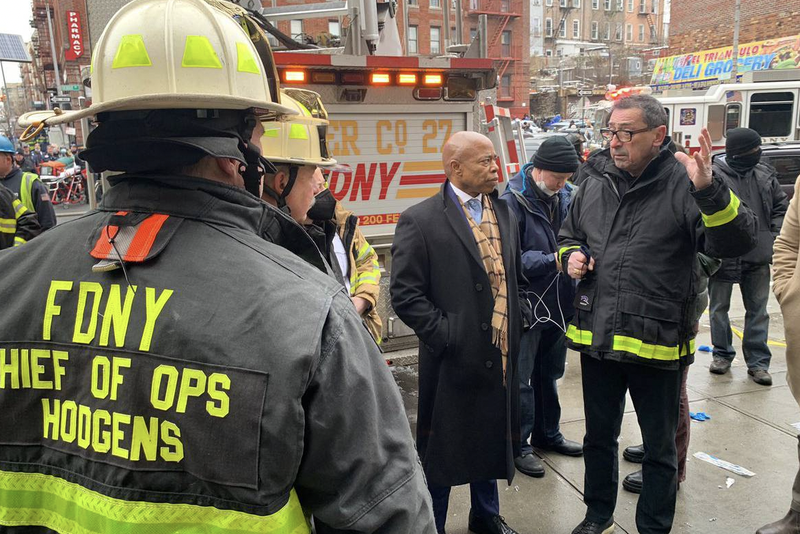

It's being called one of the cities deadliest fires in decades after 19 people, including nine children, were killed. The primary cause of death, in this case, was smoke inhalation. At least that was the immediate cause. Here's fire commissioner, Daniel Nigro.

Daniel Nigro: The door to that apartment, unfortunately, when the residents left was left open, it did not close by itself. The smoke spread throughout the building thus the tremendous loss of life and other people fighting for their lives right now in hospitals all over the Bronx.

Brian Lehrer: FDNY commissioner, Dan Nigro at a press conference yesterday, he said the fire was likely caused by a malfunctioning space heater being used in a duplex apartment in the building. While it's not completely clear at this point, whether this was the case, officials reminded new Yorkers. If you're using a space heater, be sure to plug it directly into the wall outlet, as opposed to using an extension cord. They also reminded of an often discussed fire safety practice that may have prevented fatalities in this case, close the door when leaving a room or an apartment that has a fire.

Between those and other fire safety tips that we may sometimes take for granted, what can we do to prevent tragedies like this in the future? What's happening at a city policy level to ensure large apartment buildings like this are safe for everyone inside and do the landlords bear any of the blame here. This is a building owned, as I understand it by a consortium of corporations.

Here to tell us more are Charles Jennings of Security, Fire, and Emergency Management, Director of the Christian Regenhard Center for Emergency Response Studies at John Jay College of criminal justice. Very long way of saying he's a fire science professor at John Jay plus Gothamist reporter Jake Offenhartz who's been covering the aftermath of the fire in the building it occurred in. Thanks to both of you for coming on this morning, sorry under these circumstances.

Jake Offenhartz: Thank you.

Charles Jennings: Thanks, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: Jake, before we get into policy or safety tips or anything else, could you talk a little bit about the people who died as a result of the fire and some who are fighting for their lives right now, even still, I want to make sure that we're talking about these people as human beings and not as statistics.

Jake Offenhartz: I was at the scene yesterday and as you would imagine, it was really tough. There were people trying to locate their loved ones. There was just a lot of confusion about where people had gone, in terms of what hospitals maybe where they were going to sleep that night if they survived. At this point, we know that there were nine fatalities, nine of whom were children. I've heard that several, if not, the majority of the fatalities were members of the West African immigrant community, which had a big presence in the neighborhood.

There were a lot of mosques around there and this community had moved specifically into this building and this development, it seemed like starting in the '80s, and had really formed a close-knit faith group here. When I was in the red cross-distribution center, which is the middle school next to the building last night and you saw people just sitting on the floor, sobbing, consoling each other, really grieving the loss of their close community members.

Brian Lehrer: Professor Jennings, at the press conference following the fire Mayor Adams brought up the large immigrant population living in this community in general. I'm not sure about the particular building, but I think the mayor believe that that was likely in the particular building. Does fire safety outreach always exists in multiple languages getting to all communities or are there gaps?

Charles Jennings: The FDNY has a fairly well-developed public education operation. They do have multiple languages available. I'm sure, as in all undertakings could they do more? Yes. Could they do more frequently and more aggressive outreach? I would certainly say yes. They do have public education. They do have social media channels to the degree that people are monitoring them. Many times the most at-risk populations are not necessarily in a direct line to get those kinds of messages.

I just want to say with regard to the immigrant issue, I don't want to overplay the immigrant issue in some ways people try to excuse these things and say, "They were recent immigrants." Some implication that they weren't familiar with our procedures or our policies.

In this case, as the reporter pointed out, this is a well-established community in that building. We've had a number of other high-rise building fires where the apartment door does not get closed and these doors are supposed to be self-closing. I think it's an endemic problem. It's not unique, unfortunately, to this fire. Just the consequences here are just staggering though.

Brian Lehrer: One thing Professor Jennings that I was wondering about is how the fire spread from floor to floor. I understand it spread up and down through multiple floors, and this is one of those relatively more modern buildings. At least it's a post-war building that doesn't have fire escapes. It has the stairwell doors that are supposed to prevent just by being closed fire from going from one floor to another, even if an apartment door is left open.

What's your best understanding as to what happened in that respect and are all the other buildings in the city that are supposed to prevent fire spread that way actually safe?

Charles Jennings: Let me distinguish between fire spread and smoke spread and it sounds like a technicality. The code deals with them differently. With regard to fire spread at least and again, my knowledge of this incident is informed by the media report. I don't have any special insights or information on this particular fire, but the fire appears to have been fairly well confined to the duplex of origin. Now there may have been some incidental extension of the fire. The issue was the travel and the spread of smoke.

As you pointed out and as the commissioner points out, rightly so, the primary means of spread of smoke would be via the apartment door into the common hallway. Then from that common hallway into stairwells to the degree that either those doors are not closed or become opened during the fire, as people evacuate, as people try to go up and down those stairways and they're moving around. Ultimately when the fire department arrives, they have to attack the fire from the stairway, that's where they have access to the water supply.

Once they start attacking the fire from a particular stairwell then that stairwell will become filled with smoke. The other mechanism of smoke spread, which I think may have come into play here is if you have a well-developed fire, it develops basically some pressure and the heated products of combustion, the smoke, the toxic gases, and the particulates that constitute smoke are pushed through the building.

If there are cracks in floor assemblies, if there are pipe chases or other means, basically if you can imagine somebody has a cable installed, and so you drill a little hole and do they stop that hole up? In most cases, they don't. That building has been around, I guess it was built in the early 70s. It's been around for some time. Over time those separations between floors and between apartments can get compromised and smoke can penetrate. From the reports, the smoke basically permeated the entire upper part of the building as a result of this fire

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, we can take some phone calls relevant to the fire in the Bronx that has killed at least 19 people. Anybody listening now from that building, anybody listening who knows anybody who was affected by that fire we invite your calls. Anybody else with a question about fire safety as implied by what happened there for fire safety, Professor Charles Jennings from John Jay or Gothamist reporter and WNYC reporter Jake Offenhartz, who's covering the aftermath and has been to the building. 212- 433-WNYC, 212-433-9692 or tweet your question @BrianLehrer.

Jake, who owns this building and do we know if everything was up to code from a fire safety standpoint?

Jake Offenhartz: Yes, good question. The ownership of the building is less than straightforward. It is what's called a Mitchell-Lama affordable housing complex. It's overseen by the state. It gets some federal Section Eight vouchers and it's so that the residents are low to middle income. The ownership is private and it's sold to a group of three investors two years ago. The LIHC investment group, Belveron Partners and Camber Property Group.

I spoke to some residents who were confused about who owned their building, who they're supposed to talk to about issues. They noted that there used to be 24/7 security, but that had disappeared under the new ownership, and because there wasn't 24/7 security, there was this ongoing issue I heard from multiple people that smoke alarms were going off in the building a lot and people just grew to ignore them because there was no one to turn them off, because the security wasn't there. Sometimes they would make calls to FDNY.

We don't have any active violations that are specifically related to fire safety issues. There had been some complaints about lack of heat. There had been complaints about rodents. An elevator was broken. There was some money that was given out a few years ago, state money to make repairs to the building. It's unclear to what extent that happened.

One thing that I don't have a clear answer on right now is how reliable the heat was. We were told that there was an electric heater that caused this problem. Was that because the heat wasn't on? I'm not sure. I spoke to residents who said that for the most part, the heat has been on this winter, but it also has been finicky in the past. That's something we're still looking into.

Brian Lehrer: Professor Jennings, can you elaborate further on the space heater aspect of this first space heater safety, if you use a space heater, but also the possibility that if somebody is using a space heater, it might be because their landlord, isn't providing sufficient heat.

Charles Jennings: Well, taking those backwards, absolutely, it's not definitive, but it's a reasonable conclude if somebody is relying on a space heater that there may indeed be inadequate heat provided to their unit. Of course in a big building like this, that could vary unit by unit, particularly as they're duplexes. It would be hard to generalize that.

With regard to the space heater safety, they are tricky, the newer ones that have been out for some years now have a number of safety features included that normally if they tip over, they automatically shut off but the electrical issue is a perpetual one in New York. Many of these apartments were constructed almost all apartments in New York had been constructed before, "the modern era", of appliances, and anybody goes to their just their bedside. They've got a phone plugged in, and probably a tablet and goodness know what else in addition to the lamp. There may be a shortage of outlets which may have made it more challenging for them to properly use that device.

The other issue, the big one is the three feet clearance on all sides, which I know in many smaller rooms can be challenging, but bedrooms in particular are tough because you've got bedding materials and in proximity they can very easily get on or fall on top of a space heater.

Brian Lehrer: Jake, I read that the building is owned by a group of investors, including Camber Property Group, co-founder Rick Gropper is listed as the building landlord and he happens to be on Eric Adams transition team for housing. Do you know anything about him or this group of corporation that owns the building?

Jake Offenhartz: I don't know much more than that. We saw that Rick Gropper was listed on this transition team. We've reached out to the building owners and they told us that they're devastated by the fire. We know that the other principal here is a man named Andrew Moelis. He has connections to a for-profit affordable housing developer Ron Moelis, the city reported that earlier. I don't know much more about the ownership structure at this point.

Brian Lehrer: Marilyn in Manhattan, you're on WNYC. Hi, Marilyn.

Marilyn: Oh, hello. Can you hear me?

Brian Lehrer: Yes.

Marilyn: Okay. My question is about the major factor in this fire was that the doors between the floors and the stairwell were not closed. I have a question about code. I'm in a loft building, a converted loft building. We have two stairwells and there aren't any doors, it's completely open to every floor. I want to know what is the code about having the stairwells having doors on each floor.

Brian Lehrer: Professor Jennings, can you answer that question?

Charles Jennings: Well, I'm not absolutely certain, that to me is you need doors on stairwells in a multi-storey, and a loft-type building should have stairwell doors or some separation between the floors.

Marilyn: Okay. Do you know how I would find out? I mean, we did get our residential [unintelligible 00:16:25]. They supposedly passed all requirements, but now that I'm hearing about the horrific fire, I'm nervous. I want to find out is our building in fact up to code. Can you advise me on that?

Charles Jennings: Well, the department of buildings or the fire department would have the regulatory responsibility for that. They would be able to advice and I wouldn't want to drill in on the air just because loft buildings they don't have any storeys and all the particulars, so but I would follow-up with them.

Brian Lehrer: Marilyn, good luck. Susan in Manhattan you're on WNYC. Hi Susan.

Susan: Hi. I was the one who originally asked about the heating situation. I have a problem in my apartment and over years, the landlord finally gave me a heater to rectify this. Of course, I'm paying the electricity for that, which is also another issue, but it seems to me that that was the original problem and you're supposed to call 311 when you don't have heat.

The problem is that, number one, you have no idea when the inspector comes, what time of day or what day. If you have heat sporadically, like I did, like I do and perhaps these people and particularly if they don't know who the landlord is because they always ask you, "Who is your landlord? What is his contact number?" I don't know if you're aware of this, but the landlord is contacted first before an inspector comes. If [inaudible 00:18:08] a mouse and cat game, and I'm concerned, not only with that building, but other buildings in poor areas where they don't have, HPD is not doing its job.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you, Susan. Is that the way it works, Professor Jennings? If there's going to be an inspection of a building for things including fire code violations, or if they're up to code, do the landlords get advance notice of that?

Charles Jennings: Normally, the [unintelligible 00:18:40] is not just going to come in because they would need access from the landlord to see mechanical spaces and things like that. I'm not particular familiar with the particulars of heat complaints in terms of how those are enforced.

Brian Lehrer: Yes, and it could be an incentive if you know they're coming to get something there could be a code violation up to code. That's an optimistic interpretation of no-surprise inspections. The fire commissioner yesterday said that the building was potentially built outside the city code because it was by the federal government originally in a federal housing program. Do you have a sense of, in what ways it might be out of code because of that?

Charles Jennings: I haven't had a chance to run that down. I know the 1968 New York city building code changed a lot of requirements with regard to placing what would've been cinder block fire partitions with drywall and then the development of these projects, many of them was by the urban development corporation, New York State Urban Development Corporation may have had a different regulatory regime essentially falling under state control as opposed to city control. It is not inconceivable that there would be some differences between a building built in New York City code and one of these buildings.

Brian Lehrer: A listener asks on Twitter, "Why weren't first responders able to save the people?" Is that an answerable question?

Charles Jennings: The fire department did the best they could. There are just logistical and time requirements to get up the stairs in that building to physically move through the building to remove people. It's extremely labor-intensive, and so with the numbers of people that were impacted by the spread of smoke, and I don't know yet how many of those were in common areas, how many were taking shelter in their apartments, it does not take long for people to be overcome by smoke.

The amount of time to remove somebody from that environment, particularly where you have multiple floors that are contaminated with smoke, it's not like you have a fire floor, you get them out of that floor, you take them down a floor below and it's clear, if you're on the 10th or the 15th floor, you've got to come down 10 storeys of heavy smoke to get out of the building. It's a very challenging undertaking and very labor-intensive.

Brian Lehrer: Jake, we have a minute left. Officials and volunteers set up a shelter at a nearby school last night, but as that's an act of school, I understand they had to set up at another site. Do you know where people who lost their homes are now and what kind of relief they're getting and if there's any information for listeners who might want to help them in any way?

Jake Offenhartz: Yes, there are a lot of people who are scattered around different hotels right now, is my understanding. Some people were allowed back in the building to get some medicine last night I heard. The building is considered structurally sound, but for the most part, people are living either with friends or family or in hotel rooms right now. Anyone who needs support, and I imagine people who may be able to lend support was urged to reach out to the Red Cross. They're at 1 800 Red Cross. There's also the Islamic Cultural Center of the Bronx. They've been serving as a hub for a lot of the victims here. I believe that they're collecting donations and food for the victims, and so it's kind of a fluid situation. People are still moving around from what I could tell and not everyone has been able to get back up.

Brian Lehrer: WNYC and Gothamist's Jake Offenhartz, fire science Professor Charles Jennings from John Jay, thank you both.

Jake Offenhartz: Thanks, Brian.

Charles Jennings: Thank you.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.